Ötzi, the 5,000 Year Old Iceman

Author: Georgia Institute of Technology

Published: 2017/08/23 - Updated: 2025/12/06

Publication Details: Peer-Reviewed, Anthropology News

Category Topic: Anthropology - Related Publications

Page Content: Synopsis - Introduction - Main - Insights, Updates

Synopsis: This peer-reviewed research examines how genetic disease risks have evolved over millennia by analyzing ancient DNA, including that of Ötzi, the 5,000-year-old Iceman discovered in the Alps in 1991. Conducted by researchers at Georgia Tech and published in the journal Human Biology, the study found that over the long term, evolution has effectively reduced the frequency of disease-promoting genetic variants while increasing protective ones, meaning most ancient populations carried significantly higher genetic risks for cardiovascular disease and other conditions than we do today.

However, the research also suggests a troubling reversal over the past 500 to 1,000 years, with modern humans showing worse genetic underpinnings for psychiatric disorders like depression and bipolar disorder compared to our ancient ancestors. For people interested in understanding human health and disability from an evolutionary perspective - whether they have disabilities themselves or care about the medical future of populations - this research offers valuable insights into how genetic disease susceptibility has shifted across human history and what that might mean for contemporary and future healthcare challenges - Disabled World (DW).

- Definition: Ötzi

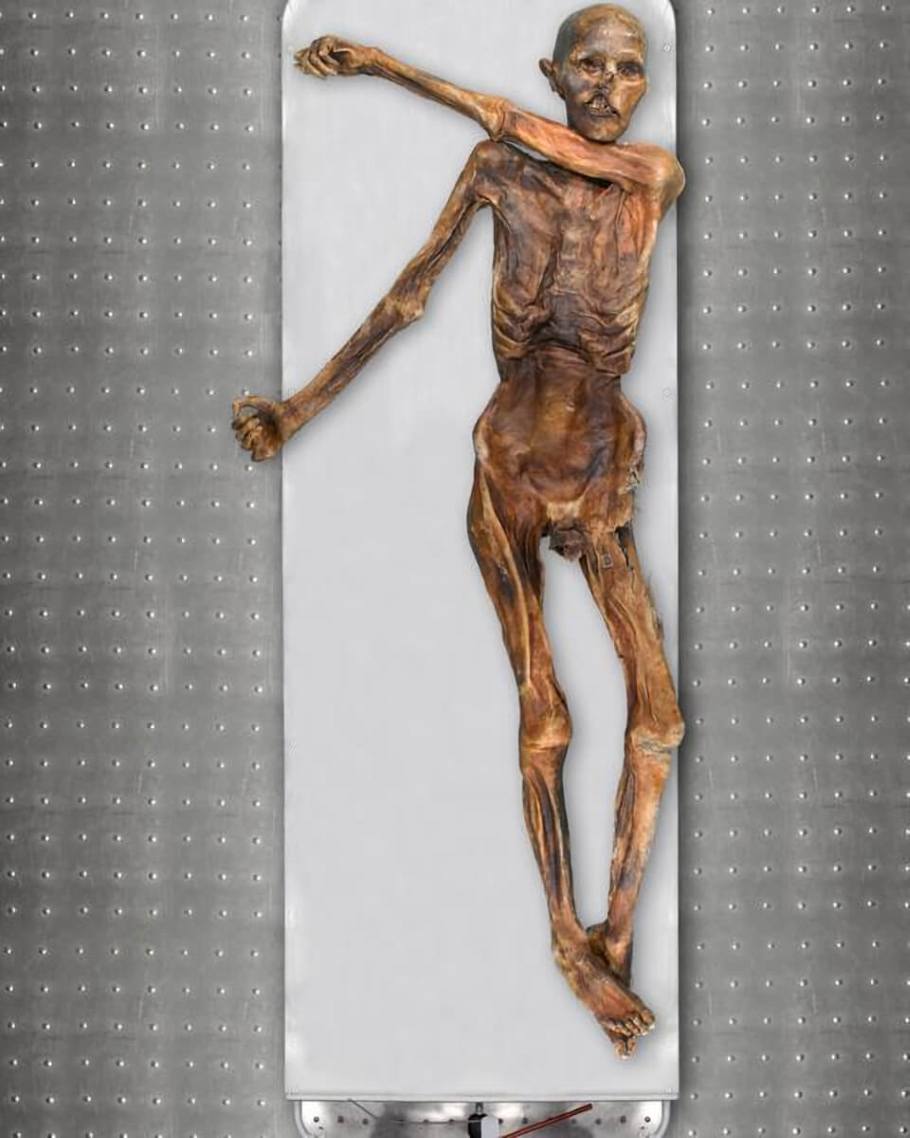

Ötzi, also called the Iceman, is the natural mummy of a man who lived between 3350 and 3105 BC. Ötzi was found on 19th September 1991 by two German tourists, at an elevation of 3,210 m (10,530 ft.) on the east ridge of the Fineilspitze in the Ötztal Alps on the Austrian-Italian border, near Similaun mountain and the Tisenjoch pass. He is Europe's oldest known natural human mummy, offering an unprecedented view of Chalcolithic (Copper Age) Europeans. Because of the presence of an arrowhead embedded in his left shoulder and various other wounds, researchers believe Ötzi was murdered. By the most recent estimates, at the time of his death, Ötzi was 160 cm (5 ft. 3 in) tall, weighed about 50 kg (110 lb.), and was about 45 years of age. His remains and personal belongings are on exhibit at the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano, South Tyrol, Italy.

Introduction

Ancient DNA Reveals Modern Humans Have Worse Genetics

Had an arrow in his back not felled the legendary Iceman some 5,300 years ago, he would have dropped dead from a heart attack. Written in the DNA of his remains was a propensity for cardiovascular disease.

Heart problems were much more common in the genes of our ancient ancestors than in ours today, according to a new study by the Georgia Institute of Technology, which computationally compared genetic disease factors in modern humans with those of people through the millennia.

Overall, the news from the study is good. Evolution appears, through the ages, to have weeded out genetic influences that promote disease while promulgating influences that protect from disease.

Main Content

Evolutionary Double-take

But for us modern folks, there's also a hint of bad news.

That generally healthy trend might have reversed in the last 500 to 1,000 years, meaning that, except for cardiovascular ailments, disease risks in our genes may be rising. For mental health, our genetic underpinnings looked especially worse than those of our ancient forebears.

Though the long-term positive trend looks obvious in the data, it's too early to tell if the initial impression of a shorter-term reversal will hold. Further research in this brand-new field could dismiss it.

"That could well happen," said principal investigator Joe Lachance, an assistant professor in Georgia Tech's School of Biological Sciences. "But it was still perplexing to see many of our ancestors' genomes looking considerably healthier than ours. That wasn't expected."

Lachance, former postdoctoral assistant Ali Berens, and undergraduate Taylor Cooper published their results in the journal Human Biology. They hope that by better understanding our evolutionary history, researchers will someday be able to project future human populations' genomic health forward, as well as perhaps their medical needs.

Dismal Distant Past

Despite what may be a striking, recent negative trend, through the millennia, genetic risks to health appear to have diminished, according to the study's main finding. "That was to be expected because larger populations are better able to purge disease-causing genetic variants," Lachance said.

The researchers scoured DNA records covering thousands of years of human remains along with those of our distant evolutionary cousins, such as Neanderthals, for genetic locations, or "loci," associated with common diseases.

"We looked at heart disease, digestive problems, dental health, muscle disorders, psychiatric issues, and some other traits," Cooper said.

After determining that they could computationally compare 3,180 disease loci common to ancient and modern humans, the researchers checked for genetic variants, or "alleles," associated with the likelihood of those diseases or associated with the protection from them. Nine millennia ago, the genetic underpinnings of the diseases looked dismal.

"Humans way back then, and Neanderthals and Denisovans - they're our distant evolutionary cousins - appear to have had many more alleles that promoted disease than we do," Lachance said. "The genetic risks for cardiovascular disease were particularly troubling in the past."

Crumbling Health Genetics?

As millennia marched on, the study's results showed that overall genetic health foundations improved. The frequency of disease-related alleles dropped, while protective alleles rose steadily.

Then again, there's that nagging initial impression in the study's data that things may have gone off track for a few centuries now.

"Our genetic risk was on a downward trend, but in the last 500 or 1,000 years, our lifestyles and environments changed," Lachance said.

This is speculation, but perhaps better food, shelter, clothing, and medicine have made humans less susceptible to disease alleles, so having them in our DNA is no longer as likely to kill us before we reproduce and pass them on.

A Grain of Data Salt

Also, the betterment over millennia in genetic health underpinnings seen in the analysis of select genes from 147 ancestors stands out so clearly that the researchers have had to wonder if the reversal in pattern in recent centuries, which seems so inconsistent with that long-term trend, is not perhaps a coincidence in the initial data set. The scientists would like to analyze more data sets to feel more confident about the apparent reversal.

"We'd like to see more studies done on samples taken from humans who lived from 400 years ago to now," Cooper said.

They would also like to do more research on positioning the genetic health of ancients relative to modern humans.

"We may be overestimating the genetic health of previous hominins (humans and evolutionary cousins including Neanderthals)," Lachance said, "and we may need to shift estimates of hereditary disease risks for them over, which would mean they all had a lot worse health than we currently think."

Until then, the researchers are taking the apparent slump in the genetic bedrock of health in recent centuries with a grain of salt. But that does not change the main observation.

"The trend shows clear long-term reduction over millennia in ancient genetic health risks," said Berens, a former postdoctoral assistant. Viewed in graphs, the improvement is eye-popping.

More Psychiatric Disorders

If the initial finding on the reversal does eventually hold up, it will mean that people who lived in the window of time from 2,000 to 6,000 years ago appear to have had, on the whole, DNA less prone to promoting disease than we do today, particularly for mental health. We moderns racked up much worse genetic likelihoods for depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia.

"We did look genetically better on average for cardiovascular and dental health," Lachance said. "But every time we examined, ancient individuals looked healthier for psychiatric disorders, and we looked worse."

Add to that a higher potential for migraines.

The Iceman Cometh

Drilling down in the data leads to individual genetic health profiles of famous ancients like the Altai Neanderthal, the Denisovan, and "Ötzi," the Iceman. Ötzi, like us, was Homo sapiens.

Along with his dicey heart, the Iceman probably contended with lactose intolerance and allergies. Their propensity was also written in his DNA, but so was a likelihood for strapping muscles and enviable levelheadedness, making him a potentially formidable hunter or warrior.

With his bow, recovered near his corpse on a high mountain pass, Ötzi could have easily slain prey or foe at 100 paces. But the bow was unfinished and unstrung one fateful day around 3,300 B.C., leaving the Iceman with little defense against the enemy archer who punctured an artery near his left shoulder blade.

The Iceman probably bled to death within minutes. Eventually, snow entombed him, and he lay frozen in the ice until a summer glacier melt in 1991 re-exposed him to view. Two German hikers came upon his mummified corpse that September on a ridge above Austria's Ötztal valley, which gave the popular press fodder to nickname him "Ötzi."

DNA Tatters

The near ideal condition of his remains, including genetic ones, has proven a treasure trove for scientific study. But Ötzi is an extraordinary exception.

Usually, flesh-bare, dry bones or fragments are all that is left of ancient hominins or even just people who died a century ago. "Ancient DNA samples may not contain complete genomic information, and that can limit comparison possibilities, so we have to rely on mathematical models to account for the gaps," Berens said.

Collecting and analyzing more ancient DNA samples will require vigorous effort by researchers across disciplines. But added data will give scientists a better idea of where the genetic underpinnings of human health came from and where they're headed for our great-grandchildren.

* "Caveman" is a misnomer that stems from human remains and other artifacts being found in caves because they have been better preserved there through the centuries. Strong evidence points to early humans and our evolutionary cousins living mostly in open spaces.

16th August 2023: Ötzi: Dark Skin, Bald Head, Anatolian Ancestry

By Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology

The genetic makeup of most present-day Europeans has resulted mainly from the admixture of three ancestral groups: western hunter-gatherers gradually merged with early farmers who migrated from Anatolia about 8,000 years ago and who were later on joined by Steppe Herders from Eastern Europe, approximately 4,900 years ago.

The initial analysis of the Iceman's genome revealed genetic traces of these Steppe Herders. However, the refined new results no longer support this finding. The reason for the inaccuracy: the original sample had been contaminated with modern DNA. Since that first study, not only have sequencing technologies advanced enormously, but many more genomes of other prehistoric Europeans have been fully decoded, often from skeletal finds. This has made it possible to compare Ötzi's genetic code with his contemporaries. The result: among the hundreds of early European people who lived at the same time as Ötzi and whose genomes are now available, Ötzi's genome has more ancestry in common with early Anatolian farmers than any of his European counterparts.

Ötzi's Ancestry and Appearance

The research team concludes that the Iceman came from a relatively isolated population that had very little contact with other European groups.

"We were very surprised to find no traces of Eastern European Steppe Herders in the most recent analysis of the Iceman genome; the proportion of hunter-gatherer genes in Ötzi's genome is also very low. Genetically, his ancestors seem to have arrived directly from Anatolia without mixing with hunter gatherer groups," explains Johannes Krause, head of the Department of Archaeogenetics at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, and co-author of the study.

The study also yielded new results about Ötzi's appearance. His skin type, already determined in the first genome analysis to be Mediterranean-European, was even darker than previously thought.

"It's the darkest skin tone that has been recorded in contemporary European individuals," explains anthropologist Albert Zink, study co-author and head of the Eurac Research Institute for Mummy Studies in Bolzano: "It was previously thought that the mummy's skin had darkened during its preservation in the ice, but presumably what we see now is actually largely Ötzi's original skin color. Knowing this, of course, is also important for the proper conervation of the mummy."

Our previous image of Ötzi is also incorrect regarding his hair: as a mature man, he most likely no longer had long, thick hair on his head, but at most a sparse crown of hair. His genes, in fact, show a predisposition to baldness.

"This is a relatively clear result and could also explain why almost no hair was found on the mummy," says Zink.

Genes presenting an increased risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes were also found in Ötzi's genome, however, these factors probably did not come into play thanks to his healthy lifestyle.

Insights, Analysis, and Developments

Editorial Note: The journey of Ötzi from a forgotten mountain corpse to a subject of cutting-edge genomic research reminds us that understanding disability and disease is ultimately about understanding ourselves - where we've been, what we've inherited, and what we face ahead. While Ötzi died from a well-placed arrow 5,300 years ago, we now know he carried genetic vulnerabilities to heart disease that persist in many of us today, alongside his genes for strength and resilience. The Iceman's frozen remains offer more than a window into ancient history; they challenge our assumptions about progress and force us to reckon with the possibility that our modern world, for all its medical advances, may have inadvertently created new genetic vulnerabilities that his ancestors never experienced - Disabled World (DW).Attribution/Source(s): This peer reviewed publication was selected for publishing by the editors of Disabled World (DW) due to its relevance to the disability community. Originally authored by Georgia Institute of Technology and published on 2017/08/23, this content may have been edited for style, clarity, or brevity.