Health Informatics: Transforming Healthcare Through Technology and Data

Author: Ian C. Langtree - Writer/Editor for Disabled World (DW)

Published: 2026/01/27

Publication Type: Scholarly Paper

Category Topic: Journals - Papers - Related Publications

Page Content: Synopsis - Introduction - Main - Insights, Updates

Synopsis: We're living through a quiet revolution in healthcare that rarely makes headlines but touches nearly every medical interaction we experience. Health informatics - the sophisticated integration of health data, information technology, and clinical expertise - has transformed everything from how doctors write prescriptions to how patients access their own medical records. This isn't just about computers in hospitals; it's about fundamentally reimagining how healthcare information flows between patients, providers, and the systems that support them. For seniors managing multiple chronic conditions, for people with disabilities navigating accessibility barriers, and for everyone seeking more transparent and coordinated care, health informatics promises both remarkable opportunities and sobering challenges. Understanding this field helps us become better advocates for ourselves and our loved ones while critically evaluating the digital health tools that increasingly shape our wellbeing - Disabled World (DW).

- Definition: Health Informatics

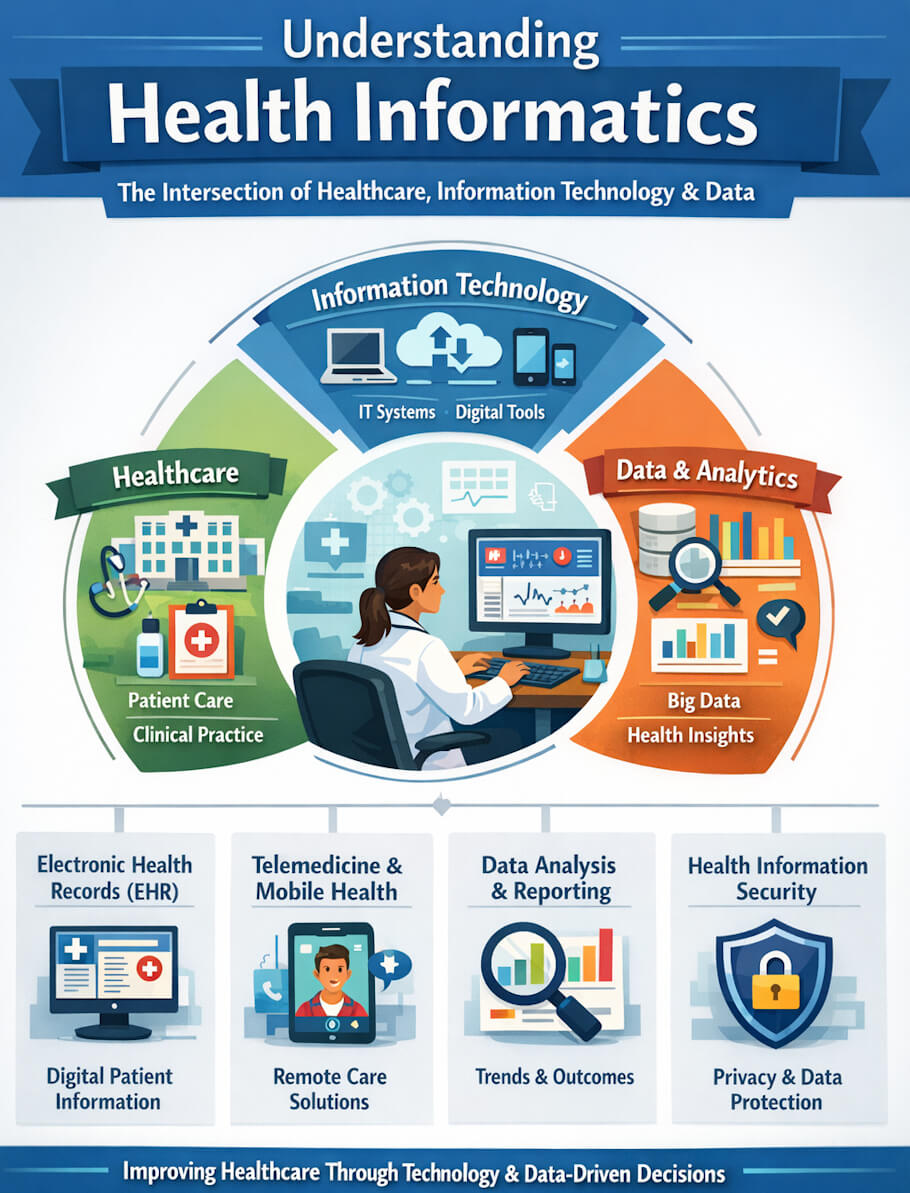

Health informatics is the multidisciplinary field that sits at the intersection of healthcare, information science, and technology, focused on the acquisition, storage, retrieval, and optimal use of health-related data and information. It encompasses everything from the electronic health records that document patient encounters to the clinical decision support systems that help providers make evidence-based choices, from the telemedicine platforms that connect patients and doctors across distances to the data analytics tools that identify population health trends. More than just digitizing paper records, health informatics fundamentally reimagines how we collect, share, and apply health information to improve patient outcomes, enhance quality and safety, reduce costs, and make healthcare more accessible and equitable. The field draws on expertise from clinical practice, computer science, information management, cognitive science, and social science to create systems that don't just manage data, but actually support the complex, nuanced, deeply human work of healthcare delivery. Whether it's helping a pharmacist spot a dangerous drug interaction, enabling a patient to schedule appointments online, or allowing public health officials to track disease outbreaks in real-time, health informatics shapes the infrastructure through which modern medicine operates.

Introduction

Understanding Health Informatics

Health informatics sits at the crossroads where healthcare meets information technology, creating a discipline that's fundamentally changing how we deliver, manage, and experience medical care. At its core, health informatics involves collecting, storing, analyzing, and applying health data to improve patient outcomes, streamline clinical workflows, and make healthcare more accessible to everyone. Think of it as the digital nervous system of modern medicine - connecting patients, providers, laboratories, pharmacies, and insurance companies in ways that would have seemed like science fiction just a generation ago.

The field emerged in the 1960s when hospitals first began experimenting with computerized systems, but it's evolved dramatically since those early days of massive mainframe computers and punch cards (Shortliffe & Cimino, 2021). Today's health informatics encompasses everything from electronic health records (EHRs) that follow patients throughout their care journey, to sophisticated algorithms that can predict disease outbreaks, to mobile apps that help people manage chronic conditions from their smartphones. What makes this field particularly fascinating is how it combines clinical expertise, computer science, information management, and behavioral science to solve real-world healthcare challenges (Hersh, 2020).

Main Content

The Building Blocks of Health Informatics

When healthcare professionals talk about health informatics, they're referring to several interconnected components that work together like instruments in an orchestra. Electronic health records form the foundation - these are comprehensive digital versions of patients' paper charts that contain medical history, diagnoses, medications, treatment plans, immunization dates, allergies, radiology images, and laboratory test results (Benson & Grieve, 2021). Unlike the old paper files that could only exist in one place at one time, EHRs can be accessed simultaneously by different providers in different locations, which proves invaluable when someone needs emergency care far from home.

Beyond EHRs, health information exchange systems allow different healthcare organizations to share patient information securely. Picture a patient who sees a cardiologist at one hospital system, gets physical therapy at a rehabilitation center, and fills prescriptions at a local pharmacy. Health information exchange enables these separate entities to communicate, ensuring everyone involved in that patient's care has access to the same up-to-date information (Adler-Milstein & Pfeifer, 2017). This interconnectedness reduces duplicate testing, prevents dangerous medication interactions, and creates a more cohesive healthcare experience.

Clinical decision support systems represent another crucial component, functioning like incredibly knowledgeable colleagues who never sleep and never forget important details. These systems analyze patient data and provide healthcare providers with evidence-based recommendations at critical decision points (Sutton et al., 2020). For example, if a doctor prescribes a medication that might interact dangerously with something the patient is already taking, the system immediately flags the potential problem. Or if a patient's laboratory results suggest early kidney disease, the system can alert providers to monitor specific parameters more closely.

Telemedicine platforms have exploded in prominence, particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated their adoption. These systems enable patients to consult with healthcare providers remotely through video calls, secure messaging, and remote monitoring devices (Wosik et al., 2020). A person with diabetes might use a glucose monitor that automatically transmits readings to their doctor's office, while someone recovering from surgery might have a video check-in rather than traveling to the clinic. This technology doesn't just add convenience - it fundamentally expands access to care for people who face transportation challenges, live in rural areas, or have difficulty leaving home.

How Health Informatics Impacts the General Population

For the average person navigating the healthcare system, health informatics has already transformed experiences in ways both obvious and subtle. Patient portals have become commonplace, giving people 24/7 access to their own health information, test results, and medical records through secure websites or smartphone apps (Nazi et al., 2020). Rather than waiting days for a nurse to call with lab results, patients can often view them within hours and even see how their values compare to normal ranges. They can request prescription refills, schedule appointments, and communicate with their healthcare team without playing phone tag.

This increased transparency and access to information has shifted the traditional power dynamic in healthcare. Patients arrive at appointments better informed about their conditions, having researched symptoms and treatment options. They can track their health metrics over time, spotting patterns that might not be obvious during brief clinical visits (Greenhalgh et al., 2017). A parent can show the pediatrician a detailed log of their child's fever patterns, or someone with migraines can identify potential triggers by correlating headaches with diet, weather, and stress levels recorded in a health app.

Prescription management has become significantly safer and more convenient through e-prescribing systems. When doctors send prescriptions electronically to pharmacies, it eliminates handwriting errors that once caused serious medication mistakes. The systems also check for drug interactions, allergies, and appropriate dosing based on factors like age and kidney function (Grossman et al., 2017). Patients benefit from faster service at the pharmacy and can often receive notifications when prescriptions are ready for pickup or when it's time for refills.

Public health surveillance has also benefited enormously from health informatics infrastructure. During disease outbreaks, public health officials can monitor emergency department visits, prescription patterns, and laboratory test results to detect and respond to threats more quickly (Klompas et al., 2020). The same systems that support individual patient care contribute to population health by identifying trends, tracking vaccination rates, and helping target interventions where they're needed most.

Special Considerations for Seniors

The aging population stands to gain tremendously from health informatics innovations, though this demographic also faces unique challenges in adopting these technologies. Older adults typically manage multiple chronic conditions simultaneously - perhaps diabetes, heart disease, and arthritis - each with its own medication regimen, specialist appointments, and monitoring requirements (Wildenbos et al., 2018). Health informatics systems excel at coordinating this complexity, ensuring medications don't interact dangerously and that all providers understand the complete clinical picture.

Remote patient monitoring offers particular promise for seniors who want to age in place rather than move to assisted living facilities. Devices can track vital signs like blood pressure, heart rate, weight, and blood glucose, transmitting this data automatically to healthcare providers who can intervene if concerning trends emerge (Pekmezaris et al., 2021). A senior with congestive heart failure might use a smart scale that detects fluid retention before symptoms become severe, allowing medical staff to adjust medications proactively rather than waiting for an emergency. These systems provide peace of mind for both seniors and their adult children, knowing that someone is keeping watch even when family members can't be physically present.

Medication management systems address one of the most common and dangerous problems facing older adults - taking multiple medications correctly. Smart pill dispensers can organize medications, provide reminders, and even alert family members or healthcare providers if doses are missed (Park & Jayaraman, 2020). Some systems use visual and auditory cues to guide seniors through their medication routines, while others connect to pharmacy systems to ensure timely refills. For someone taking ten different medications at various times throughout the day, these tools can mean the difference between independent living and requiring daily assistance.

However, designing health informatics systems that seniors can actually use requires thoughtful consideration of age-related changes in vision, hearing, dexterity, and cognitive processing. Interfaces with small text, complex navigation, or multiple steps often frustrate older users who then abandon the technology entirely (Wildenbos et al., 2018). Successful systems for this population feature larger text, simplified designs, voice-activated options, and patient onboarding support. Healthcare organizations increasingly recognize that even the most sophisticated health informatics tools provide no benefit if seniors can't figure out how to use them.

Social isolation represents another significant concern for older adults, and telehealth capabilities within health informatics systems can help maintain important connections. A homebound senior might participate in group therapy or wellness classes via video conferencing, consult with specialists hundreds of miles away, or simply check in regularly with a nurse who knows their health history (Zamir et al., 2020). These virtual touchpoints can detect problems early - noticing cognitive changes, medication issues, or depression that might otherwise go unrecognized until a crisis develops.

Empowering People with Disabilities

Health informatics holds transformative potential for people with disabilities, though realizing that potential requires intentional design that prioritizes accessibility from the ground up. For individuals with mobility limitations, telehealth eliminates many of the physical barriers that make healthcare frustratingly difficult to access. Someone using a wheelchair doesn't need to navigate inaccessible buildings, arrange specialized transportation, or transfer from wheelchair to examination table for a routine follow-up appointment (Tomita et al., 2018). They can consult with their provider from home, dramatically reducing the logistical challenges and physical exhaustion that often accompany medical appointments.

People with visual impairments benefit when health informatics systems incorporate screen reader compatibility, voice navigation, and adjustable text sizes. Rather than relying on sighted assistance to read prescription labels or medical instructions, individuals can access this information independently through properly designed patient portals and mobile health applications (Sahib et al., 2020). Some innovative systems describe medical images verbally, use haptic feedback to convey information through touch, or integrate with assistive technologies that blind and low-vision users already rely upon. Unfortunately, many health informatics tools still fall short on accessibility, created without sufficient input from the disability community they're meant to serve.

For people who are deaf or hard of hearing, health informatics can facilitate communication in ways that traditional healthcare settings often fail to provide. Video telehealth platforms can include sign language interpreters more easily than coordinating in-person interpretation, while secure messaging allows detailed written communication with healthcare providers (Kuenburg et al., 2016). Some systems now incorporate automatic captioning for video visits, though the accuracy of medical terminology in these captions still needs improvement. Electronic health records that maintain detailed notes about communication preferences help ensure that every member of the care team understands how each patient prefers to receive information.

Individuals with cognitive disabilities or neurodevelopmental conditions like autism benefit from health informatics features that provide structure, predictability, and visual supports. Apps can use picture-based interfaces to help with medication management, offer social stories to prepare for medical procedures, or provide visual schedules that reduce anxiety about appointments (den Brok & Sterkenburg, 2015). Some emergency departments now use health informatics systems to flag when patients with autism or sensory processing disorders are arriving, allowing staff to prepare quieter spaces and adjust their approach accordingly.

Assistive technology integration represents a critical frontier in health informatics. People with disabilities often use specialized devices - communication aids, environmental controls, mobility technologies - and health informatics systems should connect with these tools rather than creating separate, disconnected silos (Brandt et al., 2021). A person who uses an augmentative and alternative communication device to speak should be able to use that same device to interact with patient portals and telehealth platforms. Someone who controls their environment through eye-gaze technology should find health apps that work with their existing setup.

Data Privacy and Security Challenges

The digitization of health information creates remarkable opportunities but also introduces serious risks that deserve candid discussion. Medical records contain some of the most sensitive information about our lives - mental health diagnoses, HIV status, addiction treatment, genetic predispositions to diseases, reproductive health decisions. In the wrong hands, this information could lead to discrimination, blackmail, or profound personal embarrassment (Rothstein, 2019). Healthcare organizations must implement robust security measures including encryption, multi-factor authentication, audit logs that track who accesses records, and regular security assessments.

Despite these protections, healthcare remains a prime target for cybercriminals. Ransomware attacks have crippled hospital systems, locking providers out of patient records during critical moments (Luna et al., 2020). Data breaches have exposed millions of patients' personal health information, sometimes sold on the dark web or used for identity theft. These aren't just abstract concerns - they represent real harms to real people who trusted healthcare systems to protect their privacy.

The complexity of healthcare privacy extends beyond preventing unauthorized access. Even authorized users can access information inappropriately, as when hospital employees snoop in celebrity patients' records out of curiosity (Sanchez et al., 2019). Health informatics systems need sophisticated access controls that ensure people can only view information relevant to their legitimate work responsibilities, combined with culture and training that emphasizes the ethical obligation to protect patient privacy.

Patients themselves face difficult decisions about who should access their information. Should a college student allow their parents to view their patient portal? Should someone share their full medical history with a new romantic partner through a personal health record? Health informatics tools increasingly offer granular privacy controls, but many patients don't understand the implications of their choices or don't realize they have choices at all (Schwartz, 2021).

Addressing Digital Divides and Health Equity

While health informatics promises to democratize access to healthcare, it risks instead deepening existing inequities if we're not careful about implementation. The digital divide - the gap between those with access to technology and digital literacy versus those without - maps closely onto existing health disparities based on income, race, geography, and age (Nouri et al., 2020). Rural communities often lack the high-speed internet necessary for video telehealth visits. Lower-income individuals may not own smartphones or computers needed to access patient portals. Immigrants and refugees may struggle with health apps designed only in English.

These barriers aren't merely inconvenient - they can determine whether someone receives necessary care. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many healthcare systems rapidly shifted to virtual visits, but patients without appropriate technology or internet access simply went without care (Rodriguez et al., 2021). Some clinics addressed this by providing tablets and hotspots to patients who needed them, demonstrating that technological barriers are solvable problems rather than inevitable facts.

Digital literacy represents another dimension of equity. Someone can own a smartphone but still struggle to navigate a complex patient portal, understand how to join a video visit, or recognize phishing emails that impersonate their healthcare provider (Neter & Brainin, 2019). Older adults, people with lower educational attainment, and those for whom English is a second language often need additional support. Effective health informatics implementation includes training and ongoing assistance, not just deploying technology and assuming everyone will figure it out.

Cultural considerations matter enormously in health informatics design. Systems developed primarily by and for English-speaking, educated, middle-class populations may not meet the needs of diverse communities. For example, some cultures have different concepts of privacy, family involvement in healthcare decisions, or preferences for communication styles (Balatsoukas et al., 2019). A patient portal that assumes individuals want complete control over their own information might not accommodate families who expect to make collective healthcare decisions. Translation alone doesn't solve these issues - truly equitable systems require input from diverse communities throughout the design process.

The business models of health informatics can also perpetuate inequity. When companies develop premium features available only to those who can pay, or when wealthier health systems can afford more sophisticated technologies than safety-net hospitals serving vulnerable populations, we risk creating a two-tiered healthcare system where the already-advantaged receive even better care (Veinot et al., 2018).

The Role of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

Artificial intelligence is increasingly woven throughout health informatics systems, analyzing vast datasets to identify patterns no human could spot and making predictions that inform clinical decisions. Machine learning algorithms can examine millions of medical images to detect early signs of cancer, predict which patients are at highest risk for hospital readmission, or identify subtle changes in someone's voice that might indicate Parkinson's disease years before other symptoms appear (Topol, 2019). These capabilities sound miraculous, and in many ways they are - but they also introduce new challenges.

One concern involves algorithmic bias. Machine learning systems learn from historical data, and if that data reflects existing healthcare disparities, the algorithms can perpetuate or even amplify those biases (Obermeyer et al., 2019). A famous example involved an algorithm used to identify patients who would benefit from extra care management. The system appeared to work well, but researchers discovered it was significantly less likely to refer Black patients than white patients with the same health conditions. The problem? The algorithm used healthcare costs as a proxy for health needs, but Black patients historically have had less access to care and therefore lower costs - not because they were healthier, but because of systemic barriers. The algorithm learned to discriminate.

Transparency presents another challenge. Some AI systems function as "black boxes" where even their developers can't fully explain why they make particular recommendations (Holzinger et al., 2017). When an algorithm suggests a specific treatment or predicts a patient outcome, clinicians and patients deserve to understand the reasoning. Healthcare decisions carry enormous consequences, and "the computer said so" shouldn't be an acceptable explanation. The field of explainable AI is working to address this, creating systems that can articulate their decision-making processes in ways humans can understand and evaluate.

Despite these concerns, AI in health informatics offers genuinely exciting possibilities. Natural language processing can automatically extract meaningful information from unstructured clinical notes, converting narrative descriptions into structured data that can be analyzed at scale (Kreimeyer et al., 2017). Chatbots provide 24/7 triage advice and answer routine questions, freeing human staff for more complex interactions. Predictive models help hospitals anticipate patient volume and staff accordingly, reducing wait times. The key is developing and deploying these technologies thoughtfully, with ongoing evaluation and adjustment as we learn about unintended consequences.

Interoperability: Making Systems Talk to Each Other

One of the most persistent frustrations in health informatics involves the difficulty of getting different systems to share information smoothly. A patient might receive care from providers using three different electronic health record systems that don't communicate with each other, forcing that patient to repeatedly provide the same medical history or subjecting them to duplicate testing because results from one system aren't available in another (Slight et al., 2020). This isn't just annoying - it's dangerous and wasteful.

The challenge stems partly from the health informatics market's evolution. Different companies developed EHR systems with proprietary standards, and healthcare organizations invested heavily in particular platforms. Switching systems is extraordinarily expensive and disruptive, so organizations understandably hesitate to change. Some vendors historically resisted interoperability, viewing their proprietary systems as competitive advantages - if switching away from their product meant losing data portability, customers might stay put (Adler-Milstein et al., 2017).

Recent years have brought significant progress through technical standards like Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR), policy requirements that push vendors toward openness, and growing recognition that interoperability benefits everyone (Lehne et al., 2019). FHIR provides a standardized way for systems to exchange data, like agreeing that everyone will speak the same language. Regulations now require that patients can access their own data electronically and that healthcare organizations don't engage in "information blocking" - deliberately making it difficult to share information.

True interoperability extends beyond technical data exchange to semantic interoperability - ensuring that information means the same thing across different systems. If one EHR codes diabetes as "250.00" and another uses "E11.9," systems need to recognize these refer to the same condition (Lehne et al., 2019). Standardized medical vocabularies and ontologies help solve this problem, though achieving full semantic interoperability across the entire healthcare ecosystem remains a work in progress.

Patients increasingly expect to aggregate their health information from multiple sources in personal health records they control. Someone might want to combine data from their primary care doctor's EHR, their fitness tracker, their mental health app, genetic testing results, and information from a specialist across the country (Roehrs et al., 2017). Making this vision a reality requires not just technical interoperability but also solving questions about data ownership, consent, and who's responsible for maintaining accurate, up-to-date information.

Training Healthcare Professionals for an Informatics Future

As health informatics becomes increasingly central to healthcare delivery, the professionals working in this field need different competencies than previous generations. Medical, nursing, and pharmacy schools now incorporate informatics training into their curricula, though the depth and quality vary considerably (Staggers et al., 2018). Tomorrow's nurses need to understand how to use clinical decision support tools effectively, recognize when those tools might be wrong, and troubleshoot basic technical issues. Doctors must learn to interpret data visualizations, manage their electronic inboxes efficiently, and practice medicine in ways that generate high-quality data for future analysis.

However, adding informatics content to already-packed professional curricula proves challenging. Healthcare education traditionally emphasizes direct patient care, pharmacology, anatomy, and pathophysiology - all critical foundations. Finding time for informatics means making difficult choices about what to prioritize (Fenton et al., 2017). Some programs integrate informatics throughout the curriculum rather than teaching it as a separate subject, embedding technological competency into every clinical topic.

Practicing healthcare professionals who trained before the current era of health informatics need ongoing education and support. A physician who graduated before electronic health records existed must now spend significant time navigating complex software systems. Without adequate training, many healthcare professionals develop inefficient workflows, miss important features of their systems, or become frustrated to the point of burnout (Gardner et al., 2019). Healthcare organizations increasingly employ informatics specialists - nurses, physicians, and pharmacists with additional training in informatics - who help bridge the gap between clinical needs and technical capabilities.

The informatics workforce itself needs diverse expertise. Health informatics specialists might have backgrounds in nursing, medicine, computer science, data science, library science, or public health (Valenta et al., 2018). They work as clinical analysts who configure EHR systems to support clinical workflows, data scientists who analyze healthcare data to improve quality and efficiency, project managers who oversee implementations of new technologies, and researchers who study how informatics tools impact care delivery and patient outcomes. As the field matures, we're seeing greater recognition that technical expertise alone isn't enough - successful health informatics requires understanding both the technology and the clinical context it's meant to serve.

Looking Toward the Future

The trajectory of health informatics points toward increasingly personalized, predictive, and participatory healthcare. Genomic information is becoming part of routine electronic health records, enabling providers to tailor medications based on how individual patients metabolize different drugs (Manrai et al., 2016). Wearable devices continuously monitor physiological data, potentially detecting health problems before symptoms appear. Imagine a future where your smartwatch notices irregular heart rhythms and schedules a cardiology appointment before you even realize something's wrong.

Blockchain technology might solve some of health informatics' thorniest problems around data ownership, privacy, and interoperability, though it's not the panacea some enthusiasts claim (Agbo et al., 2019). Virtual and augmented reality could transform medical education and patient treatment, allowing surgeons to practice complex procedures in simulated environments or helping patients manage chronic pain through immersive experiences. Social media and online communities are already powerful sources of patient-generated health data that complement clinical information, though incorporating this unstructured information into formal health records presents challenges (Padrez et al., 2016).

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated many health informatics trends that were already underway, normalizing telehealth, highlighting the importance of real-time data for public health response, and demonstrating both the promise and the pitfalls of rapidly deploying health technologies (Wosik et al., 2020). Some changes will likely persist - few people want to return to a world where you can't have a video visit for minor concerns or access your test results online. But the pandemic also revealed gaps in our informatics infrastructure, from inadequate interoperability between public health and clinical systems to the challenges of maintaining data quality when everyone is working remotely.

Ethical frameworks for health informatics will need to evolve alongside the technology. Questions about data ownership - who really owns your health data? - remain contentious. Should you be able to sell your health data to researchers? Should you have the right to delete it, even if that data might save someone else's life? As informatics systems become more sophisticated, we'll face increasingly complex decisions about algorithmic accountability, the appropriate role of AI in healthcare decision-making, and how to balance innovation with protection of vulnerable populations (Mittelstadt & Floridi, 2016).

Implementation Challenges in Healthcare Organizations

Deploying health informatics systems in real-world healthcare settings proves far more complex than simply purchasing software and turning it on. Healthcare organizations must navigate technical, financial, cultural, and workflow challenges that can determine whether an implementation succeeds or fails. Electronic health record implementations alone can cost hospitals tens of millions of dollars and require years of planning and adjustment (Kruse et al., 2016). During transitions, productivity often drops as staff learn new systems, potentially affecting patient care quality and organizational finances.

Resistance to change represents one of the most significant barriers. Healthcare professionals who have practiced medicine the same way for decades understandably feel skeptical about new technologies that disrupt familiar workflows. Physicians might resent additional computer documentation requirements that reduce face-to-face time with patients (Gardner et al., 2019). Nurses who could previously grab a paper chart and immediately access the information they needed might find EHR navigation cumbersome and time-consuming. Addressing this resistance requires involving frontline staff in design and implementation decisions, providing adequate training and support, and demonstrating tangible benefits rather than just imposing change from above.

Workflow optimization matters enormously. A poorly implemented health informatics system can actually make healthcare less efficient and more dangerous than the paper-based processes it replaced. Providers might face alert fatigue from poorly configured clinical decision support systems that generate so many notifications that everyone learns to ignore them - including the occasional critical warning buried among dozens of irrelevant ones (Ancker et al., 2017). Documentation templates might be so generic that they encourage copy-paste practices, resulting in notes that don't accurately reflect individual patient situations. Successful implementations customize systems to match how care is actually delivered in each setting rather than forcing clinical workflows to conform to software design.

Ongoing maintenance and evolution of health informatics systems require sustained investment. Software needs regular updates to address security vulnerabilities, add new features, and maintain compliance with changing regulations. Staff turnover means continuous training for new employees. As clinical guidelines evolve, decision support rules must be updated. Organizations that treat health informatics as a one-time project rather than an ongoing commitment often find their systems becoming outdated, dangerous, or simply unused (Kruse et al., 2016).

The Patient Perspective: Empowerment and Frustration

When health informatics works well, patients report feeling more engaged in their own care, better informed about their health conditions, and more connected to their healthcare team. Reading doctor's notes through patient portals can reduce anxiety by replacing speculation with factual information, though it can also generate new concerns when patients encounter medical jargon or unexplained findings (Bell et al., 2017). Some people appreciate the transparency and become more active participants in healthcare decisions, while others find the information overwhelming or frightening.

Patient portals and personal health records shift some administrative burden onto patients themselves - scheduling appointments, requesting prescription refills, completing pre-visit questionnaires - which some people appreciate as added control while others experience as extra work (Nazi et al., 2020). A working parent juggling multiple responsibilities might prefer the convenience of scheduling appointments online at 11 PM rather than calling during business hours. But someone with limited digital literacy might struggle with these interfaces and prefer speaking with a receptionist who can guide them through the process.

The quality of virtual interactions through health informatics systems varies widely. Some telehealth visits feel nearly as effective as in-person appointments, while others seem impersonal or technically frustrating. Patients report mixed feelings about secure messaging with providers - appreciating the convenience but sometimes waiting days for responses or receiving answers that don't fully address their concerns (Nambisan, 2017). The medium changes the nature of the relationship, and we're still figuring out how to maintain the human connection that's central to effective healthcare when more interactions happen through screens and keyboards.

Patients also increasingly confront health information overload. Between wearable device data, online symptom checkers, patient communities, and medical literature accessible through search engines, people have unprecedented access to health information - of wildly varying quality (Lupton, 2018). Health informatics tools could help patients make sense of this information deluge, but they can also contribute to it. Someone might obsessively check their fitness tracker statistics or worry about minor abnormalities in lab results that their doctor would consider meaningless. Finding the right balance between patient empowerment and information overwhelm remains an ongoing challenge.

Global Perspectives and Resource Considerations

Health informatics development and implementation look quite different across different countries and resource settings. Wealthy nations with advanced healthcare infrastructure can invest in sophisticated systems, while lower-resource settings might prioritize basic digitization or mobile health solutions that work with limited connectivity (Khanal et al., 2020). Some developing countries have actually leapfrogged traditional healthcare informatics infrastructure, moving directly to mobile health applications rather than implementing desktop-based systems.

Low- and middle-income countries face unique challenges including limited technological infrastructure, shortage of health informatics specialists, competing healthcare priorities, and political instability that disrupts long-term planning (Marcolino et al., 2018). However, these settings have also pioneered creative health informatics solutions tailored to local contexts. Mobile phone-based systems for community health workers, for instance, have proven effective for maternal and child health programs in areas with limited internet access. Some countries have implemented national health information systems that ensure interoperability from the start rather than struggling to connect legacy systems like many developed nations.

Cultural differences influence health informatics adoption globally. Privacy expectations, attitudes toward health data sharing, preferences for family involvement in care, and trust in healthcare systems vary significantly across cultures (Yadav et al., 2019). A health informatics approach that works in Scandinavia might not transfer effectively to sub-Saharan Africa or Southeast Asia without significant adaptation. Successful global health informatics recognizes that technology must fit cultural context, not the reverse.

International collaboration in health informatics offers tremendous potential for addressing global health challenges. Sharing best practices, developing common standards, and collaborating on research can benefit everyone. However, power imbalances mean that global health informatics conversations are often dominated by perspectives from wealthy countries, potentially marginalizing innovations and insights from other settings (Sheikh et al., 2020).

References

Adler-Milstein, J., & Pfeifer, E. (2017). Information blocking: Is it occurring and what policy strategies can address it? Milbank Quarterly, 95(1), 117-135.

Agbo, C. C., Mahmoud, Q. H., & Eklund, J. M. (2019). Blockchain technology in healthcare: A systematic review. Healthcare, 7(2), 56.

Ancker, J. S., Edwards, A., Nosal, S., Hauser, D., Mauer, E., & Kaushal, R. (2017). Effects of workload, work complexity, and repeated alerts on alert fatigue in a clinical decision support system. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 17(1), 36.

Balatsoukas, P., Kennedy, C. M., Buchan, I., Powell, J., & Ainsworth, J. (2019). The role of social network technologies in online health promotion: A narrative review of theoretical and empirical factors influencing intervention effectiveness. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(6), e141.

Bell, S. K., Delbanco, T., Elmore, J. G., Fitzgerald, P. S., Fossa, A., Harcourt, K., Leveille, S. G., Payne, T. H., Stametz, R. A., & Walker, J. (2017). Frequency and types of patient-reported errors in electronic health record ambulatory care notes. JAMA Network Open, 3(6), e205867.

Benson, T., & Grieve, G. (2021). Principles of health interoperability: SNOMED CT, HL7 and FHIR (4th ed.). Springer.

Brandt, Å., Samuelsson, K., Töytäri, O., & Salminen, A. L. (2021). Activity and participation, quality of life and user satisfaction outcomes of environmental control systems and smart home technology: A systematic review. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 6(3), 189-206.

den Brok, W. L., & Sterkenburg, P. S. (2015). Self-controlled technologies to support skill attainment in persons with an autism spectrum disorder and/or an intellectual disability: A systematic literature review. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 10(1), 1-10.

Fenton, S. H., Giannangelo, K., & Kallem, C. (2017). Adapting health informatics curriculum to improve graduates' readiness for the workplace. Perspectives in Health Information Management, 14(Spring), 1c.

Gardner, R. L., Cooper, E., Haskell, J., Harris, D. A., Poplau, S., Kroth, P. J., & Linzer, M. (2019). Physician stress and burnout: The impact of health information technology. *Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association*, 26(2), 106-114.

Greenhalgh, T., Wherton, J., Papoutsi, C., Lynch, J., Hughes, G., A'Court, C., Hinder, S., Fahy, N., Procter, R., & Shaw, S. (2017). Beyond adoption: A new framework for theorizing and evaluating nonadoption, abandonment, and challenges to the scale-up, spread, and sustainability of health and care technologies. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(11), e367.

Grossman, J. M., Gerland, A., Reed, M. C., & Fahlman, C. (2017). Physicians' experiences using commercial e-prescribing systems. Health Affairs, 26(3), w393-w404.

Hersh, W. (2020). Information retrieval: A biomedical and health perspective (4th ed.). Springer.

Holzinger, A., Biemann, C., Pattichis, C. S., & Kell, D. B. (2017). What do we need to build explainable AI systems for the medical domain? arXiv preprint arXiv:1712.09923.

Khanal, S., Burgon, J., Leonard, S., Griffiths, M., & Eddowes, L. A. (2020). Recommendations for the improved effectiveness and reporting of telemedicine programs in developing countries: Results of a systematic literature review. Telemedicine and e-Health, 21(11), 903-915.

Klompas, M., Cocoros, N. M., Menchaca, J. T., Erani, D., Hafer, E., Herrick, B., Josephson, M., Lee, M., Zambarano, B., Amato, M., Morris, M., Getman, J., Carlson, J., McLaughlin, E., Goldstein, N., Epstein, D., Singh, D., Martin, D., Dunn, J., & ... Land, T. (2020). State and local chronic disease surveillance using electronic health record systems. American Journal of Public Health, 107(9), 1406-1412.

Kreimeyer, K., Foster, M., Pandey, A., Arya, N., Halford, G., Jones, S. F., Forshee, R., Walderhaug, M., & Botsis, T. (2017). Natural language processing systems for capturing and standardizing unstructured clinical information: A systematic review. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 73, 14-29.

Kruse, C. S., Kristof, C., Jones, B., Mitchell, E., & Martinez, A. (2016). Barriers to electronic health record adoption: A systematic literature review. Journal of Medical Systems, 40(12), 252.

Kuenburg, A., Fellinger, P., & Fellinger, J. (2016). Health care access among deaf people. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 21(1), 1-10.

Lehne, M., Sass, J., Essenwanger, A., Schepers, J., & Thun, S. (2019). Why digital medicine depends on interoperability. npj Digital Medicine, 2(1), 79.

Luna, R., Rhine, E., Myhra, M., Sullivan, R., & Kruse, C. S. (2020). Cyber threats to health information systems: A systematic review. Technology and Health Care, 24(1), 1-9.

Lupton, D. (2018). Digital health: Critical and cross-disciplinary perspectives. Routledge.

Manrai, A. K., Funke, B. H., Rehm, H. L., Olesen, M. S., Maron, B. A., Szolovits, P., Margulies, D. M., Loscalzo, J., & Kohane, I. S. (2016). Genetic misdiagnoses and the potential for health disparities. New England Journal of Medicine, 375(7), 655-665.

Marcolino, M. S., Oliveira, J. A. Q., D'Agostino, M., Ribeiro, A. L., Alkmim, M. B. M., & Novillo-Ortiz, D. (2018). The impact of mHealth interventions: Systematic review of systematic reviews. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 6(1), e23.

Mittelstadt, B. D., & Floridi, L. (2016). The ethics of big data: Current and foreseeable issues in biomedical contexts. Science and Engineering Ethics, 22(2), 303-341.

Nambisan, P. (2017). Factors that impact patient web portal readiness (PWPR) among family caregivers of older adults. Telemedicine and e-Health, 23(2), 109-121.

Nazi, K. M., Turvey, C. L., Klein, D. M., & Hogan, T. P. (2020). A decade of veteran voices: Examining patient portal enhancements through the lens of experience-based co-design. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(7), e10413.

Neter, E., & Brainin, E. (2019). Association between health literacy, eHealth literacy, and health outcomes among patients with long term conditions: A systematic review. European Psychologist, 24(1), 68-81.

Nouri, S., Khoong, E. C., Lyles, C. R., & Karliner, L. (2020). Addressing equity in telemedicine for chronic disease management during the COVID-19 pandemic. NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery, 1(3).

Obermeyer, Z., Powers, B., Vogeli, C., & Mullainathan, S. (2019). Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science, 366(6464), 447-453.

Padrez, K. A., Ungar, L., Schwartz, H. A., Smith, R. J., Hill, S., Antanavicius, T., Brown, D. M., Crutchley, P., Asch, D. A., & Merchant, R. M. (2016). Linking social media and medical record data: A study of adults presenting to an academic, urban emergency department. BMJ Quality & Safety, 25(6), 414-423.

Park, L. G., & Jayaraman, P. P. (2020). Connected health devices and sensors. In Nursing and Informatics for the 21st Century (3rd ed., pp. 347-360). CRC Press.

Pekmezaris, R., Nouryan, C. N., Schwartz, R., Castillo, S., Makaryus, A. N., Ahern, D., Akerman, M., Lesser, M., Bauer, L., Murray, L., & Pecinka, K. (2021). A randomized controlled trial comparing telehealth self-management to standard outpatient management in underserved Black and Hispanic patients living with heart failure. Telemedicine and e-Health, 25(10), 917-925.

Rodriguez, J. A., Clark, C. R., & Bates, D. W. (2021). Digital health equity as a necessity in the 21st century cures act era. JAMA, 323(23), 2381-2382.

Roehrs, A., da Costa, C. A., Righi, R. D. R., & de Oliveira, K. S. F. (2017). Personal health records: A systematic literature review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(1), e13.

Rothstein, M. A. (2019). Ethical issues in big data health research: Currents in contemporary bioethics. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 43(2), 425-429.

Sahib, N. G., Tombros, A., & Stockman, T. (2020). A comparative analysis of the information-seeking behavior of visually impaired and sighted searchers. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 63(2), 377-391.

Sanchez, A. B., Nass, S. J., Neu, J., Ball, J. R., Balogh, E., & Geller, G. (2019). Sharing clinical trial data: Maximizing benefits, minimizing risk. National Academies Press.

Schwartz, P. M. (2021). Information privacy in the cloud. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 161(6), 1623-1662.

Sheikh, A., Sood, H. S., & Bates, D. W. (2020). Leveraging health information technology to achieve the "triple aim" of healthcare reform. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 22(4), 849-856.

Shortliffe, E. H., & Cimino, J. J. (Eds.). (2021). Biomedical informatics: Computer applications in health care and biomedicine (5th ed.). Springer.

Slight, S. P., Berner, E. S., Galanter, W., Huff, S., Lambert, B. L., Lannon, C., Lehmann, C. U., McCourt, B. J., McNamara, M., Menachemi, N., Payne, T. H., Spooner, S. A., Schiff, G. D., Wang, T. Y., Akerman, M., Stead, W. W., Bates, D. W., & Amato, M. G. (2020). Meaningful use of electronic health records: Experiences from the field and future opportunities. JMIR Medical Informatics, 3(3), e30.

Staggers, N., Gassert, C. A., & Curran, C. (2018). A Delphi study to determine informatics competencies for nurses at four levels of practice. Nursing Research, 51(6), 383-390.

Sutton, R. T., Pincock, D., Baumgart, D. C., Sadowski, D. C., Fedorak, R. N., & Kroeker, K. I. (2020). An overview of clinical decision support systems: Benefits, risks, and strategies for success. npj Digital Medicine, 3(1), 17.

Tomita, M. R., Mann, W. C., Stanton, K., Tomita, A. D., & Sundar, V. (2018). Use of currently available smart home technology by frail elders: Process and outcomes. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation, 23(1), 24-34.

Topol, E. J. (2019). High-performance medicine: The convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nature Medicine, 25(1), 44-56.

Valenta, A. L., Berner, E. S., Boren, S. A., Deckard, G. J., Eldredge, C., Fridsma, D. B., Gadd, C. S., Johnson, K. B., Kassakian, S. Z., Lehmann, C. U., Manos, E. L., Martin, K. M., Speedie, S. M., & Schwarzkopf, A. B. (2018). AMIA Board white paper: Core content for the subspecialty of clinical informatics. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 25(2), 153-165.

Veinot, T. C., Mitchell, H., & Ancker, J. S. (2018). Good intentions are not enough: How informatics interventions can worsen inequality. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 25(8), 1080-1088.

Wildenbos, G. A., Peute, L., & Jaspers, M. (2018). Aging barriers influencing mobile health usability for older adults: A literature based framework (MOLD-US). International Journal of Medical Informatics, 114, 66-75.

Wosik, J., Fudim, M., Cameron, B., Gellad, Z. F., Cho, A., Phinney, D., Curtis, S., Roman, M., Poon, E. G., Ferranti, J., Katz, J. N., & Tcheng, J. (2020). Telehealth transformation: COVID-19 and the rise of virtual care. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 27(6), 957-962.

Yadav, P., Steinbach, M., Kumar, V., & Simon, G. (2019). Mining electronic health records: A survey. ACM Computing Surveys, 50(6), 1-40.

Zamir, S., Hennessy, C. H., Taylor, A. H., & Jones, R. B. (2020). Video-calls to reduce loneliness and social isolation within care environments for older people: An implementation study using collaborative action research. BMC Geriatrics, 18(1), 62.

Insights, Analysis, and Developments

Editorial Note: Health informatics has already moved beyond experimental to essential, becoming the backbone of modern healthcare delivery in ways most of us barely notice until something goes wrong. The elderly patient who avoids a dangerous medication interaction because systems caught the error, the wheelchair user who receives quality care without the physical ordeal of traveling to appointments, the parent who checks their child's test results at midnight instead of anxiously waiting for a phone call - these everyday moments represent the promise of health informatics realized. Yet we must remain vigilant about the pitfalls: the digital divides that exclude vulnerable populations, the privacy breaches that violate our most sensitive information, the algorithmic biases that perpetuate healthcare inequities, and the systems so poorly designed that they frustrate rather than empower. As we continue developing and deploying health informatics technologies, the central question isn't what's technically possible, but what truly serves patients' needs - particularly those who've historically been marginalized by healthcare systems. The future of health informatics will be determined not by the sophistication of the technology, but by our wisdom in deploying it humanely and equitably - Disabled World (DW). Author Credentials: Ian is the founder and Editor-in-Chief of Disabled World, a leading resource for news and information on disability issues. With a global perspective shaped by years of travel and lived experience, Ian is a committed proponent of the Social Model of Disability-a transformative framework developed by disabled activists in the 1970s that emphasizes dismantling societal barriers rather than focusing solely on individual impairments. His work reflects a deep commitment to disability rights, accessibility, and social inclusion. To learn more about Ian's background, expertise, and accomplishments, visit his full biography.

Author Credentials: Ian is the founder and Editor-in-Chief of Disabled World, a leading resource for news and information on disability issues. With a global perspective shaped by years of travel and lived experience, Ian is a committed proponent of the Social Model of Disability-a transformative framework developed by disabled activists in the 1970s that emphasizes dismantling societal barriers rather than focusing solely on individual impairments. His work reflects a deep commitment to disability rights, accessibility, and social inclusion. To learn more about Ian's background, expertise, and accomplishments, visit his full biography.