Ancient Fossils Solve Evolution Question

Author: University of Oxford

Published: 2022/11/02 - Updated: 2025/11/19

Publication Details: Peer-Reviewed, Anthropology News

Category Topic: Anthropology - Related Publications

Page Content: Synopsis - Introduction - Main - Insights, Updates

Synopsis: This peer-reviewed research from the University of Oxford describes an extraordinary fossil discovery that resolves a longstanding mystery about early animal evolution on Earth. Scientists analyzing 514-million-year-old specimens from China's Yunnan Province found four fossils of Gangtoucunia aspera with remarkably preserved soft tissues, including tentacles and internal organs, revealing that these ancient tube-dwelling creatures were primitive cnidarians - relatives of modern jellyfish and sea anemones. What makes this finding particularly authoritative is its publication in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B and the exceptional preservation of soft tissues, which almost never survive the fossilization process, allowing researchers to definitively classify organisms that had puzzled paleontologists for generations.

The discovery settles debates about which animals first developed hard skeletons during the Cambrian Explosion approximately 550-520 million years ago, demonstrating that simple cnidarians were among the pioneers of skeletal construction. For anyone interested in understanding how life evolved its fundamental structures - from the calcium phosphate in our teeth and bones to the basic body plans seen across the animal kingdom - this research offers rare, concrete evidence about a pivotal moment in biological history when diverse life forms suddenly appeared in the fossil record - Disabled World (DW).

- Definition: Soft Tissue Fossils

The hard parts of organisms, such as bones, shells, and teeth, have a better chance of becoming fossils than softer parts. Soft-tissue fossils are very rare because skin, eyes, guts, and brains are much more difficult to preserve than skeletons. The formation of a mineral concretion around a bone protects biomolecules inside it from hydrolysis by groundwater. Infusion and coating with iron and iron compounds at a critical point in the decay process protects cells within a bone from autolysis. Cross-linking and association with bone mineral surfaces provide added protection to a bone's collagen fibers. These protective factors can result in soft-tissue preservation that lasts millions of years. Soft tissue fossils are generally found in rocks rich in the mineral berthierine, one of the main clay minerals identified as toxic to decay bacteria. Although the soft-bodied organisms and the animals' soft tissues may be preserved through various early diagenetic processes, such as replication by clay minerals, calcification, or pyritization, the mineral most commonly preserving soft tissues is apatite.

Introduction

An exceptionally well-preserved collection of fossils discovered in eastern Yunnan Province, China, has enabled scientists to solve a centuries-old riddle in the evolution of life on earth, revealing what the first animals to make skeletons looked like. The results have been published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Main Content

The first animals to build hard and robust skeletons appear suddenly in the fossil record in a geological blink of an eye around 550-520 million years ago during an event called the Cambrian Explosion. Many of these early fossils are simple hollow tubes ranging from a few millimeters to many centimeters in length. However, what sort of animals made these skeletons were almost completely unknown because they lacked preservation of the soft parts needed to identify them as belonging to major groups of animals that are still alive today.

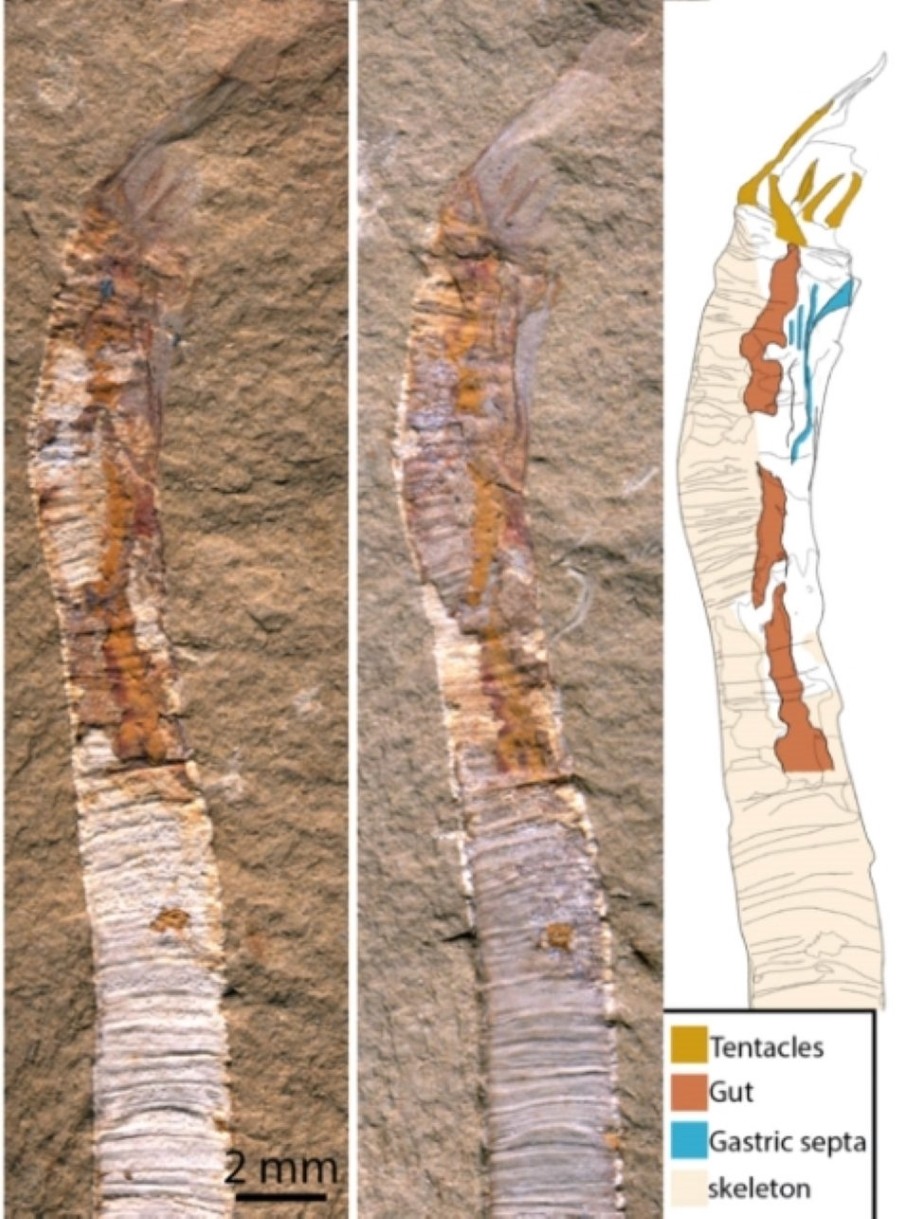

The new collection of 514 million-year-old fossils includes four specimens of Gangtoucunia Aspera with soft tissues still intact, including the gut and mouthparts. These reveal that this species had a mouth fringed with a ring of smooth, unbranched tentacles about 5 mm long. These were likely used to sting and capture prey, such as small arthropods. The fossils also show that Gangtoucunia had a blind-ended gut (open only at one end), partitioned into internal cavities, that filled the length of the tube.

These are features found today only in modern jellyfish, anemones, and their close relatives (known as cnidarians), organisms whose soft parts are extremely rare in the fossil record. The study shows that these simple animals were among the first to build the hard skeletons that make up much of the known fossil record.

According to the researchers, Gangtoucunia would have looked similar to modern scyphozoan jellyfish polyps, with a hard, tubular structure anchored to the underlying substrate. The tentacle mouth would have extended outside the tube but could have been retracted inside the tube to avoid predators. Unlike living jellyfish polyps, the tube of Gangtoucunia was made of calcium phosphate, a hard mineral that makes up our teeth and bones. Using this material to build skeletons has become rare among animals over time.

Corresponding author Dr. Luke Parry, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford, said:

"This really is a one-in-million discovery. These mysterious tubes are often found in groups of hundreds of individuals, but until now, they have been regarded as 'problematic' fossils because we had no way of classifying them. Thanks to these extraordinary new specimens, a key piece of the evolutionary puzzle has been firmly established."

The new specimens demonstrate that Gangtoucunia was not related to annelid worms (earthworms, polychaetes, and their relatives) as had been previously suggested for similar fossils. It is clear that Gangtoucunia's body had a smooth exterior and a gut partitioned longitudinally, whereas annelids have segmented bodies with transverse body partitioning.

The fossil was found at a site in the Gaoloufang section in Kunming, eastern Yunnan Province, China. Here, anaerobic (oxygen-poor) conditions limit the presence of bacteria that normally degrade soft tissues in fossils.

Ph.D. student Guangxu Zhang, who collected and discovered the specimens, said

"The first time I discovered the pink soft tissue on top of a Gangtoucunia tube, I was surprised and confused about what they were. In the following month, I found three more specimens with soft tissue preservation, which was very exciting and made me rethink the affinity of Gangtoucunia. The soft tissue of Gangtoucunia, particularly the tentacles, reveals that it is certainly not a priapulid-like worm as previous studies suggested, but more like a coral, and then I realized that it is a cnidarian."

Although the fossil clearly shows that Gangtoucunia was a primitive jellyfish, this doesn't rule out the possibility that other early tube-fossil species looked very different. From Cambrian rocks in Yunnan province, the research team has previously found well-preserved tube fossils that could be identified as priapulids (marine worms), lobopodians (worms with paired legs, closely related to arthropods today), and annelids.

Co-corresponding author Xiaoya Ma (Yunnan University and University of Exeter) said:

"A tubicolous mode of life seems to have become increasingly common in the Cambrian, which might be an adaptive response to increasing predation pressure in the early Cambrian. This study demonstrates that exceptional soft-tissue preservation is crucial for understanding these ancient animals."

Insights, Analysis, and Developments

Editorial Note: The remarkable preservation of Gangtoucunia aspera demonstrates how fortunate discoveries in paleontology can suddenly illuminate millions of years of evolutionary darkness. These delicate fossils, surviving intact through half a billion years in oxygen-poor sediments, remind us that scientific understanding often hinges on exceptional circumstances - the right conditions, the right location, and researchers persistent enough to recognize significance when they find pink soft tissue clinging to ancient tubes. What began as puzzling "problematic fossils" scattered across Cambrian rock formations has now become a cornerstone for understanding how early animals innovated the hard parts that would eventually become the dominant feature of complex life, from shells to bones to the very teeth we use today - Disabled World (DW).Attribution/Source(s): This peer reviewed publication was selected for publishing by the editors of Disabled World (DW) due to its relevance to the disability community. Originally authored by University of Oxford and published on 2022/11/02, this content may have been edited for style, clarity, or brevity.