How Marital Status and Age Gaps Influence Life Expectancy

Author: Max-Planck-Gesellschaft

Published: 2010/05/12 - Updated: 2025/05/08

Publication Details: Peer-Reviewed, Informative

Category Topic: Offbeat News - Related Publications

Page Content: Synopsis - Introduction - Main - Insights, Updates

Synopsis: This article, based on peer-reviewed research from the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, examines how marital status and age differences between spouses affect life expectancy. It finds that marriage generally benefits both men and women by raising their life expectancy compared to unmarried individuals, but the dynamics are nuanced: men with younger wives tend to live longer, while women with younger husbands actually face a higher mortality risk-about 20% greater if their partner is seven to nine years younger. The study challenges longstanding assumptions about the health benefits of marrying a younger spouse for women, suggesting that social norms and the resulting support networks likely play a role in these outcomes. The research is authoritative, drawing on data from nearly two million Danish couples and correcting for earlier methodological flaws, making it especially valuable for policymakers, seniors, people with disabilities, and anyone interested in the intersection of social relationships and health. Its findings are particularly relevant for those considering long-term partnership decisions, as well as for healthcare providers and advocates supporting older adults and individuals with disabilities - Disabled World (DW).

- Definition: Life Expectancy

Life expectancy is a statistical measure of the average time an organism is expected to live, based on the year of its birth, its current age, and other demographic factors like sex. The heritability of lifespan is estimated to be less than 10%, meaning the majority of lifespan variation is attributable to environmental differences rather than genetic variation. However, researchers have identified regions of the genome that can influence the length of life and the number of years in good health.

Introduction

Marriage is more beneficial for men than women - at least for those who want a long life. Previous studies have shown that men with younger wives live longer. While it had long been assumed that women with younger husbands also live longer, in a new study Sven Drefahl from the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (MPIDR) in Rostock, Germany, has shown that this is not the case. Instead, the more significant the age difference between the husband, the lower the wife's life expectancy. This is the case irrespective of whether the woman is younger or older than her spouse.

Main Content

Related to life expectancy choosing a wife is easy for men - the younger, the better.

The mortality risk of a husband who is seven to nine years older than his wife is reduced by eleven percent compared to couples where both partners are the same age. Conversely, a man dies earlier when he is younger than his spouse.

Researchers have thought this data holds for both sexes for years. They assumed an effect called "health selection" was in play; those who select younger partners can do so because they are healthier and thus already have a higher life expectancy. It was also thought that a younger spouse has a positive psychological and social effect on an older partner and can be a better caretaker in old age, helping to extend the partner's life.

"These theories now have to be reconsidered", says Sven Drefahl from MPIDR. "It appears that the reasons for mortality differences due to the age gap of the spouses remain unclear."

Using data from almost two million Danish couples, Drefahl was able to eliminate the statistical shortcomings of earlier research and showed that the best choice for a woman is to marry a man of the same age; an older husband shortens her life, and a younger one, even more, so.

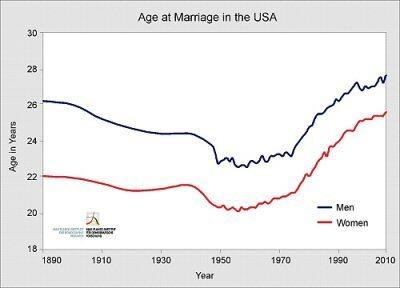

According to Drefahl's study, published May 12th in the journal Demography, women marrying a partner seven to nine years younger increase their mortality risk by 20 percent. Hence, "health selection" can't be true for women; healthy women don't go chasing after younger men. While many studies on mate selection show that women mostly prefer men the same age, most of them end up with an older husband. In the United States, on average, a groom is 2.3 years older than his bride. (see figure 2).

"It's not that women couldn't find younger partners; the majority just don't want to", says Sven Drefahl. "It is also doubtful that older wives benefit psychologically and socially from a younger husband."

This effect only seems to work for men. "On average, men have fewer and lesser quality social contacts than those of women," says Sven Drefahl. Thus, unlike the benefits of a younger wife, a younger husband wouldn't help extend the life of his older wife by taking care of her, going for a walk with her, and enjoying late life together. She already has friends for that. The older man, however, doesn't.

Women don't benefit from having a younger partner, but why does he shorten their lives?

"One of the few possible explanations is that couples with younger husbands violate social norms and thus suffer from social sanctions," says Sven Drefahl.

Since marrying a younger husband deviates from what is normal, these couples could be regarded as outsiders and receive less social support. This could result in a less joyful and stressful life, reduced health, and increased mortality.

While the new MPIDR study shows that marriage disadvantages most women when they are not the same age as their husbands, it is not true that marriage, in general, is unfavorable. Being married raises the life expectancy of both men and women above those unmarried. Women are also generally better off than men; worldwide, their life expectancy exceeds that of men by a few years.

The Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research in Rostock (MPIDR) investigates the structure and dynamics of populations. It focuses on issues of political relevance such as demographic change, aging, fertility, the redistribution of work throughout life, and aspects of evolutionary biology and medicine. The MPIDR is one of Europe's largest demographic research bodies and one of the worldwide leaders in the field. It is part of the Max Planck Society, the internationally renowned German Research Society.

Insights, Analysis, and Developments

Editorial Note: The article's insights underscore the complex interplay between social expectations, partnership choices, and health outcomes. While marriage can confer significant longevity benefits, especially for men, the impact of age differences and societal attitudes toward non-traditional unions should not be underestimated. For individuals navigating aging, disability, or changing family structures, understanding these subtleties can inform more supportive social policies and personal decisions about relationships and care in later life - Disabled World (DW).Attribution/Source(s): This peer reviewed publication was selected for publishing by the editors of Disabled World (DW) due to its relevance to the disability community. Originally authored by Max-Planck-Gesellschaft and published on 2010/05/12, this content may have been edited for style, clarity, or brevity.