Rethinking People-First Language: A Critical View on Disability Terminology

Author: Jenny Blackler

Published: 2015/01/13 - Updated: 2025/12/30

Publication Type: Informative

Category Topic: Blogs - Stories - Related Publications

Page Content: Synopsis - Introduction - Main - Insights, Updates

Synopsis: This article presents a critical perspective on people-first language, arguing that while intended to promote dignity and equality for individuals with disabilities, it often results in awkward, repetitive phrasing and fails to achieve its intended goals. Drawing on both personal experience and the views of disability advocates, the author contends that changing language does not fundamentally alter societal attitudes or reduce stigma, as connotations and biases persist regardless of terminology. The article highlights how people-first language can inadvertently create division by alienating those unfamiliar with evolving linguistic norms, sometimes leading to the unfair judgment of well-intentioned individuals.

This information is particularly useful for professionals, caregivers, and advocates in the disability community, as it encourages critical reflection on the effectiveness of language-based initiatives and suggests that genuine change is more likely to result from building relationships and fostering understanding rather than focusing solely on prescribed terminology. The authority of the article lies in its thoughtful analysis, grounded in both lived experience and reference to established critiques within the disability rights movement - Disabled World (DW).

Introduction

I've been working with people with disabilities for years now. This is not my original background, this is not what I went to school for. In fact, I really hadn't had too much experience with persons with disabilities until I started working for my current company. And contrary to how people often treat that, I'm not sure it's a bad thing. Coming into an industry where most people have spent years of their lives, an industry that has created its own sub-culture, has given me some strengths: namely, fresh eyes. By seeing things as an outsider and glimpsing a foreign world has given me the eyes of a recent immigrant in a distant culture: I tend to notice things, good and bad, that others probably have never thought of. And with any foreign culture, there will inherently be certain aspects that an outsider can only shake their head at, smirking at the thought of how this came to be and wondering why everyone else seems to be so obedient and accepting of this strange custom.

And the strange custom I am talking about in this case is the concept of people first language. Seeing this as an outsider, I am of the admittedly radically heretical opinion that people first language is actually a waste of time, unable to prevail in the goal it sets out to do by its very nature, and further, that people first language actually sets us farther back in the goals of integration and equality for people with disabilities. And as such, this idea should be abdicated and resources moved to support different ideas that are better suited to bring about change.

I can only imagine your disdain and shock at my words right now. After all, people first language is a hallmark of this industry, a great source of pride for those who have spent years fighting for this idea. And while I can appreciate and respect those who have tried to do so, this idea represents to me the two problems I have mentioned. So let's look at those...

Main Content

So What is This So Called "People First Language"?

Well, it's a type of linguistic prescription in English, aiming to avoid perceived and subconscious dehumanization when discussing people with disabilities, as such forming an aspect of disability etiquette. The term people-first language first appears in 1988 as recommended by advocacy groups in the United States. The basic idea is to impose a sentence structure that names the person first and the condition second, for example "people with disabilities" rather than "disabled people" or "disabled", in order to emphasize that "they are people first". Because English syntax normally places adjectives before nouns, it becomes necessary to insert relative clauses, replacing, e.g., "asthmatic person" with "a person who has asthma." Furthermore, the use of to be is deprecated in favor of using to have. The speaker is thus expected to internalize the idea of a disability as a secondary attribute, not a characteristic of a person's identity. Critics of this rationale point out that separating the "person" from the "trait" implies that the trait is inherently bad or "less than", and thus dehumanizes people with disabilities.

Critics have objected that people-first language is awkward, repetitive and makes for tiresome writing and reading. C. Edwin Vaughan, a sociologist and longtime activist for the blind, argues that since "in common usage positive pronouns usually precede nouns", "the awkwardness of the preferred language focuses on the disability in a new and potentially negative way". Thus, according to Vaughan, it only serves to "focus on disability in an ungainly new way" and "calls attention to a person as having some type of 'marred identity'" in terms of Erving Goffman's theory of identity.

The National Federation of the Blind adopted a resolution in 1993 condemning politically correct language. The resolution dismissed the notion that "the word 'person' must invariably precede the word 'blind' to emphasize the fact that a blind person is first and foremost a person" as "totally unacceptable and pernicious" and resulting in the exact opposite of its purported aim, since "it is overly defensive, implies shame instead of true equality, and portrays the blind as touchy and belligerent".

Keep in mind that the disability rights movement and its thinking is almost unknown outside the movement itself!

It's a Waste of Time

People first language inherently cannot accomplish what it is trying to accomplish.

It's not that people first language could be better and more effective if marketed differently, or took a different approach, or some other such change.

The problem is it just can't do what it's trying to do. Period. People first language is, at its core, based on a distinctively odd, Orwellian philosophy which does not reflect reality: that we can change our thoughts on an object by changing the language we use to describe it. We, as people, often want to believe this but language doesn't work like that: it's descriptive, not prescriptive.

Changing language may help to soften a blow ever so slightly (as in saying some "passed away" rather than "dead") or make subtle changes of that nature, but it doesn't actually change how a person feels about something overall. Language doesn't work like that. It can't. And even when we do manage to make substantive changes to the denotation of a word, we simply cannot change the connotation. That is intrinsic to each and every one of us and no amount of forcing someone to use a correct term can erase a derision or sneer that accompanies it.

And we are already seeing the fruitlessness of this labor.

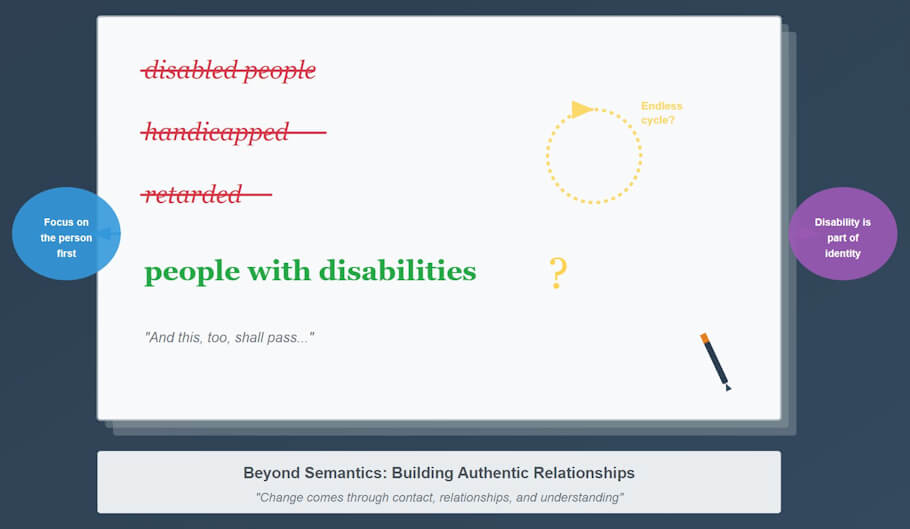

Terms come and go. Why? Because after a point in time, we realize the term did not accomplish its goal, so we set off to find a replacement. Rather than reaching the conclusion that the very concept of using linguistic mechanisms to change thought and perception is not effective, we just assume the word is the problem. Years ago "retarded" was the proper word. But that was deemed offensive. Then "handicapped." Same result. "Disabled" Gone. Now it's "person with a disability." And this, too, shall pass. My 2 year old son, in 30 years when he is about my age, will talk in horror with his friend about how his dad actually used to use the phrase "person with a disability," and his friend will nod understandingly and say it's ok, his dad still does. That's how this works. The good, pure, holy expression of today is the offensive vulgarity of tomorrow. Because we don't recognize the word isn't the problem, so our immortal, endless, Holy-Grail-of-a-quest continues. And will continue ad infinitum.

People First Language Actually Makes the Situation Worse, Not Better - How?

By causing us to demonize people who should never be demonized!

People whose only sin is to be innocently unaware that a particular subculture within America has changed its rules are found to be offensive, and we in this industry immediately despise them. I cannot tell you how many times I have been at a seminar, and the person speaking will be talking about an experience with a manager at a business or some other similar situation, and the speaker will put their hands on their hips, look at the audience and say with disgust, "And do you know what the manager said? She said, 'Handicapped people often make great employees." And the crowd will gasp at the word "handicapped." They will shake their heads, and throw their hands into the air, crying out to god at this offense, deemed to be merely half an inch shy of out-and-out genocide at people with disabilities. They are completely offended, not knowing that context often was meant to be a compliment and no offense was ever intended. Napolean Bonaparte once said, "never ascribe to malice that which can adequately be explained by incompetence." And so it is here.

I know a 75 year old man who lives in my hometown but was a farmer in South Dakota most of his life.

He still uses the phrase "retarded." And I fear I'm about the only one in this industry not offended by that word when he says it. Why? Because I know he doesn't mean anything by it. Again, he's a 75 year old farmer from South Dakota. In his day, "retarded" was the word. It wasn't offensive, it was the word of choice just as "person with a disability" is today. And he has no idea that his word is now offensive. But he's a good guy. I know him well, and he's a very gentle, compassionate, old man. I get a number of leads from him. He'll say things like, "You know, I talked to ol' Jim at the hardware store today about having a retarded person come work for him. He said you could talk to him a little bit about it if you want." Here's a man doing my work for me, opening up doors for our clients because he cares. But most social workers would dismiss him and find him offensive because he has no idea the rules have changed around him in regards to his vocabulary.

And that's the danger of people first language: changing the rules arbitrarily on a whim only leads others to fail by lack of knowledge that the rules had changed. And isn't there a horrible, awful irony in that? Isn't the very point of people first language to try and get people to not be judgmental when they meet a person with a disability, rather than taking the time to get to know the person? And yet, when a person doesn't get the language exactly right, aren't they judged by social workers and dismissed immediately in exactly the manner people first language is trying to avoid

My point in all of this writing is to say that there is no doubt your heart is pure in pushing people first language.

There is no doubt you have the best intentions.

There is no doubt you are earnestly seeking to create a better world for people with disabilities.

But I'm not sure this is the way.

Life is about opportunity costs: every moment you spend pursuing A is time not spent pursing B or C or D. So we need to always weigh our actions by other things we could be pursuing, not simply what we are pursuing in and of itself. And my argument is that there are far better pursuits that would help people with disabilities. Change comes about through contact, through relationships, through understanding that comes from experience. That is what changes the world, changes hearts, and changes minds. Not through mechanical means like attempting to alter semantics. If you want to change the world for people with disabilities, seek integration, seek relationship building. That's a far better use of time and resources than an Orwellian idea that leads to the demonizing of people who may otherwise have been viewed as friends and allies - Seek to build relationships instead.

As one writer eloquently stated:

"...it's incredibly rude to think that you get to be the one who decides how I get to talk about myself. I'm not telling you how to talk about who you are - show me the same courtesy."