A Guide to the Braille Writing System and Its Use

Author: Thomas C. Weiss

Published: 2009/06/24 - Updated: 2025/10/13

Publication Type: Informative

Category Topic: Disability Visual Aids - Academic Publications

Page Content: Synopsis - Introduction - Main - Insights, Updates

Synopsis: This informative resource provides a comprehensive overview of Braille, the tactile reading and writing system invented by French educator Louis Braille in the 19th century. The article explains how Braille works through raised dot patterns arranged in cells, details the three grades of Braille used for different purposes, and demonstrates the English Braille alphabet with visual examples. What makes this information particularly authoritative and useful is its thorough coverage of practical applications—from everyday items like playing cards and thermometers to complex subjects including mathematics, music notation, and legal documents—along with specific details about volunteer training standards set by the Braille Authority of North America and the certification process required for transcribers.

The resource serves people with visual impairments, educators, family members, and community volunteers by explaining not only the technical aspects of Braille but also its profound impact on literacy, independence, and access to information, making it clear that Braille functions as the equivalent of print for those with vision loss, enabling everything from education and employment to cultural enrichment and the management of daily adult responsibilities - Disabled World (DW).

Defining Braille

- Braille

Braille is a tactile writing system used by people who are visually impaired, including people who are blind, deafblind or who have low vision. Braille is named after its creator, Louis Braille, a Frenchman who lost his sight as a result of a childhood accident. Teachers, parents, and others who are not visually impaired ordinarily read braille with their eyes. Braille is not a language. Rather, it is a code by which many languages - such as English, Spanish, Arabic, Chinese, and dozens of others - may be written and read. Braille characters are formed using a combination of six raised dots arranged in a 3 × 2 matrix, called the braille cell. The number and arrangement of these dots distinguishes one character from another. In addition to braille text (letters, punctuation, contractions), it is also possible to create embossed illustrations and graphs, with the lines either solid or made of series of dots, arrows, and bullets that are larger than braille dots.

Introduction

Braille is a tactile system of raised dots that represent letters of the alphabet which can be used by persons with vision impairment. In order to read braille, a person gently glides their fingers over paper which has been embossed with braille code. For note taking purposes, a person uses a pointed instrument to punch dots into paper that is held in a metal slate. The punched holes appear as dots that are readable on the other side of the paper. Braille is, to a person who experiences vision loss, what printed words are to persons who are sighted. Braille provides access to both information and contact with the outside world.

Main Content

The Braille alphabet is the building block for language skills; it is a means for teaching spelling to children who have vision loss, as well as the most direct means of contact through written thoughts of others. Books written in Braille are available in every subject area, from modern day fiction writings all the way through mathematics, law, and music. Braille is being used for everything from labeling of objects to the taking of notes. Braille adapted devices to include playing cards, watches, games, and even thermometers are examples of just some of the many both recreational and practical uses of braille in the world today.

Braille was invented centuries ago by Louis Braille (1809-1852). Louis Braille was a French teacher of persons who were blind. He created a system of patterns of raised dots that are arranged in cells of up to six dots in a 3 X 2 configuration. Each cell represents a letter, number, or punctuation mark; some letter combinations or words that are used more frequently have their own cell patterns.

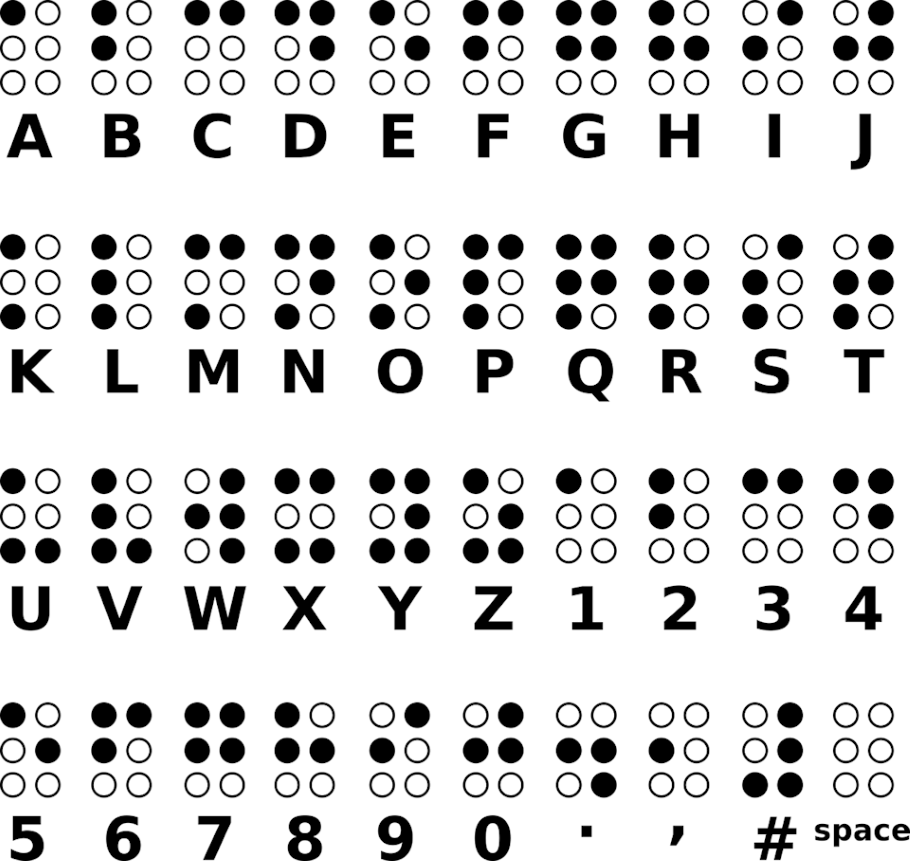

English Alphabet in Braille

Braille Versions

There are various versions of Braille in existence today:

- Grade 1 Braille : Consists of the 26 standard letters of the alphabet and punctuation, and is only used by people who are first starting to read Braille.

- Grade 2 Braille : Consists of the 26 standard letters of the alphabet, punctuation, as well as contractions. The contractions are used to save space because a Braille page cannot fit as much text as a standard printed page. Books, signs in public places, menus, and most other Braille materials are written in Grade 2 Braille.

- Grade 3 Braille : Only used in personal letters, diaries, and notes. Grade 3 Braille is a kind of shorthand, with entire words shortened to a few letters.

In the modern world, Braille has been adapted to write in a number of different languages, to include Chinese. Braille is also being used for both mathematical and musical notation. The invention of Braille has led to new ways to assist persons with disabilities such as ADA ramps, also referred to as, 'Braille for feet.'

English Letters, Numbers, and Punctuation Converted to Braille: Conversion table includes the English alphabet in Braille, HTML, Unicode, UTF-8, Hex, and Decimal including numbers 0-9, and common punctuation marks.

Through the use of Braille, persons who are visually impaired have the ability to both review and study the written word. They have the ability to become aware of various conventions to include spelling, punctuation, paragraphing, and footnotes. More than anything, persons who are visually impaired can access a wide-variety of reading materials, from educational and recreational written material, to practical manuals. They can access regulations, contracts, directories, insurance policies, cookbooks, and appliance instructions, for example - all of which are important parts of daily adult life. Through the use of Braille, visually impaired persons have the ability to pursue both cultural enrichment and hobbies through board and card games, hymnals, and musical scores.

As with any new language, learning Braille takes a certain amount of time and practice to learn.

Braille is commonly taught to persons who are visually impaired as part of a vision loss program. Braille is also taught through schools within communities. Sighted volunteers transcribe printed texts into Braille.

Volunteers pursue approximately eight months of training before becoming certified Braillists. The training they complete conforms to standards which are set in cooperation with the Braille Authority of North America. Additional training is required before a person can braille educational materials for students, or before they may specialize in transcription of music into braille. The average reading speed for a person using Braille is about one-hundred and twenty-five words per minute; although speeds of up to two-hundred words per minute are possible.

All around America, dedicated volunteers work in communities produce braille materials for persons with visual impairments.

Volunteers produce materials which serve to supplement both magazines and books that are produced in quantities by nonprofit organizations for the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped (NLS) of the Library of Congress. All of these volunteers have completed a lengthy and detailed course on Braille transcription that results in an award by the Library of Congress and a Certificate of Proficiency in the appropriate Braille code. The activities these volunteers pursue include transcription of printed material into Braille, binding Braille books, and duplication of copies. Volunteers provide persons with vision impairments in their communities with essential materials that might otherwise be unavailable.

The services these volunteers provide are used by local school systems, the NLS, state departments, and the nationwide network of cooperating libraries that distributes both magazines and books through the NLS program. The National Braille Association (NBA) is an organization of volunteers that provides both students and other people with Braille materials they request. Becoming a Braille volunteer requires intellectual curiosity, training, patience, meticulousness, and the ability to work under pressure. It also requires the ability to both understand and follow directions. The rewards of being a Braille volunteer include an immense sense of accomplishment, as well as learning a completely new system of both reading and writing.

Insights, Analysis, and Developments

Editorial Note: The enduring relevance of Braille in our increasingly digital age speaks to a fundamental truth about accessibility: technology may evolve, but the human need for direct, independent access to written language remains constant. While audio formats and screen readers offer valuable alternatives, Braille provides something irreplaceable—the ability to engage with spelling, punctuation, and the structural nuances of language that form the foundation of true literacy. The dedication of volunteers who spend eight months training to become certified transcribers, and the continued expansion of Braille into new languages and specialized fields, demonstrates that this 19th-century innovation remains as vital today as when Louis Braille first conceived it, serving not merely as an accommodation but as a gateway to full participation in literate society - Disabled World (DW). Author Credentials: Thomas C. Weiss is a researcher and editor for Disabled World. Thomas attended college and university courses earning a Masters, Bachelors and two Associate degrees, as well as pursing Disability Studies. As a CNA Thomas has providing care for people with all forms of disabilities. Explore Thomas' complete biography for comprehensive insights into his background, expertise, and accomplishments.

Author Credentials: Thomas C. Weiss is a researcher and editor for Disabled World. Thomas attended college and university courses earning a Masters, Bachelors and two Associate degrees, as well as pursing Disability Studies. As a CNA Thomas has providing care for people with all forms of disabilities. Explore Thomas' complete biography for comprehensive insights into his background, expertise, and accomplishments.