Why Humans Remember Emotional Events Better

Author: Columbia University School of Engineering and Applied Science

Published: 2023/01/19

Peer Reviewed Publication: Yes

Category Topic: Human Brain - Related Publications

Page Content: Synopsis - Introduction - Main

Synopsis: Neuroscientists identify a specific neural mechanism in the human brain that tags information with emotional associations for enhanced memory. It's easier to remember emotional events, like your child's birth, than other events from around the same time.

Introduction

Neuronal Activity in the Human Amygdala and Hippocampus Enhances Emotional Memory Encoding

Most people clearly remember emotional events, like their wedding day, but researchers need to find out how the human brain prioritizes emotional events in memory. In a study published January 16, 2023, by Nature Human Behaviour, Joshua Jacobs, associate professor of biomedical engineering at Columbia Engineering, and his team identified a specific neural mechanism in the human brain that tags information with emotional associations for enhanced memory. The team demonstrated that high-frequency brain waves in the amygdala, a hub for emotional processes, and the hippocampus, a hub for memory processes, are critical to enhancing memory for emotional stimuli. Disruptions to this neural mechanism, brought on either by electrical brain stimulation or depression, impair memory specifically for emotional stimuli.

Main Content

Rising Prevalence of Memory Disorders

The rising prevalence of memory disorders such as dementia has highlighted the damaging effects that memory loss has on individuals and society. Disorders such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can also feature imbalanced memory processes and have become increasingly prevalent during the COVID-19 pandemic. Understanding how the brain naturally regulates what information gets prioritized for storage and what fades away could provide critical insight for developing new therapeutic approaches to strengthening memory for those at risk of memory loss or normalizing memory processes in those at risk of dysregulation.

"It's easier to remember emotional events, like the birth of your child, than other events from around the same time," says Salman E. Qasim, lead author of the study, who started this project during his Ph.D. in Jacobs' lab at Columbia Engineering. "The brain has a natural mechanism for strengthening certain memories, and we wanted to identify it."

The Difficulty of Studying Neural Mechanisms in Humans

Most investigations into neural mechanisms occur in animals such as rats because such studies require direct access to the brain to record brain activity and perform experiments that demonstrate causality, such as careful disruption of neural circuits. But it is difficult to observe or characterize a complex cognitive phenomenon like emotional memory enhancement in animal studies.

To study this process directly in humans. Qasim and Jacobs analyzed data from memory experiments conducted with epilepsy patients undergoing direct, intracranial brain recording for seizure localization and treatment. During these recordings, epilepsy patients memorized lists of words while the electrodes placed in their hippocampus and amygdala recorded the brain's electrical activity.

Studying Brain-Wave Patterns of Emotional Words

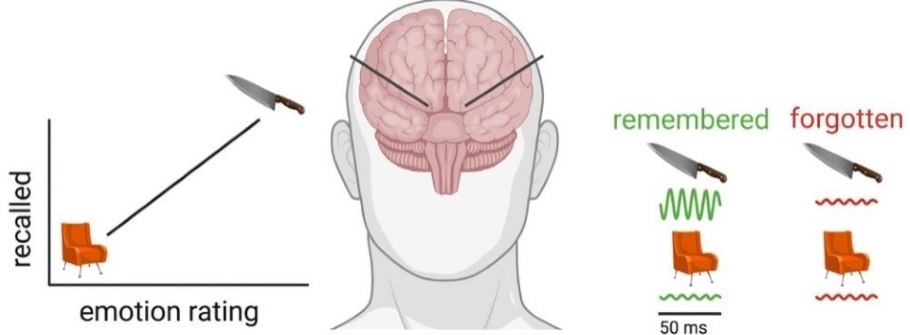

By systematically characterizing the emotional associations of each word using crowd-sourced emotion ratings, Qasim found that participants remembered more expressive words, such as "dog" or "knife," better than more neutral words, such as "chair." When looking at the associated brain activity, the researchers noted that high-frequency neural activity (30-128 Hz) would become more prevalent in the amygdala-hippocampal circuit whenever participants successfully remembered emotional words. This pattern was absent when participants remembered more neutral words or failed to remember a word altogether. The researchers analyzed this pattern across a large data set of 147 patients and found a clear link between participants' enhanced memory for emotional words and the prevalence in their brains of high-frequency brain waves across the amygdala-hippocampal circuit.

"Finding this pattern of brain activity linking emotions and memory was very exciting to us because prior research has shown how important high-frequency activity in the hippocampus is to non-emotional memory," said Jacobs. "It immediately cued us to think about the more general, causal implications-if we elicit high-frequency activity in this circuit, using therapeutic interventions, will we be able to strengthen memories at will?"

Electrical Stimulation Disrupts Memory for Emotional Words

To establish whether this high-frequency activity reflected a causal mechanism, Jacobs and his team formulated a unique approach to replicate the kind of experimental disruptions typically reserved for animal research. First, they analyzed a subset of these patients who had performed the memory task. At the same time, direct electrical stimulation was applied to the hippocampus, for half of the participants had to memorize words. They found that electrical stimulation, which has a mixed history of either benefiting or diminishing memory depending on its usage, clearly and consistently impaired memory, specifically for emotional words.

Uma Mohan, another Ph.D. student in Jacobs' lab at the time and co-author of the paper, noted that this stimulation also diminished high-frequency activity in the hippocampus. This provided causal evidence that--by knocking out the pattern of brain activity correlated with emotional memory--stimulation was also selectively diminishing emotional memory.

Depression Acts Similarly to Brain Stimulation

Qasim further hypothesized that depression, which can involve dysregulated emotional memory, might act similarly to brain stimulation. He analyzed patients' emotional memory in parallel with mood assessments they took to characterize their psychiatric state. And, in fact, in the subset of patients with depression, the team observed a concurrent decrease in emotion-mediated memory and high-frequency activity in the hippocampus and amygdala.

"By combining stimulation, recording, and psychometric assessment, they were able to demonstrate causality to the degree that you don't always see in studies with human brain recordings," said Bradley Lega, a neurosurgeon and scientist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and not an author on the paper. "We know high-frequency activity is associated with neuronal firing, so these findings open new avenues of research in humans and animals about how certain stimuli engage neurons in memory circuits."

Next Steps

Qasim, currently a postdoctoral researcher at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai, is pursuing this avenue of research by investigating how individual neurons in the human brain fire during emotional memory processes. Qasim and Jacobs hope their work might also inspire animal research exploring how this high-frequency activity is linked to norepinephrine, a neurotransmitter linked to attentional processes that they theorize might be behind the enhanced memory for emotional stimuli. Finally, they hope that future research will target high-frequency activity in the amygdala-hippocampal circuit to strengthen and protect memory - particularly emotional memory.

"Our emotional memories are one of the most critical aspects of the human experience, informing everything from our decisions to our entire personality," Qasim added. "Any steps we can take to mitigate their loss in memory disorders or prevent their hijacking in psychiatric disorders is hugely exciting."

Attribution/Source(s): This peer reviewed publication was selected for publishing by the editors of Disabled World (DW) due to its relevance to the disability community. Originally authored by Columbia University School of Engineering and Applied Science and published on 2023/01/19, this content may have been edited for style, clarity, or brevity.