Fetal Intestine Organoid Development Model Shows Promise

Author: Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center

Published: 2023/05/04 - Updated: 2026/01/19

Publication Details: Peer-Reviewed, Findings

Category Topic: Organoids - Related Publications

Page Content: Synopsis - Introduction - Main - Insights, Updates

Synopsis: This paper reports on a peer-reviewed scientific study that demonstrates how human intestinal organoids transplanted into mice can faithfully mimic key stages of fetal intestinal development, providing an accurate in-vitro model for human tissue formation. By using pluripotent stem cells to generate functioning intestinal structures that recapitulate human morphological, transcriptional, and proteomic development, the research offers an authoritative platform for studying digestive biology and disease mechanisms without using actual human fetuses, which is both ethically sensitive and legally restricted. Such organoid-based models are useful for investigating congenital digestive conditions, testing drug responses, and improving understanding of gut-related health issues that affect people across the lifespan, including seniors and individuals with digestive disabilities - Disabled World (DW).

- Definition: Pluripotent Stem Cells

Pluripotent stem cells are cells that have the capacity to self-renew by dividing and to develop into the three primary germ cell layers of the early embryo and therefore into all cells of the adult body, but not extra-embryonic tissues such as the placenta. Embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells are pluripotent stem cells. Pluripotent stem cells are able to self-renew by dividing and developing into the three primary groups of cells that make up a human body:

- Ectoderm: Giving rise to the skin and nervous system.

- Endoderm: Forming the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts, endocrine glands, liver, and pancreas.

- Mesoderm: Forming bone, cartilage, most of the circulatory system, muscles, connective tissue, and more.

Introduction

"Transplanted Human Intestinal Organoids: A Resource for Modeling Human Intestinal Development" - Development.

Developmental biologists have learned a great deal about how the human digestive tract functions through many years of studies involving fish, frogs, and rodents along with detailed explorations of individual human cells. But nothing quite matches the learning that could be achieved from studying actual human organ systems as they form.

Main Content

Yet for obvious reasons, running experiments on growing human fetuses is both unethical and illegal.

Now a study led by researchers at Cincinnati Children's, published online April 18, 2023, in the journal Development, reports that lab-grown tissues called organoids accurately mimic key development stages of the human intestine.

"Achieving this step is important because we know that many human conditions cannot be duplicated in animal models, nor can we learn everything we want to know from studying human cells that are not functioning together as a system. Now we have a source of functioning tissue that can be interrogated in many ways without involving any fetal tissue," says the study's corresponding author, Michael Helmrath, MD.

Helmrath is the director of surgical research at Cincinnati Children's and co-director of the Center for Stem Cell and Organoid Medicine (CuSTOM). He has been working for more than a decade to study and improve intestine organoids for use in research and potentially for human transplantation.

In 2010, a team led by James Wells, PhD, at Cincinnati Children's successfully used induced pluripotent stem cells to develop the world's first functional human intestinal organoid. Wells, Helmrath and colleagues have been improving upon the model ever since, adding complexity by incorporating both the enteric nervous system and immune cells to reproduce the human intestine.

In their latest study, Helmrath, first author Akaljot Singh, an MD/PhD student, and 11 co-authors show that organoids transplanted into mice (to provide a blood supply and room to grow) follow the same temporal and spatial developmental steps that occur as intestines growing in a human fetus.

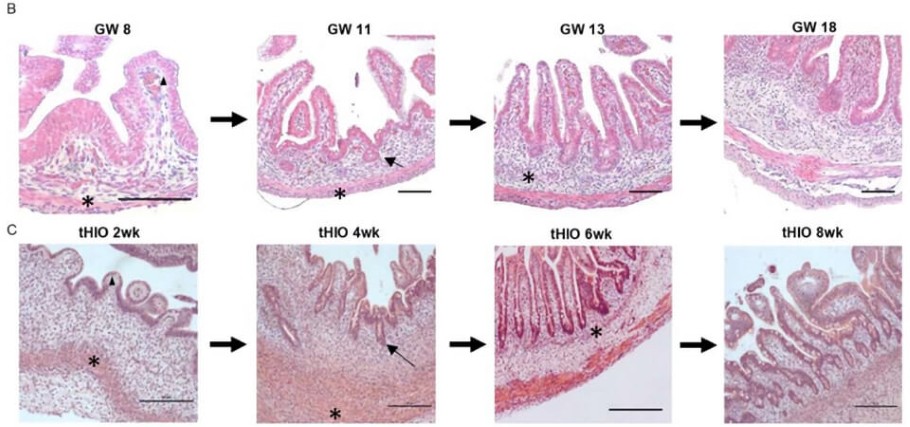

The team used RNA sequencing and other technologies to track the formation of specific cell types and key tissue structures grown for four weeks in a dish and then harvested at two, four, six, and eight weeks post-transplant. They show that the organoids in mice mimic human development that occurs from eight to 18 gestational weeks.

"Our findings suggest that tHIOs (transplanted human intestinal organoids) are a proxy for studying the development of the human fetal intestine. They mimic human fetal intestinal development on a morphological level, transcriptional level, and proteomic level," the study states.

Why are Intestine Organoids Important?

Our intestines do more than help digest our food. They play a central role in our immune response to harmful invaders. They also host populations of commensal (friendly) bacteria and fungi that influence our immune responses and our metabolisms.

Understanding more precisely how and when intestine development goes off-track could shed new light on many conditions, including birth defects, digestive disorders, obesity, and allergy risk. Both healthy intestinal organoids and versions exhibiting disease conditions can serve as improved test platforms to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of virtually any oral medication for any health problem.

Next Steps

More research is needed to validate the organoid development model for certain subpopulations of cell types that were difficult to analyze in this study, Helmrath says.

But with the concept established that human organoids growing in mice can serve as a proxy for fetal development, Helmrath predicts a wave of studies to begin using them.

"This study has already identified several cell populations of interest that appear to play roles we did not recognize previously, including cells that appear to help guide muscle contraction, villi formation, and vascular development," Helmrath says. "In the years to come, we expect tHIOs to support many more discoveries from many labs around the world."

Insights, Analysis, and Developments

Editorial Note: The successful use of transplanted human intestinal organoids to model fetal development represents a significant advance in developmental biology and translational medicine. By capturing critical aspects of human tissue formation in a controlled setting, this research not only deepens scientific understanding of early organogenesis but also creates a practical foundation for future studies into digestive disorders, therapeutic screening, and personalized medicine approaches that may benefit those living with chronic gastrointestinal conditions or related disabilities - Disabled World (DW).Attribution/Source(s): This peer reviewed publication was selected for publishing by the editors of Disabled World (DW) due to its relevance to the disability community. Originally authored by Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center and published on 2023/05/04, this content may have been edited for style, clarity, or brevity.