Stem Cells Create Synthetic Mouse Embryos Without Eggs

Author: Weizmann Institute of Science

Published: 2022/08/03 - Updated: 2026/01/19

Publication Details: Peer-Reviewed, Research, Study, Analysis

Category Topic: Regenerative Medicine - Related Publications

Page Content: Synopsis - Introduction - Main - Insights, Updates

Synopsis: This peer-reviewed research published in Cell presents a groundbreaking study from the Weizmann Institute of Science demonstrating how scientists created synthetic mouse embryo models using only stem cells cultured in petri dishes, completely bypassing the need for eggs, sperm, or a womb. The work builds on advanced stem cell reprogramming techniques and a specialized mechanical device that simulates natural embryonic development conditions outside the womb. These synthetic models developed normally until day 8.5 of gestation, forming beating hearts, functioning blood circulation, brains, neural tubes, and intestinal tracts with 95% structural and genetic similarity to natural embryos. The findings hold significant value for people with disabilities and medical conditions requiring organ transplants, as this approach could eventually provide an unlimited source of functional tissues and organs for transplantation while reducing dependence on donor availability. The research also advances understanding of birth defects and developmental disorders, potentially leading to better prevention and treatment strategies that could directly benefit individuals affected by congenital conditions - Disabled World (DW).

- Definition: Embryo

An embryo is the early stage of the development of a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after the fertilization of the female egg cell by the male sperm cell. The resulting fusion of these two cells produces a single-celled zygote that undergoes many cell divisions that make cells known as blastomeres. In humans, embryo is the term applied to the unborn child until the end of the seventh week following conception; from the eighth week, the unborn child is called a fetus. In other multicellular organisms, the word "embryo" can be used more broadly to describe any early developmental or life cycle stage before birth or hatching.

Introduction

Without the egg, sperm, or womb: synthetic mouse embryo models created solely from stem cells. The method opens new vistas for studying how stem cells self-organize into organs and may help produce transplantable tissues in the future.

Main Content

An egg meets a sperm - a necessary first step in life's beginnings and a common first step in embryonic development research. But in a Weizmann Institute of Science study published today in Cell, researchers have grown synthetic embryo models of mice outside the womb by starting solely with stem cells cultured in a petri dish - that is, without using fertilized eggs. The method opens new horizons for studying how stem cells form various organs in the developing embryo. It may one day make it possible to grow tissues and organs for transplantation using synthetic embryo models.

"The embryo is the best organ-making machine and the best 3D bioprinter - we tried to emulate what it does," says Prof. Jacob Hanna of Weizmann's Molecular Genetics Department, who headed the research team.

He explains that scientists already know how to restore mature cells to "stemness" - pioneers of this cellular reprogramming had won a Nobel Prize in 2012. But going in the opposite direction, causing stem cells to differentiate into specialized body cells, not to mention form entire organs, has proved much more problematic.

"Until now, in most studies, the specialized cells were often either hard to produce or aberrant, and they tended to form a mishmash instead of well-structured tissue suitable for transplantation. We overcame these hurdles by unleashing the self-organization potential encoded in the stem cells."

Hanna's team built on two previous advances in his lab. One was an efficient method for reprogramming stem cells back to a naïve state - that is, to their earliest stage - when they have the greatest potential to specialize into different cell types.

The other, described in a scientific paper in Nature in March 2021, was the electronically controlled device the team had developed over seven years of trial and error for growing natural mouse embryos outside the womb. The device keeps the embryos bathed in a nutrient solution inside beakers that move continuously, simulating how nutrients are supplied by material blood flow to the placenta and closely controls oxygen exchange and atmospheric pressure. In the earlier research, the team successfully used this device to grow natural mouse embryos from day 5 to day 11.

In the new study, the team set out to grow a synthetic embryo model solely from naïve mouse stem cells cultured for years in a petri dish, dispensing with the need for starting with a fertilized egg. This approach is extremely valuable because it could largely bypass the technical and ethical issues of using natural embryos in research and biotechnology. Even in the case of mice, certain experiments are currently unfeasible because they would require thousands of embryos. In contrast, access to models derived from mouse embryonic cells, which grow in lab incubators by the millions, is virtually unlimited.

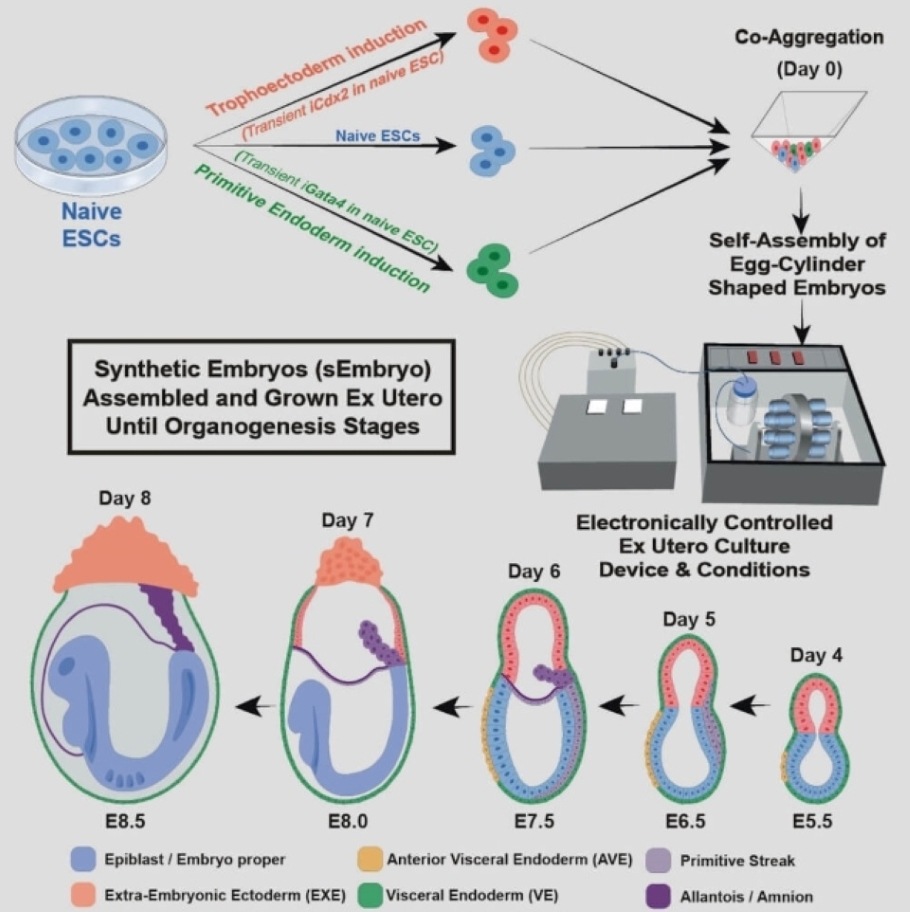

Before placing the stem cells into the device, the researchers separated them into three groups. In one, which contained cells intended to develop into embryonic organs, the cells were left as they were. Cells in the other two groups were pretreated for only 48 hours to overexpress one of two types of genes: master regulators of either the placenta or the yolk sac.

"We gave these two groups of cells a transient push to give rise to extraembryonic tissues that sustain the developing embryo," Hanna says.

Soon after mixing inside the device, the three groups of cells convened into aggregates, most of which failed to develop properly. But about 0.5 percent - 50 of around 10,000 - went on to form spheres, each of which later became an elongated, embryo-like structure. Since the researchers had labeled each group of cells with a different color, they could observe the placenta and yolk sacs forming outside the embryos and the model's development proceeding as in a natural embryo.

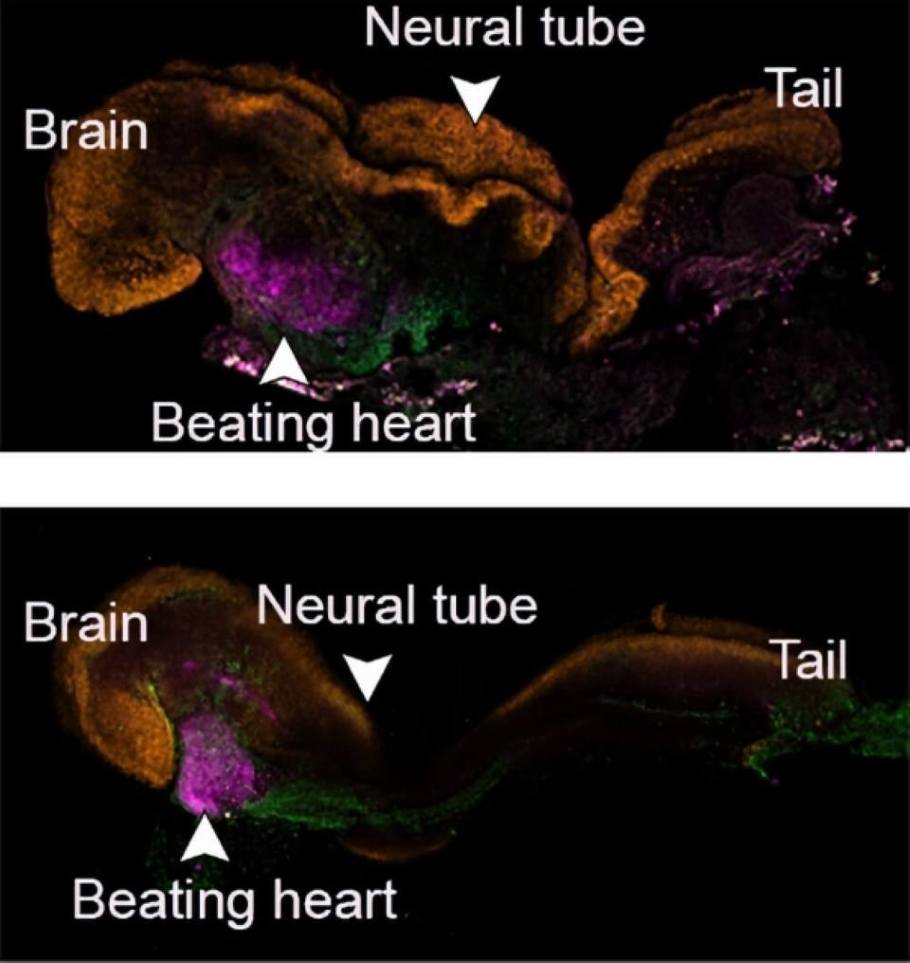

These synthetic models developed normally until day 8.5 - nearly half of the mouse's 20-day gestation - at which stage all the early organ progenitors had formed, including a beating heart, blood stem cell circulation, a brain with well-shaped folds, a neural tube and an intestinal tract. Compared to natural mouse embryos, the synthetic models displayed a 95 percent similarity in the shape of internal structures and the gene expression patterns of different cell types. The organs seen in the models gave every indication of being functional.

For Hanna and other stem cell and embryonic development researchers, the study presents a new arena:

"Our next challenge is to understand how stem cells know what to do - how they self-assemble into organs and find their way to their assigned spots inside an embryo. And because our system, unlike a womb, is transparent, it may prove useful for modeling birth and implantation defects of human embryos."

In addition to helping reduce the use of animals in research, synthetic embryo models might in the future become a reliable source of cells, tissues, and organs for transplantation.

"Instead of developing a different protocol for growing each cell type - for example, those of the kidney or liver - we may one day be able to create a synthetic embryo-like model and then isolate the cells we need. We won't need to dictate to the emerging organs how they must develop. The embryo itself does this best."

Notes:

- To create synthetic mouse embryo models, the researchers started with 27 mouse stem cells divided into three groups.

- Prof. Jacob Hanna's research is supported by the Dr. Barry Sherman Institute for Medicinal Chemistry; the Helen and Martin Kimmel Institute for Stem Cell Research; and Pascal and Ilana Mantoux.

- Video showing a synthetic mouse embryo model on day 8 of its development; it has a beating heart, a yolk sac, a placenta and an emerging blood circulation.

- Video showing how the synthetic mouse embryo models were grown outside the womb - This is how synthetic mouse embryo models were grown outside the womb: a video showing the device in action. Continuously moving beakers simulate the natural nutrient supply, while oxygen exchange and atmospheric pressure are tightly controlled.

The Research Team

This research was co-led by Shadi Tarazi, Alejandro Aguilera-Castrejon, and Carine Joubran of Weizmann's Molecular Genetics Department. Study participants also included Shahd Ashouokhi, Dr. Francesco Roncato, Emilie Wildschutz, Dr. Bernardo Oldak, Elidet Gomez-Cesar, Nir Livnat, Sergey Viukov, Dmitry Lokshtanov, Segev Naveh-Tassa, Max Rose and Dr. Noa Novershtern of Weizmann's Molecular Genetics Department; Montaser Haddad and Prof. Tsvee Lapidot of Weizmann's Immunology and Regenerative Biology Department; Dr. Merav Kedmi of Weizmann's Life Sciences Core Facilities Department; Dr. Hadas Keren-Shaul of the Nancy and Stephen Grand Israel National Center for Personalized Medicine; and Dr. Nadir Ghanem, Dr. Suhair Hanna and Dr. Itay Maza of the Rambam Health Care Campus.

Insights, Analysis, and Developments

Editorial Note: The implications of synthetic embryo technology extend far beyond the laboratory bench and into the realm of practical medicine that could reshape treatment options for millions. While the current work focuses on mouse models, the underlying principles suggest a future where organ shortages become obsolete and patients waiting years for compatible transplants might instead receive custom-grown tissues derived from their own cells. The research team's success in achieving such high fidelity to natural development - complete with beating hearts and organized organ systems - demonstrates that scientists are beginning to decode and replicate nature's most sophisticated biological programs. What makes this particularly relevant for people facing chronic conditions or disabilities is the potential to address not just organ failure, but also to better understand and potentially correct developmental anomalies at their source, offering hope for interventions that were previously confined to science fiction - Disabled World (DW).Attribution/Source(s): This peer reviewed publication was selected for publishing by the editors of Disabled World (DW) due to its relevance to the disability community. Originally authored by Weizmann Institute of Science and published on 2022/08/03, this content may have been edited for style, clarity, or brevity.