Understanding Abiogenesis: How Life Emerged from Non-Life on Early Earth

Author: Ian C. Langtree - Writer/Editor for Disabled World (DW)

Published: 2025/12/06

Publication Type: Anthropology News

Category Topic: Anthropology - Related Publications

Page Content: Synopsis - Introduction - Main - Insights, Updates

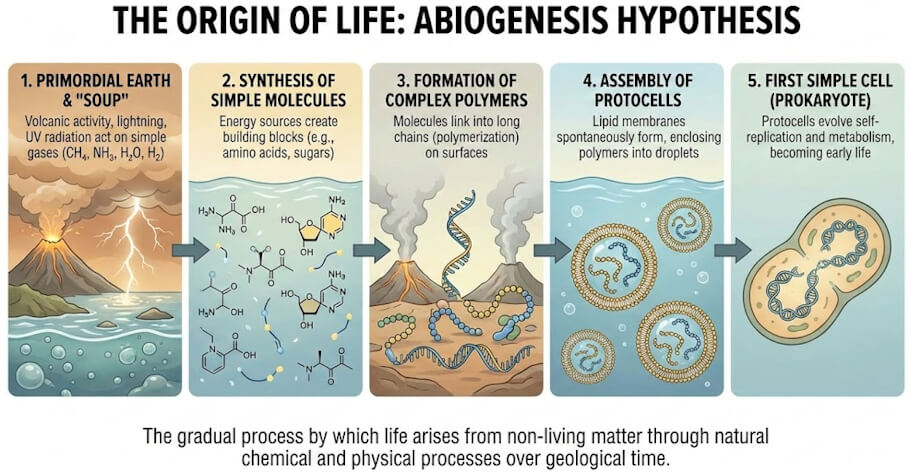

Synopsis: How did life begin? For centuries, this profound question seemed destined to remain forever beyond the reach of science, cloaked in mystery and speculation. Yet in the last few decades, researchers have transformed abiogenesis from philosophical musing into rigorous experimental science, unveiling a compelling story of how nonliving chemistry gradually organized itself into the first living systems on Earth approximately 3.7 to 4.2 billion years ago. Through innovative laboratory experiments that recreate conditions from our planet's ancient past, mathematical analyses that calculate the probability of life's emergence, and exploration of the deep-sea hydrothermal vents where life may have first taken hold, scientists have begun answering humanity's most fundamental question with precision and evidence. This comprehensive examination explores the mechanisms, evidence, and implications of abiogenesis - revealing that life did not emerge through incomprehensible luck, but rather through the elegant, inevitable unfolding of natural law operating under the right conditions - Disabled World (DW).

- Definition: Abiogenesis

Abiogenesis is the natural process by which life emerged from purely nonliving matter on the early Earth, roughly 3.7 to 4.2 billion years ago. Rather than invoking divine creation or external seeding, this scientific concept describes how simple inorganic molecules - through chemical reactions driven by energy from lightning, ultraviolet radiation, and heat - gradually assembled into increasingly complex organic compounds that eventually crossed the threshold into something we'd recognize as alive: systems capable of self-replication, information storage, and evolution. It's fundamentally different from biogenesis, the principle that all modern life comes from preexisting life, which we observe everywhere today. The transition abiogenesis describes is essentially the bridge between pure chemistry and biochemistry, the moment when certain molecular systems began copying themselves, competing for resources, and adapting to their environments through natural selection. Most contemporary evidence points to deep-sea hydrothermal vents as the likely birthplace, where natural electrochemical gradients, abundant minerals, and protective microcompartments provided ideal conditions for this remarkable transformation from nonlife to life.

Introduction

The question of how life began stands as one of science's most profound mysteries. Abiogenesis - the emergence of life from nonliving matter - represents the bridge between chemistry and biology, describing the natural processes through which simple inorganic molecules transformed into the complex, self-replicating systems we recognize as living organisms. Rather than invoking supernatural explanations, scientific evidence increasingly points to a series of chemical and physical processes that occurred on the early Earth, approximately 3.7 to 4.2 billion years ago, which gave rise to our planet's first life-forms [Kipping, 2025]. Understanding abiogenesis requires us to examine not just what happened, but where and how these processes unfolded under conditions radically different from those we observe today.

Main Content

What is Abiogenesis?

Abiogenesis literally means the generation of life from non-life, derived from the Greek words "a" (without) and "genesis" (origin). In scientific terms, abiogenesis refers to the natural, spontaneous processes through which living organisms gradually emerged from purely chemical and physical interactions on the primitive Earth. This is fundamentally different from biogenesis, the principle that all life comes from pre-existing life, which operates in the world we observe today. The abiogenesis hypothesis proposes that the first simple life-forms generated on Earth were indeed primitive, and that they gradually became increasingly complex over vast stretches of geological time [Britannica, 2011].

The emergence of life from nonlife represents a transition from pure chemistry to biochemistry, a moment when certain molecular systems began to replicate themselves, store information, and eventually evolve through natural selection. This transition occurred during what scientists call the Hadean Eon, when Earth was a much different place than it is now - hotter, with a different atmosphere, and with oceans that possessed entirely different chemical compositions than today's waters.

The Historical Development of Abiogenesis Theory

The scientific study of abiogenesis didn't truly begin until the twentieth century, despite philosophers and scientists having speculated about life's origins for millennia. In the 1920s, two scientists independently developed ideas that would form the foundation for modern abiogenesis research. Russian biochemist Alexander Oparin proposed that life developed from microscopic, spontaneously formed spherical aggregates of lipid molecules called coacervates, which could have served as precursors to cells. Meanwhile, British geneticist J.B.S. Haldane developed similar ideas, suggesting that simple organic molecules formed first under the influence of ultraviolet light and gradually became increasingly complex until cells eventually emerged. Together, their work established what became known as the Oparin-Haldane hypothesis, providing the first scientifically grounded framework for understanding life's origins [Britannica, 2011].

The theory remained largely speculative until 1953, when American chemists Harold Urey and Stanley Miller conducted their now-famous experiment. In what became known as the Miller-Urey experiment, they combined warm water with a mixture of gases - water vapor, methane, ammonia, and molecular hydrogen - meant to simulate the primitive ocean, prebiotic atmosphere, and heat from lightning. After just one week, they had produced simple organic molecules, including amino acids, the building blocks of proteins. This groundbreaking result demonstrated that the basic components of life could form spontaneously under conditions thought to have existed on early Earth [Britannica, 2011]. The Miller-Urey experiment fundamentally changed how scientists approached the question of life's origin, shifting it from philosophical speculation to experimental investigation.

The RNA World Hypothesis

One of the most compelling frameworks for understanding abiogenesis is the RNA World hypothesis. This hypothesis proposes that early life was fundamentally based on ribonucleic acid, or RNA, rather than on the DNA-protein systems that characterize all modern life. American molecular biologist Alexander Rich first articulated a coherent version of this hypothesis in 1962, suggesting that the primitive Earth's environment could have produced RNA molecules that eventually acquired enzymatic and self-replicating functions [Wikipedia, 2025].

The RNA World hypothesis addresses what many consider the central paradox of life's origin: modern life depends on three distinct types of interdependent macromolecules - DNA, RNA, and proteins - none of which can function and reproduce without the others. This represents a profound "chicken-and-egg" problem. DNA stores genetic information but cannot replicate itself without protein enzymes. Proteins provide the catalytic machinery for cellular reactions but cannot be made without DNA and RNA instructions. RNA helps bridge these systems but cannot, in modern cells, sustain life alone. The RNA World hypothesis elegantly solves this puzzle by proposing that early life relied on a single molecule, RNA, that possessed both the information-storage capabilities of DNA and the enzymatic capabilities of proteins. This made RNA uniquely suited to serve as the first autonomous self-replicating system [Wikipedia, 2025].

Supporting evidence for the RNA World hypothesis comes from several sources. Most compellingly, we now know that the ribosome - the cellular machine that synthesizes all proteins - actually performs its core catalytic function through RNA, not protein. The peptide bonds that link amino acids together in proteins are formed by ribozymes, which are RNA molecules with catalytic properties. This molecular fossil suggests that when the ribosome evolved, the world was indeed one dominated by RNA. Additionally, recent breakthroughs in prebiotic chemistry have demonstrated that nucleotides, the building blocks of RNA, can form under various plausible prebiotic scenarios. In 2009, researchers showed that activated pyrimidine ribonucleotides could be synthesized under prebiotic conditions, suggesting that RNA-first scenarios, while challenging, remain scientifically plausible [Wikipedia, 2025].

However, the RNA World hypothesis faces significant challenges. Creating RNA from simple chemicals under prebiotic conditions, and especially achieving continuous self-replication without external assistance, remains experimentally elusive. Furthermore, some researchers question whether RNA molecules alone possess sufficient catalytic versatility to have performed all necessary reactions for maintaining a primitive life-form. These challenges have led to alternative proposals, including the "pre-RNA world" hypothesis, which suggests that even simpler genetic materials like threose nucleic acid (TNA) or peptide nucleic acid (PNA) may have preceded RNA. Additionally, some researchers propose that RNA may have worked in concert with other molecules from the beginning, rather than operating in splendid isolation [Wikipedia, 2025; PMC, 2022].

Alternative Pathways to Life: Beyond RNA

While the RNA World hypothesis remains the most extensively studied model for abiogenesis, scientists have proposed numerous alternative or complementary mechanisms. One significant alternative is the metabolism-first hypothesis, which suggests that self-sustaining chemical reaction networks emerged before any genetic material. Rather than focusing on self-replication as the defining feature of early life, this approach emphasizes autocatalytic networks - systems where the products of chemical reactions catalyze their own reproduction. These networks could have existed in the absence of genetic material, drawing energy from natural chemical gradients in the environment.

The PAH world hypothesis represents another fascinating alternative. This model proposes that polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) - complex organic molecules composed of multiple aromatic rings - mediated the synthesis of RNA molecules. PAHs are the most common and abundant of known polyatomic molecules in the visible universe and would have been a likely constituent of the primordial seas. They possess unique chemical properties that could have facilitated RNA synthesis under prebiotic conditions. Additionally, the Panspermia hypothesis, while not strictly an abiogenesis mechanism, suggests that the organic molecules giving rise to life were delivered to Earth by meteorites, comets, or cosmic dust. While organic compounds have indeed been identified in meteorites, most scientists working in the field of origins of life consider the abiogenesis hypothesis - that life arose from non-living matter on Earth itself - to be supported by stronger evidence [Pérez-Collazo et al., 2024].

The Critical Role of Environment: Hydrothermal Vents

Where life began matters almost as much as how it began. For decades, scientists debated whether life's origins lay in shallow, sunlit pools - the famous "warm little pond" that Darwin once imagined - or in some other environment entirely. Today, substantial evidence points to deep-sea hydrothermal vents as one of the most plausible cradles of life.

Hydrothermal vents are cracks in the ocean floor where seawater percolates through hot rock, becomes superheated, and emerges enriched with minerals and heat. These vents exist where tectonic plates are diverging and new oceanic crust forms, such as along mid-ocean ridges. While the first vents discovered in 1977 - called "black smokers" - emit water at approximately 400°C, far too hot for organic molecules to exist, other types of vents operate at much cooler temperatures. Particularly significant are alkaline hydrothermal vents, such as those discovered at the Lost City hydrothermal field near the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. These remarkable features emit hydrogen-rich fluid at temperatures between 40 and 90°C, temperatures far more conducive to organic chemistry [Chemistry World, 2024].

The alkaline vent hypothesis, developed over the last three decades by researchers including Michael Russell of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, proposes a specific mechanism by which life could have emerged at these vents. The hypothesis rests on a crucial observation: alkaline vent fluids are distinctly different from the acidic seawater of the early oceans. When the warm, alkaline water from within the Earth mixes with the cooler, acidic ocean water, an electrochemical gradient forms - a natural potential difference comparable to that of a battery. This gradient resembles, in remarkable ways, the proton gradients that all modern cells use to power their metabolism. The porous mineral walls of the vent chimneys provide natural compartments and catalytic surfaces, offering solutions to the "concentration problem" - the seemingly insurmountable challenge of how organic molecules could achieve sufficient concentrations to participate in chemical reactions [Chemistry World, 2024].

Recent experimental evidence lends compelling support to the hydrothermal vent hypothesis. In 2019, researchers at University College London successfully created protocells - primitive cellular structures - in solutions designed to mimic alkaline hydrothermal vent conditions. Previous experiments had failed to achieve this under such extreme conditions, with protocells typically forming only in cool, fresh water under tightly controlled laboratory conditions. The breakthrough came when researchers realized that previous attempts had used too narrow a range of lipid molecules. Natural environments contain diverse mixtures of different sized lipids. When the researchers recreated protocells using such natural mixtures in hot, salty, alkaline solutions, the molecules not only remained stable but actually formed more readily than they did in idealized laboratory conditions. This finding suggests that the harsh conditions at alkaline hydrothermal vents were not merely tolerable for early life but may have actually been necessary [Lane et al., 2019; ScienceDaily, 2019].

Laboratory simulations of hydrothermal vent conditions have also demonstrated the synthesis of organic molecules critical to life. Using electrochemical reactors that simulate the conditions found at alkaline vents, researchers have shown that carbon dioxide and hydrogen - both products of serpentinization (the geochemical reaction of water with ultramafic minerals from the Earth's mantle) - can be converted into organic molecules. Simple organic compounds including formaldehyde and even trace amounts of ribose (a sugar component of RNA) have been synthesized under these conditions. While yields remain low, the fact that such syntheses are possible at all under realistic prebiotic conditions addresses a major challenge to origin-of-life theories [Chemistry World, 2024].

Recent Developments: Mathematical and Computational Approaches

Contemporary abiogenesis research extends far beyond traditional chemistry experiments. Modern scientists employ sophisticated mathematical and computational tools to address fundamental questions about life's probability and timescale. A particularly significant development came from research published in 2024 and 2025 examining whether abiogenesis occurred rapidly or slowly on Earth.

Using Bayesian analysis - a mathematical framework that incorporates prior knowledge to estimate probabilities - researcher David Kipping conducted an objective analysis of Earth's chronology to determine the odds between rapid and slow abiogenesis scenarios. The analysis compared the earliest evidence of life with the amount of time available for life to emerge. The most recent evidence suggests that the Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA), the most recent organism from which all present-day life descended, existed 4.2 billion years ago [Kipping, 2025]. This timeline is significant because Earth is approximately 4.5 billion years old, and the earliest conditions suitable for life may have existed only 4.2 to 4.1 billion years ago. If evolution typically requires approximately 4 billion years to produce intelligent life-forms like humans, and Earth's biosphere can sustain life for perhaps 5 to 6 billion years total, then the early appearance of LUCA strongly suggests that abiogenesis must have been a relatively rapid process.

Kipping's analysis yielded compelling results. Timing from carbon isotope evidence at 4.1 billion years ago yields odds of 9:1 in favor of rapid abiogenesis, while the more recent LUCA date of 4.2 billion years ago increases the odds to 13:1 - exceeding the canonical threshold of "strong evidence" (10:1 odds) for the first time. This mathematical analysis provides formal support for the hypothesis that life emerges readily under appropriate conditions, rather than being an extraordinarily improbable event [Kipping, 2025].

Another important recent development involves the investigation of the probability of abiogenesis per conducive site. Research by Manasvi Lingam and colleagues, published in 2024, used a Bayesian framework to examine how the number of potential locations for abiogenesis affects the probability of life emerging at any given site. Counterintuitively, they found that when sites suitable for abiogenesis are rare, the probability of life emerging at a given site is actually higher. This suggests that if abiogenesis occurred on Earth, the conditions must have been quite specific and demanding, rather than occurring readily in any aqueous environment [Lingam et al., 2024].

The Question of Sequential versus Nonadaptive Abiogenesis

Recent theoretical work has also challenged traditional assumptions about how abiogenesis must have occurred. Most models of abiogenesis assume that complexity emerged through sequential, step-by-step processes, with each stage building on previous achievements through something akin to natural selection. However, researcher Jeremy England has proposed an alternative: nonadaptive, nonsequential abiogenesis. This hypothesis suggests that life-grade complexity could emerge spontaneously and ungoverned by natural selection, through contingent coalescence under excess capabilities.

In this framework, the emergence of complex life-like systems need not follow the same logic as biological evolution. Rather, life could have emerged through the spontaneous congregation of simpler chemical components into complex structures that happened to possess the properties we now recognize as "alive." Only after this spontaneous emergence of complexity would natural selection begin to operate, refining and optimizing the systems that had already formed. This represents a profound shift in perspective, suggesting that we should search for abiotic systems where trait-fitness covariance emerges and increases, rather than attempting to reconstruct modern biological machinery from simpler precursors [England, 2025].

The Concentration Problem and Microcompartmentalization

One of the most challenging technical problems in understanding abiogenesis is what scientist Christian de Duve termed the "concentration problem." For chemical reactions to occur with any reasonable efficiency, the molecules must be present in sufficient concentrations. In modern cells, enzymes catalyze reactions, helping maintain necessary concentrations of reactants. But in a prebiotic environment, how could the building blocks of life achieve sufficient concentrations to interact and form larger molecules?

The microporous structure of hydrothermal vents provides an elegant solution. The iron-sulfide mineral walls of vent chimneys contain countless tiny pores - spaces on the scale of micrometers or smaller. These natural microcompartments could have concentrated prebiotic chemicals through various mechanisms, including thermophoresis (the movement of particles along temperature gradients) and simple diffusive trapping. Once concentrated within these tiny spaces, organic molecules would be far more likely to encounter one another and react. Furthermore, the mineral walls themselves could provide catalytic surfaces, accelerating crucial chemical reactions. The porous vent structure would have functioned as a natural chemical reactor or, perhaps more poetically, as what some researchers call the "warm little pores" that concentrate and facilitate the chemical processes leading to life [Russell & Hall, 1997; Martin & Russell, 2007].

The Universal Nature of Chemiosmosis

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence linking modern biochemistry to a hydrothermal vent origin concerns chemiosmosis - the mechanism by which all cells harness energy. Every known organism, from the simplest bacteria to humans, uses electrochemical proton gradients across membranes to generate ATP, the molecular currency of energy in cells. The universality of this mechanism suggests it arose very early in evolution, but its origin has long been mysterious.

Alkaline hydrothermal vents naturally maintain such proton gradients. The difference in pH between the alkaline vent fluid and the acidic ocean (a difference of about 3 pH units) mirrors the proton gradients that cells create using energy-consuming pumps. This remarkable convergence suggests that early life-forms may have literally "parasitized" the natural electrochemical gradients of their hydrothermal vent environment, using these gradients directly to drive their metabolic chemistry before evolving their own ATP synthases. As life became more sophisticated and developed the ability to pump their own protons and maintain their own gradients, cells would have gradually become independent of their vent environment, eventually migrating into the open ocean [Lane et al., 2010].

Examples and Experimental Demonstrations

Understanding abiogenesis requires examining concrete examples of how scientists attempt to recreate or simulate prebiotic chemistry. These experiments, while necessarily simplified compared to the actual prebiotic environment, provide crucial insights into what was chemically possible billions of years ago.

The Miller-Urey experiment remains the most famous example. By subjecting a simple mixture of chemicals to electrical discharge, Miller and Urey demonstrated that amino acids could form spontaneously under prebiotic conditions. Modern variations of this experiment, using updated assumptions about early Earth's atmosphere and additional energy sources, have produced even more diverse organic compounds. These experiments have shown that the basic building blocks of life are relatively easy to synthesize from simple precursors, suggesting that the "hard part" of abiogenesis was not acquiring organic molecules, but organizing them into self-replicating, self-organizing systems.

More recent experiments on protocell formation illustrate another crucial transition. Researchers have shown that simple lipid molecules - similar to those that might have formed in prebiotic environments - spontaneously self-assemble into membrane-bound structures called liposomes or vesicles. These artificial protocells can encapsulate other molecules, create internal compartments, and even exhibit some primitive growth and division behaviors. Most remarkably, as mentioned earlier, these protocells form more readily in hot, salty, alkaline conditions mimicking deep-sea vents than they do under idealized laboratory conditions, suggesting that the vent environment actively facilitated cell formation.

Laboratory recreations of hydrothermal vent chemistry have also proven illuminating. By pumping alkaline solutions into iron-rich acidic solutions, researchers have grown tiny chimneys similar to those found at natural vents. These chemical gardens generate small electrical potentials - not enough to power a cell, but enough to demonstrate that the vent environment provides the raw energy driving chemistry. More sophisticated electrochemical reactors, such as Nick Lane's origins of life reactor, have demonstrated that formaldehyde and other organic compounds can be synthesized when hydrogen and carbon dioxide are allowed to react across iron-sulfur mineral catalysts under a proton gradient mimicking vent conditions.

Abiogenesis, Aging, and Disability: Connections and Implications

While abiogenesis primarily addresses questions of Earth's ancient past, understanding how life originated carries surprising relevance to modern gerontology and disability studies. The study of abiogenesis illuminates fundamental principles about how complex biological systems maintain organization and energy production - principles directly applicable to understanding aging and cellular dysfunction in later life.

The discovery that all organisms harness proton gradients for energy production reveals that mitochondrial dysfunction - a hallmark of aging - represents a form of regression toward pre-cellular chemistry. When mitochondria fail to maintain proper proton gradients, cells lose their ability to generate ATP efficiently, resulting in energy depletion. Many age-associated diseases, including neurodegenerative conditions like Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease, involve progressive mitochondrial dysfunction. In some sense, aging involves a gradual loss of the sophisticated energy management systems that evolved over billions of years, a reversal toward less efficient prebiotic chemistry.

Moreover, understanding the concentration problem in abiogenesis - how cellular compartments concentrate necessary molecules to maintain chemical reactions - provides insights into age-related cellular decline. As cells age, the compartmentalization and organization of molecules becomes less efficient. Proteins aggregate rather than remaining in their functional states, and the precise organization of molecules within cellular compartments deteriorates. This loss of molecular organization parallels, in reverse, the organization process that was necessary for life to emerge in the first place.

For individuals with disabilities affecting metabolic function - whether genetic disorders affecting mitochondrial function, conditions like diabetes affecting metabolic regulation, or neurodegenerative diseases - understanding abiogenesis offers both theoretical insights and potential practical applications. Research into prebiotic chemistry and the origins of metabolic pathways has revealed that the fundamental biochemical routes to energy production are surprisingly simple and elegant. This knowledge informs efforts to develop therapies that might restore or enhance metabolic function when it has deteriorated or never properly developed. Additionally, studying how life achieved incredible complexity despite working with only simple molecules and minimal energy gradients offers philosophical perspective to individuals managing the constraints of disability, demonstrating that life - in its origins and throughout its history - has consistently found ways to thrive under limiting conditions.

Unresolved Questions and the Future of Abiogenesis Research

Despite considerable progress, significant questions remain about how life actually originated. While scientists have demonstrated that many prebiotic chemicals can form under various conditions, the transition from chemistry to true biochemistry - from molecules that follow the laws of chemistry to systems that replicate, evolve, and exhibit the organized complexity we recognize as life - remains incompletely understood.

One persistent challenge involves explaining how accurate self-replication could have emerged. Modern replication depends on sophisticated enzymes that are themselves products of evolution. What simpler, purely chemical mechanism could have enabled early molecules to copy themselves with reasonable fidelity? While scientists have identified RNA sequences that can catalyze their own replication, and have shown that RNA can be copied nonenzymatically under certain conditions, these systems are far less efficient than modern replication.

Another major question concerns the origin of compartmentalization. How did protocells acquire membranes that could control what enters and exits while remaining permeable enough to permit necessary exchange with the environment? While scientists have created primitive membrane-bound structures, understanding how these structures became sophisticated enough to allow life to spread beyond its point of origin remains incompletely resolved.

The "metabolism-first versus genes-first" debate continues, with researchers divided on whether metabolic networks or genetic material emerged first. The answer might ultimately be "both simultaneously," with metabolic networks and genetic systems evolving in tandem, each solving problems that the other created. Future research promises to clarify this fundamental question through increasingly sophisticated experiments and computational modeling.

Looking forward, advances in synthetic biology may prove crucial to understanding abiogenesis. By deliberately constructing minimal living systems in the laboratory - systems with only the bare minimum of components necessary to exhibit life-like properties - scientists can test hypotheses about what was necessary for early life. Similarly, expanding the search for life's origins beyond Earth may illuminate the question. If scientists discover life based on entirely different chemistry, on a moon or exoplanet, it would demonstrate that abiogenesis is a general phenomenon, not some extraordinary accident unique to Earth. Conversely, finding prebiotic chemistry on extrasolar worlds similar to what existed on early Earth could provide crucial insights into conditions that favor life's emergence.

Conclusion

Abiogenesis represents one of science's greatest unsolved puzzles and one of its most profound achievements in understanding. While we cannot yet point to a single, completely demonstrated pathway from nonlife to life, the accumulating evidence increasingly suggests a coherent scientific story. Life emerged on early Earth not through miraculous events or implausible chemical leaps, but through the sustained operation of ordinary chemical and physical processes in extraordinary environments.

The evidence points particularly strongly to deep-sea hydrothermal vents, where natural energy gradients, abundant catalytic minerals, and protective microcompartments provided the ideal environment for chemical complexity to emerge. The RNA World hypothesis, though still facing challenges, provides an elegant framework for understanding how molecules could have possessed both genetic and catalytic functions. Mathematical analyses suggest that abiogenesis likely occurred relatively rapidly once appropriate conditions were present, implying that life emerges naturally and perhaps even commonly when conditions permit.

The study of abiogenesis is not merely an exercise in ancient history. Understanding how life originated illuminates the fundamental properties of biological systems and offers insights into aging, cellular function, and the maintenance of life-sustaining complexity. As we develop new experimental techniques, refine our chemical knowledge, and explore other worlds, our understanding of abiogenesis will undoubtedly deepen, bringing us closer to answering perhaps humanity's most profound question: How did life begin?

References

Britannica. (2011). Abiogenesis. In Britannica Online Encyclopedia.

Chemistry World. (2024). Hydrothermal vents and the origins of life. Chemistry World, Feature Article.

England, J. L. (2025). On the feasibility of nonadaptive, nonsequential abiogenesis. Perspectives of Earth and Space Scientists, 6(1), 280.

Kipping, D. (2025). Strong evidence that abiogenesis is a rapid process on Earth analogs. Astrobiology, 25(5), 323–326.

Lane, N., Allen, J. F., & Martin, W. (2010). How did LUCA make a living? Chemiosmotic, autotrophic theories of biochemical origins. BioEssays, 32(4), 271–280.

Lane, N. J., Jordan, S., & Earland, S. (2019). Deep sea vents had ideal conditions for origin of life. Nature Ecology & Evolution.

Lingam, M., Nichols, R., & Balbi, A. (2024). A Bayesian analysis of the probability of the origin of life per site conducive to abiogenesis. Astrobiology, 24(8), 813–823.

Martin, W., & Russell, M. J. (2007). On the origin of biochemistry at an alkaline hydrothermal vent. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 367(1187), 1187–1925.

Pérez-Collazo, C., Carvalho, M. D. C., & Henriques, J. F. (2024). Prebiotic RNA self-assembling and the origin of life: Mechanistic and molecular modeling rationale. In Advances in Protein Molecular and Structural Biology (Vol. 4, Ch. 13).

Russell, M. J., & Hall, A. J. (1997). The emergence of life from iron monosulfide bubbles at a submarine hydrothermal redox and pH front. Journal of the Geological Society, London, 154, 377–402.

ScienceDaily. (2019). Deep sea vents had ideal conditions for origin of life. ScienceDaily.

Wikipedia. (2025). RNA world. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia.

Insights, Analysis, and Developments

Editorial Note: The question of life's origin, once consigned to theology and philosophy, has become one of science's most vibrant frontiers, where biochemistry, geology, physics, and mathematics converge to illuminate our deepest past. The evidence increasingly suggests that life emerged not as a miraculous anomaly but as a natural consequence of ordinary chemistry operating in extraordinary environments - particularly the hydrogen-rich, energy-laden depths of alkaline hydrothermal vents where the first protocells may have organized themselves into self-replicating systems. As we refine our understanding through advancing experimental techniques and contemplate the search for life beyond Earth, we come to appreciate a humbling truth: the same physical and chemical principles that assembled life billions of years ago continue operating today, reminding us that we are not separate from nature's creative processes but rather their direct continuation, shaped by the same elegant laws that transformed a lifeless planet into a living world teeming with consciousness and complexity - Disabled World (DW). Author Credentials: Ian is the founder and Editor-in-Chief of Disabled World, a leading resource for news and information on disability issues. With a global perspective shaped by years of travel and lived experience, Ian is a committed proponent of the Social Model of Disability-a transformative framework developed by disabled activists in the 1970s that emphasizes dismantling societal barriers rather than focusing solely on individual impairments. His work reflects a deep commitment to disability rights, accessibility, and social inclusion. To learn more about Ian's background, expertise, and accomplishments, visit his full biography.

Author Credentials: Ian is the founder and Editor-in-Chief of Disabled World, a leading resource for news and information on disability issues. With a global perspective shaped by years of travel and lived experience, Ian is a committed proponent of the Social Model of Disability-a transformative framework developed by disabled activists in the 1970s that emphasizes dismantling societal barriers rather than focusing solely on individual impairments. His work reflects a deep commitment to disability rights, accessibility, and social inclusion. To learn more about Ian's background, expertise, and accomplishments, visit his full biography.