Human Brain Organoids Implanted in Mice Respond to Visual Stimuli

Author: University of California - San Diego

Published: 2022/12/29 - Updated: 2026/01/19

Publication Details: Peer-Reviewed, Research, Study, Analysis

Category Topic: Organoids - Related Publications

Page Content: Synopsis - Introduction - Main - Insights, Updates

Synopsis: This research presents peer-reviewed findings that human cortical brain organoids implanted in the mouse cortex establish functional neural connections and respond to visual stimuli similarly to surrounding brain tissue, observed through combined transparent graphene electrode recordings and two-photon imaging over several months. The work, published in Nature Communications and led by a multidisciplinary team at the University of California, San Diego, demonstrates real-time electrophysiological and optical responses to external visual input and suggests robust synaptic integration between human organoid tissue and host neural networks at the electrophysiological level. These results are authoritative due to the innovative multimodal monitoring methodology and peer-reviewed validation, offering useful insights for neurological disease modeling, neural prosthetic development, and research relevant to people with sensory impairments or neurodegenerative conditions - Disabled World (DW).

- Definition: Human Cortical Organoids

A cerebral organoid, or brain organoid, is an artificially grown, in vitro, miniature organ resembling the brain. Cerebral organoids are created by culturing pluripotent stem cells in a three-dimensional rotational bioreactor and develop over months. Human stem cell-derived cortical organoids are now widely used to model human cortical development in physiological and pathological conditions, as they offer the advantage of recapitulating human-specific aspects of corticogenesis that were previously inaccessible. Using human pluripotent stem cells to create in vitro cerebral organoids allows researchers to summarize current developmental mechanisms for human neural tissue and study the roots of human neurological diseases.

Introduction

Multimodal Monitoring of Human Cortical Organoids Implanted in Mice Reveal Functional Connection With Visual Cortex.

A team of engineers and neuroscientists has demonstrated for the first time that human brain organoids implanted in mice have established functional connectivity to the animals' cortex and responded to external sensory stimuli. The implanted organoids reacted to visual stimuli in the same way as surrounding tissues, an observation that researchers were able to make in real time over several months thanks to an innovative experimental setup that combines transparent graphene microelectrode arrays and two-photon imaging.

Main Content

The team, led by Duygu Kuzum, a faculty member in the University of California San Diego Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, details their findings in the Dec. 26 issue of the journal Nature Communications. Kuzum's team collaborated with researchers from Anna Devor's lab at Boston University, Alysson R. Muotri's lab at UC San Diego, and Fred H. Gage's lab at the Salk Institute.

Human cortical organoids are derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells, usually from skin cells. These brain organoids have recently emerged as promising models to study the development of the human brain, as well as a range of neurological conditions.

But until now, no research team has demonstrated that human brain organoids implanted in the mouse cortex could share the same functional properties and react to stimuli similarly. This is because the technologies used to record brain function are limited and generally unable to record only a few milliseconds of activity.

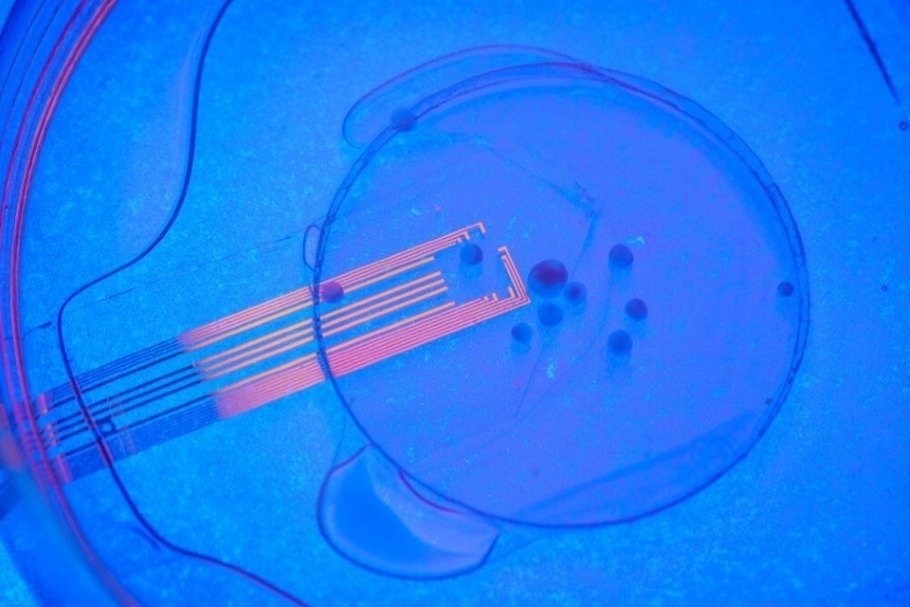

The UC San Diego-led team solved this problem by developing experiments that combine microelectrode arrays made from transparent graphene and two-photon imaging. This microscopy technique can image living tissue up to one millimeter in thickness.

"No other study has been able to record optically and electrically at the same time," said Madison Wilson, the paper's first author and a Ph.D. student in Kuzum's research group at UC San Diego. "Our experiments reveal that visual stimuli evoke electrophysiological responses in the organoids, matching the responses from the surrounding cortex."

The researchers hope that this combination of innovative neural recording technologies to study organoids will serve as a unique platform to comprehensively evaluate organoids as models for brain development and disease and investigate their use as neural prosthetics to restore function to lost, degenerated, or damaged brain regions.

"This experimental setup opens up unprecedented opportunities for investigations of human neural network-level dysfunctions underlying developmental brain diseases," said Kuzum.

Kuzum's lab first developed the transparent graphene electrodes in 2014 and has been advancing the technology since then. The researchers used platinum nanoparticles to lower the impedance of graphene electrodes by 100 times while keeping them transparent. The low-impedance graphene electrodes can record and image neuronal activity at macroscale and single-cell levels.

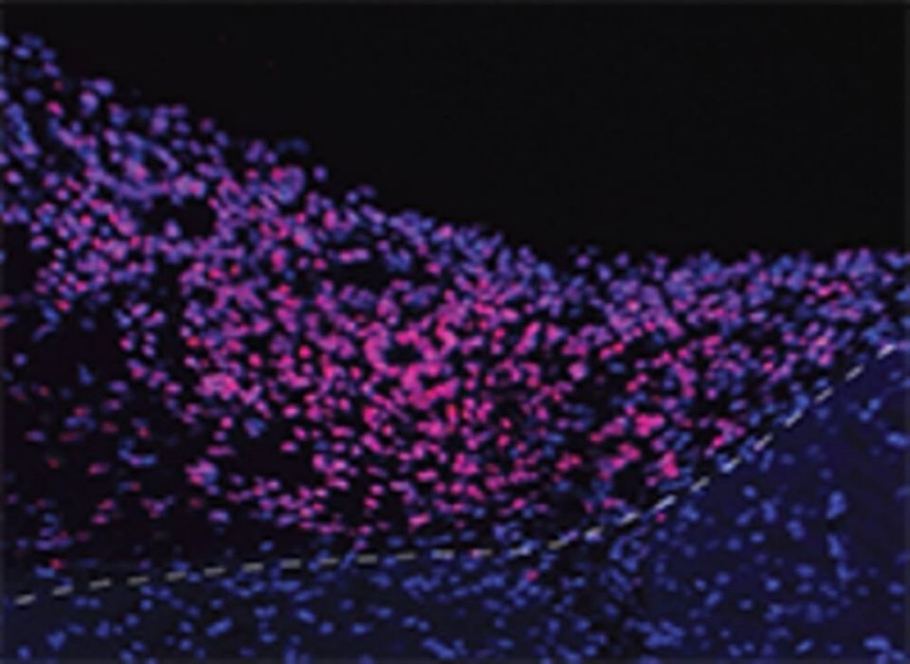

By placing these electrodes on top of the transplanted organoids, researchers could record neural activity electrically from both the implanted organoid and the surrounding host cortex in real time. Using two-photon imaging, they also observed that mouse blood vessels grew into the organoid providing necessary nutrients and oxygen to the implant.

Researchers applied a visual stimulus-an optical white light LED-to the mice with implanted organoids while the mice were under two-photon microscopy. They observed electrical activity in the electrode channels above the organoids showing that the organoids were reacting to the stimulus in the same way as the surrounding tissue.

The electrical activity propagated from the area closest to the visual cortex in the implanted organoids area through functional connections. In addition, their low-noise transparent graphene electrode technology enabled the electrical recording of spiking activity from the organoid and the surrounding mouse cortex.

Graphene recordings showed increases in the power of gamma oscillations and phased locking of spikes from organoids to slow oscillations from the mouse visual cortex. These findings suggest that the organoids had established synaptic connections with surrounding cortex tissue three weeks after implantation and received functional input from the mouse brain.

Researchers continued these chronic multimodal experiments for eleven weeks and showed functional and morphological integration of implanted human brain organoids with the host mice cortex.

Next steps include longer experiments involving neurological disease models and incorporating calcium imaging in the experimental setup to visualize spiking activity in organoid neurons. Other methods could also trace axonal projections between organoid and mouse cortex.

"We envision that further along the road, this combination of stem cells and neurorecording technologies will be used for modeling disease under physiological conditions; examining candidate treatments on patient-specific organoids; and evaluating organoids' potential to restore specifically lost, degenerated or damaged brain regions," Kuzum said.

The work was funded through the National Institutes of Health and the Research Council of Norway, as well as the National Science Foundation.

Insights, Analysis, and Developments

Editorial Note: The capacity of human brain organoids to form functional connections and exhibit stimulus-evoked activity in vivo represents a significant advance in neuroscience, not only refining how researchers model human neural circuit function but also laying groundwork for future translational applications in neurodegenerative disease research and sensory restoration strategies. Continued exploration of this technology may reshape preclinical paradigms and accelerate innovations at the intersection of stem cell biology, neural engineering, and therapeutic neuroscience - Disabled World (DW).Attribution/Source(s): This peer reviewed publication was selected for publishing by the editors of Disabled World (DW) due to its relevance to the disability community. Originally authored by University of California - San Diego and published on 2022/12/29, this content may have been edited for style, clarity, or brevity.