Stem-Cell Derived Adrenal Gland Organoids Advance Therapy

Author: University of Pennsylvania

Published: 2022/11/22 - Updated: 2026/01/19

Publication Details: Peer-Reviewed, Research, Study, Analysis

Category Topic: Organoids - Related Publications

Page Content: Synopsis - Introduction - Main - Insights, Updates

Synopsis: This research reports peer-reviewed findings on creating adrenal gland organoids from human inducible pluripotent stem cells that closely replicate early adrenal structure and hormone function in vitro, including response to the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, offering a novel model for studying adrenal insufficiencies and drug screening. The authoritative study, published with rigorous molecular and functional validation by a University of Pennsylvania team, is useful for clinicians, researchers, patients with adrenal disorders, seniors and individuals with disabilities by advancing regenerative and therapeutic avenues beyond lifelong hormone replacement therapy - Disabled World (DW).

- Definition: Adrenal Glands

Adrenal glands, also known as suprarenal glands, are small, triangular-shaped glands on both kidneys. The role of the adrenal glands in your body is to release certain hormones directly into the bloodstream. The adrenal cortex produces three main types of steroid hormones: mineralocorticoids, glucocorticoids, and androgens. Many of these hormones affect how the body responds to stress; some are vital to existence. Both parts of the adrenal glands, the adrenal cortex and the adrenal medulla perform distinct and separate functions. Two common ways adrenal glands cause health issues are by producing too little or too many certain hormones, leading to hormonal imbalances. Various diseases of the adrenal glands or the pituitary gland can cause these adrenal function abnormalities.

Introduction

Sitting atop the kidneys, the adrenal gland plays a pivotal role in maintaining a healthy body. Responding to signals from the brain, the gland secretes hormones that support critical functions like blood pressure, metabolism, and fertility.

Main Content

People with adrenal gland disorders, such as primary adrenal insufficiency, in which the gland does not release sufficient hormones, can suffer fatigue, dangerously low blood pressure, coma, and even death if untreated. No cure for primary adrenal insufficiency exists, and the lifelong hormone-replacement therapy used to treat it carries significant side effects.

A preferable alternative would be a regenerative medicine approach, regrowing a functional adrenal gland capable of synthesizing hormones and appropriately releasing them in tune with the brain's feedback. With a new study in the journal Developmental Cell, researchers from the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine coaxed stem cells in a petri dish to divide, mature, and take on some of the functions of a human fetal adrenal gland, bringing that goal one step closer.

"This is a proof-of-principle that we can create a system grown in a dish that functions nearly identically to a human adrenal gland in the early stages of development," says Kotaro Sasaki, senior author and an assistant professor at Penn Vet. "A platform like this could be used to understand the genetics of adrenal insufficiency better and even for drug screening to identify better therapies for people with these disorders."

Sasaki says his team aimed to use human inducible pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which can give rise to various cell types, to mimic the stages of normal human adrenal development. During this process, the cells would get directed to take on the characteristics of the adrenal gland.

To begin, the researchers used what's known as an "organoid culture" system, in which cells grow first as a floating aggregate for three weeks, then on a membrane exposed to air on one side, promoting better survival and allowing them to increase in three dimensions. Utilizing a carefully selected growth medium, they prompted the iPSCs to elicit an intermediate tissue type in the adrenal development process, the posterior intermediate mesoderm (PIM).

After verifying they had cultured PIM-like cells, the researchers directed those cells to transition to the next stage, adrenocortical progenitor-like cells, during which cells turn on markers indicating they have "committed" to becoming adrenal gland cells.

Molecular assays to check for adrenal markers and transmission electron microscope analyses all told Sasaki and colleagues they were on the right track to recreating a tissue resembling the early adrenal gland.

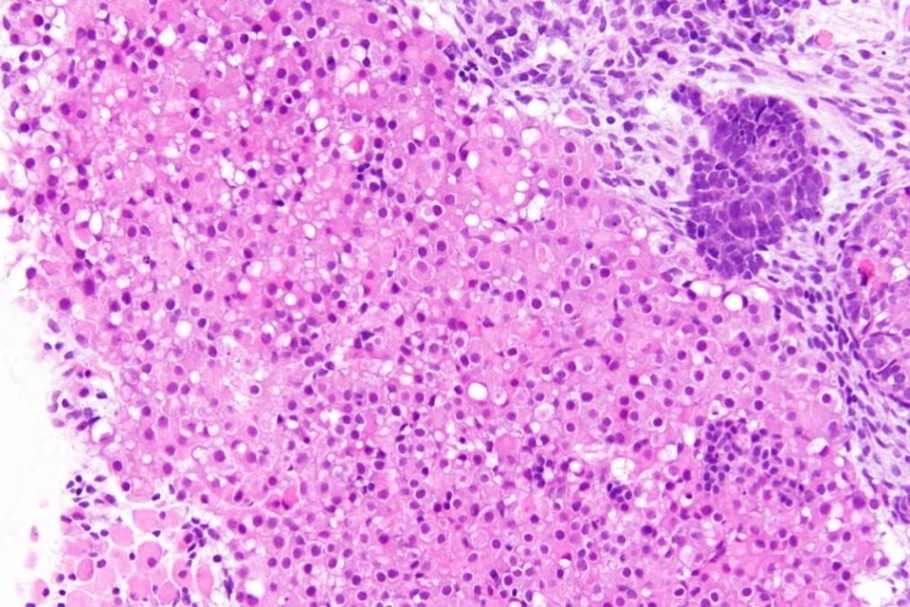

"The process we developed was highly efficient, with around 50% of cells in organoids acquiring adrenocortical cell fate," says Michinori Mayama, a postdoc in Sasaki's lab and a lead author on the study. "The ovoid cells with voluminous pink cytoplasm and relatively small nuclei that we saw in our cultures are very characteristic of human adrenal cells at that stage."

Sasaki, Mayama, and the rest of the research team performed several tests to evaluate how closely the functionality of the cells they had cultivated mirrored that of a human adrenal gland. They found that lab-grown cells produced steroid hormones, like DHEA, just as the "real-life" equivalent would.

"In vitro, we can produce much of the same steroids that are produced in vivo," Mayama says.

They also showed that the cells they grew could respond to what's known as the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, a feedback loop that governs communication from the brain to the adrenal gland and back again.

"We used drugs that normally suppress adrenal DHEA production and showed that our iPSC-derived adrenal cells respond similarly to these drugs, with a marked reduction of hormone production," says Sasaki. "This means that you can use this system for screening drugs that target adrenal hormone production, which could benefit patients with excessive adrenal hormone production or with a prostate cancer that exploits adrenal hormones for their growth."

As the researchers refine their system, they hope to generate more of the gradations in tissue type that occur in a mature adult adrenal gland.

Such a platform opens opportunities to learn more about the still-mysterious adrenal gland. In particular, Sasaki notes that it could be leveraged to probe the genetic basis of adrenal insufficiencies and other diseases, such as adrenal carcinomas. Ultimately, the approach used to create this gland-in-a-dish may one day work to reconstitute a functioning brain-adrenal gland feedback loop in people with adrenal gland disorders.

"This is a first-of-its-kind study," says Sasaki. "The field of cell therapy holds so much promise for treating not just adrenal insufficiencies but other hormone-driven diseases: hypertension, Cushing syndrome, polycystic ovary syndrome, and more."

Notes Regarding the Study

- 1 - Kotaro Sasaki is an assistant professor in the Department of Biomedical Sciences at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine.

- 2 - Michinori Mayama is a postdoctoral fellow in Penn Vet's Department of Biomedical Sciences.

- 3 - Sasaki and Mayama's coauthors were Penn Vet's Yuka Sakata, Keren Cheng, and Yasunari Seita; Penn Medicine's Andrea Detlefsen, Clementina A. Mesaros, Trevor M. Penning, Wenli Yang, and Jerome F. Strauss III; Kyosuke Shishikura of Penn's Department of Chemistry; and Richard J. Auchus of the University of Michigan. Sakata, Cheng, and Mayama were co-first authors of the study. Sasaki was the senior author.

- 4 - The study was supported, in part, by the Silicon Valley Community Foundation (Grant 2019-197906) and the Good Ventures Foundation (Grant 10080664).

Adrenal Cancer: Symptoms, Stages, Information

Insights, Analysis, and Developments

Editorial Note: By successfully coaxing stem cells to acquire adrenal gland identity and produce key steroid hormones with appropriate regulatory feedback, this study not only sets a new standard for endocrine organoid models but also paves the way for precision-targeted research into adrenal diseases and potential future therapies that more closely mimic natural physiology, which could reduce treatment burdens for patients and enhance biomedical understanding of hormone regulation - Disabled World (DW).Attribution/Source(s): This peer reviewed publication was selected for publishing by the editors of Disabled World (DW) due to its relevance to the disability community. Originally authored by University of Pennsylvania and published on 2022/11/22, this content may have been edited for style, clarity, or brevity.