Translational Medicine: Bridging Research and Real Care

Author: Ian C. Langtree - Writer/Editor for Disabled World (DW)

Published: 2026/01/24

Publication Type: Scholarly Paper

Category Topic: Journals - Papers - Related Publications

Page Content: Synopsis - Introduction - Main - Insights, Updates

Synopsis: Medical breakthroughs mean nothing if they never reach the people who need them most. This fundamental truth drives the fields of translational medicine and translational development - two complementary approaches that have reshaped how we think about healthcare innovation. While laboratories around the world make remarkable discoveries daily, the real challenge lies in transforming those discoveries into treatments that improve lives, particularly for vulnerable populations like seniors and people with disabilities. These fields represent not just a scientific methodology but a philosophical commitment: that research should serve people, not just advance knowledge for its own sake. In the paper that follows, we'll explore how translational approaches are revolutionizing healthcare delivery, breaking down barriers that have historically prevented medical advances from reaching those who could benefit most, and why this matters profoundly for the aging population and disability community - Disabled World (DW).

Introduction

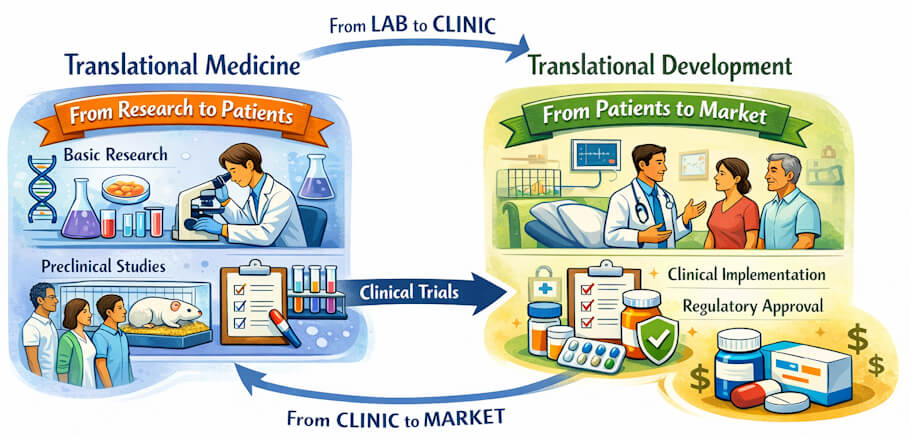

Defining Translational Medicine and Translational Development

Translational Medicine:

Translational medicine is the scientific discipline dedicated to improving human health by converting laboratory discoveries and research findings into practical medical applications that directly benefit patients. The term captures the essential act of "translating" or transforming basic scientific knowledge - the kind generated in research laboratories studying cells, molecules, genes, and disease mechanisms - into diagnostic tests, treatments, and preventive strategies that doctors can use and patients can access. What distinguishes translational medicine from traditional research is its explicit, intentional focus on application and impact.

Rather than conducting research for the sake of advancing knowledge alone, translational medicine begins with clinical needs and works systematically to address them, creating a bidirectional flow of information between laboratory scientists and clinical practitioners. This approach recognizes that the most elegant scientific discovery holds little value if it never leaves the research environment to improve actual patient outcomes. The field emerged in response to the troubling realization that despite massive investments in biomedical research, relatively few discoveries were making their way into routine clinical practice, and those that did often took decades to arrive.

Translational medicine seeks to accelerate and improve this process, creating deliberate pathways that move promising findings through the stages of development, testing, and implementation more efficiently while maintaining rigorous safety and efficacy standards. It requires collaboration across traditional boundaries, bringing together basic scientists, clinical researchers, healthcare providers, patients, regulatory experts, and others in a shared mission to transform scientific potential into health improvements.

Translational Development:

Translational development encompasses the broader ecosystem of activities, infrastructure, and strategies required to ensure that medical innovations successfully move from research settings into widespread, equitable, and sustainable use in real-world healthcare environments. While translational medicine focuses primarily on the scientific and clinical aspects of moving from discovery to treatment, translational development addresses the complex web of additional factors that determine whether an innovation actually improves health outcomes at the population level. This includes the practical challenges of manufacturing treatments at scale while maintaining quality, developing delivery systems that can reach diverse patient populations, creating business and payment models that make innovations financially sustainable and accessible, training healthcare providers to use new tools and approaches effectively, educating patients about new options, addressing regulatory requirements across different jurisdictions, and overcoming social, cultural, and structural barriers to adoption.

Translational development recognizes that healthcare operates within complex systems where scientific excellence alone cannot guarantee success - an innovative treatment fails if patients cannot afford it, if providers don't know how to prescribe it properly, if it requires infrastructure that doesn't exist in certain communities, or if cultural factors prevent its acceptance. The field draws on diverse disciplines including health economics, implementation science, health services research, medical education, health policy, communications, and community engagement.

For seniors and people with disabilities, translational development is particularly crucial because these populations often face multiple, overlapping barriers to accessing healthcare innovations, from physical accessibility challenges and financial constraints to provider knowledge gaps and societal attitudes that undervalue their health needs. Effective translational development ensures that when medical science offers new possibilities, the practical pathways exist for those possibilities to reach everyone who could benefit, regardless of age, ability, geography, or economic circumstances.

Main Content

Understanding Translational Medicine: Bridging the Research Gap

Translational medicine represents one of the most significant shifts in how we approach healthcare in the modern era. At its core, this field seeks to bridge the gap between laboratory discoveries and practical treatments that improve patient outcomes. The concept emerged from a growing frustration within the scientific community during the late 20th century - researchers were making remarkable discoveries about disease mechanisms, yet these insights often languished in academic journals without ever reaching the patients who desperately needed them (Woolf, 2008).

The traditional pathway from basic science to clinical application was notoriously inefficient. Studies have shown that it takes an average of 17 years for research evidence to reach clinical practice, and even then, only about 14% of original discoveries make it through to patient care (Balas & Boren, 2000). This lengthy timeline meant that patients were missing out on potentially life-saving treatments while researchers continued publishing papers that gathered dust on library shelves.

The Translation Spectrum: From Laboratory to Patient

Translational medicine aims to dismantle these barriers by creating a more direct pipeline between the laboratory bench and the patient's bedside. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) describes this process using a framework called the "T spectrum," which includes multiple stages of translation (Rubio et al., 2010). T0 represents basic scientific discoveries, while T1 focuses on developing these findings into potential treatments. T2 involves testing these treatments in clinical trials, T3 examines how to implement proven treatments in real-world healthcare settings, and T4 looks at population-level health outcomes.

Consider how this works in practice. A molecular biologist might discover that a particular protein plays a crucial role in the development of Alzheimer's disease. In a traditional research environment, this finding would be published and perhaps cited by other scientists, but the path to creating an actual drug targeting that protein could take decades - if it happened at all. Translational medicine changes this dynamic by intentionally designing research programs that include clinical partners from the beginning. The molecular biologist works alongside neurologists, pharmacologists, and even patients to ensure the research moves systematically toward a practical application.

Translational Development: The Broader Context

Translational development, while closely related to translational medicine, takes a somewhat broader view of the challenge. This field recognizes that creating an effective treatment is only part of the equation. Even the most brilliant medical innovation fails if it cannot be manufactured affordably, distributed efficiently, delivered appropriately, or accepted by the communities it aims to serve (Khoury et al., 2007).

The distinction becomes clearer when we examine real-world examples. Translational medicine might successfully develop a new injectable medication that reduces the progression of multiple sclerosis. Translational development then asks the harder questions: Can patients afford this medication? Do healthcare providers have the training to administer it properly? Are there cultural or logistical barriers preventing certain populations from accessing it? How do we educate patients about its benefits and risks in language they can understand?

The Unique Challenges Facing Seniors in Medical Research

For seniors and individuals with disabilities, both translational medicine and translational development hold particular promise and present unique challenges. Older adults have historically been underrepresented in clinical trials, despite being the primary consumers of healthcare services and medications (Witham & George, 2014). This creates a troubling paradox where drugs are approved based on studies of younger, healthier populations and then prescribed to elderly patients who may respond very differently.

The reasons for excluding seniors from research are varied but often misguided. Researchers sometimes worry about the complexity of studying people who have multiple health conditions or who take multiple medications - yet these are precisely the patients who will ultimately use the treatments being developed. Age-related changes in metabolism, kidney function, and drug sensitivity mean that a medication perfectly safe for a 35-year-old might cause serious problems in a 75-year-old (Mangoni & Jackson, 2004).

Translational medicine is beginning to address this gap by specifically designing studies that include diverse age groups and that account for the realities of aging bodies. For instance, research into osteoporosis treatments now routinely includes participants in their 70s and 80s, recognizing that this is the population most affected by the condition. Similarly, cancer research has expanded to include more elderly participants, leading to important discoveries about how older adults respond to chemotherapy and immunotherapy treatments (Hurria et al., 2016).

Disability Research: From Exclusion to Inclusion

The application of translational principles to disability research has been equally transformative. Historically, people with disabilities were often excluded from medical research under the paternalistic assumption that participation might be too difficult or risky for them. This exclusion perpetuated a cycle where medical treatments were developed without input from the very people they were meant to help (Weise et al., 2020).

Modern translational approaches prioritize the inclusion of people with disabilities throughout the research process. This means not just recruiting them as study participants, but involving them in designing the research questions, determining outcome measures, and interpreting results. A study developing a new assistive technology for people with mobility impairments, for example, would include wheelchair users on the research team to ensure the technology addresses real needs rather than what researchers assume the needs might be.

The Principle of "Nothing About Us Without Us"

The concept of "nothing about us without us" has become a guiding principle in disability-related translational research (Charlton, 1998). This phrase, which originated in the disability rights movement, emphasizes that research should be conducted with people with disabilities rather than on them. When individuals with lived experience of disability help shape research priorities, the resulting innovations are more likely to address actual barriers and improve quality of life in meaningful ways.

Consider the development of brain-computer interfaces for people with severe paralysis. Early research focused primarily on the technical feasibility of allowing people to control computers or robotic limbs with their thoughts. While scientifically impressive, these early systems often failed to account for practical considerations like the time required for daily setup, the mental fatigue of using the system, or whether the tasks the system enabled were actually priorities for users (Blabe et al., 2015).

More recent translational approaches to this technology have involved people with paralysis from the earliest design stages. These individuals have helped researchers understand that being able to check email independently or adjust the thermostat in their home might be more valuable than controlling a robotic arm, even if the latter seems more technologically advanced. This input has fundamentally reshaped research priorities and led to more practical applications.

Social Determinants of Health and Access Barriers

The translational development framework becomes especially critical when we consider the social determinants of health that affect seniors and people with disabilities. Even when effective treatments exist, multiple barriers can prevent these populations from accessing them. Transportation challenges, fixed incomes, caregiver availability, health literacy, and physical accessibility of healthcare facilities all play crucial roles in whether a scientific breakthrough actually improves someone's life (Iezzoni & O'Day, 2006).

A powerful example of translational development in action involves the treatment of age-related macular degeneration, a leading cause of vision loss in older adults. Researchers developed highly effective medications that, when injected into the eye, can preserve or even restore vision. From a pure translational medicine perspective, this was a tremendous success. However, translational development research revealed significant barriers to actually delivering this treatment (Cohen et al., 2010).

Many elderly patients had difficulty getting to monthly injection appointments, especially if they lived in rural areas or had limited family support. The cost of the medication and the procedures created financial hardship for some. Others felt anxious about the idea of injections into the eye, even though the procedure is performed under local anesthesia. Translational development efforts focused on addressing these barriers - developing systems for patient transportation, creating financial assistance programs, improving patient education materials, and exploring less frequent dosing schedules.

Gerontechnology: Technology Serving Older Adults

The field of gerontechnology provides another compelling illustration of how translational medicine and development intersect for seniors. This discipline applies translational principles to create technologies that help older adults maintain independence and quality of life. Smart home systems that can detect falls, medication dispensers that provide reminders and prevent errors, and telehealth platforms that reduce the need for travel all emerged from translational research programs (Peek et al., 2014).

However, simply creating these technologies is insufficient. Translational development research has shown that older adults often face barriers in adopting new technologies, including concerns about privacy, difficulty learning new systems, and costs. Successful implementation requires addressing these concerns through user-friendly design, comprehensive training programs, and business models that make the technology affordable and accessible.

Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically illustrated both the potential and the challenges of translational medicine and development for vulnerable populations. The unprecedented speed at which effective vaccines were developed demonstrated what translational medicine can achieve when adequate resources and collaborative frameworks are in place (Graham, 2020). Scientists applied decades of prior research on mRNA technology and coronavirus biology to create safe and effective vaccines in less than a year.

Yet the pandemic also highlighted translational development challenges. Seniors and people with disabilities faced particular difficulties accessing vaccines despite being at highest risk for severe illness. Physical barriers at vaccination sites, limited transportation options, concerns about adverse effects in people with pre-existing conditions, and insufficient outreach to long-term care facilities all impeded equitable vaccine distribution (Landes et al., 2021). Addressing these issues required intentional translational development efforts, including mobile vaccination clinics, enhanced communication strategies, and specialized protocols for immunocompromised individuals.

Regenerative Medicine: Promise and Challenges

The field of regenerative medicine offers tremendous promise for both seniors and people with disabilities through translational approaches. Stem cell therapies, tissue engineering, and gene therapy have the potential to restore function that was previously thought permanently lost. Research in these areas has progressed from basic laboratory science to early clinical applications, with some treatments now available for conditions like certain types of blindness and blood disorders (Trounson & DeWitt, 2016).

However, translational challenges abound. The science behind many regenerative therapies is complex and not yet fully understood. Manufacturing these biological treatments at scale while maintaining quality and safety is technically difficult. The costs are often astronomical, raising questions about who will be able to access these potentially life-changing therapies. Regulatory frameworks struggle to keep pace with scientific innovation, creating uncertainty about approval pathways.

For seniors specifically, regenerative medicine raises intriguing questions about the goals of treatment. Is the aim to extend lifespan, improve quality of life during later years, or both? How do we balance the potential benefits of aggressive interventions against the risks in a population that may be more vulnerable to side effects? These questions require input from older adults themselves, their caregivers, ethicists, and healthcare providers - exemplifying the multidisciplinary approach central to translational development (Faden et al., 2003).

Implementation Science: Making Evidence Work in Practice

The concept of "implementation science" has emerged as a crucial component of translational development. This field specifically studies the methods and strategies needed to integrate evidence-based interventions into routine healthcare practice. It recognizes that even when we know what works, getting healthcare systems and providers to consistently implement effective practices remains a major challenge (Eccles & Mittman, 2006).

For people with disabilities, implementation science addresses questions like how to ensure that primary care physicians receive adequate training in disability-related health issues, how to make medical equipment accessible to people with different types of impairments, and how to create clinical workflows that accommodate patients who may need additional time or communication support. These may seem like practical details rather than groundbreaking science, but they are essential to ensuring that medical advances actually reach the people who need them.

Pain Management: A Translational Case Study

Pain management in older adults provides a compelling case study in the importance of translational approaches. Chronic pain affects a substantial portion of seniors, yet pain has historically been undertreated in this population due to concerns about side effects from pain medications, beliefs that pain is a normal part of aging, and communication barriers when cognitive impairment is present (Kaye et al., 2010).

Translational medicine has contributed new pain management options, including medications with better safety profiles for older adults, targeted nerve stimulation techniques, and improved understanding of pain mechanisms in aging bodies. Translational development research has focused on implementing comprehensive pain assessment protocols in nursing homes and other care settings, training providers to recognize and treat pain in patients with dementia, and developing non-pharmacological interventions like physical therapy and mindfulness-based approaches that may be particularly appropriate for older adults.

Health Informatics and Big Data Analytics

The role of health informatics and big data analytics represents an increasingly important frontier in translational medicine and development. Electronic health records, wearable sensors, genetic databases, and other digital tools generate enormous amounts of health data. When analyzed appropriately, this information can reveal patterns that lead to new treatments or identify groups of patients who respond particularly well to specific interventions (Abernethy et al., 2010).

For seniors and people with disabilities, these technologies offer both opportunities and risks. On one hand, data analytics might identify previously unrecognized treatment options for rare conditions or reveal that a medication approved for one condition is effective for another. Remote monitoring technologies can help older adults remain in their homes longer while still receiving attentive medical care. On the other hand, privacy concerns, digital divides that exclude those without technological access, and the potential for algorithms to perpetuate existing healthcare disparities all demand careful attention from a translational development perspective (Vayena et al., 2018).

Precision Medicine: Tailoring Treatment to the Individual

Precision, or personalized, medicine, which tailors treatment to individual patient characteristics including genetics, lifestyle, and environment, represents a natural evolution of translational approaches. Rather than assuming all patients will respond identically to a treatment, precision medicine recognizes that individual variation matters. Pharmacogenomics, for instance, can identify genetic variations that affect how a person metabolizes certain medications, allowing doctors to choose drugs and dosages that will be most effective and least likely to cause side effects for that specific patient (Hamburg & Collins, 2010).

This approach holds particular relevance for seniors, who often take multiple medications and face increased risks of drug interactions and adverse effects. A precision medicine approach might use genetic testing to predict which antidepressant will work best for an older adult, which pain medication they can safely take given their other prescriptions, or which cancer treatment is most likely to be effective based on the specific genetic mutations in their tumor.

Supporting the Caregivers

The challenge of caregiver support illustrates how translational development must extend beyond the patient to encompass the broader care ecosystem. Many seniors and people with disabilities rely on family caregivers who often receive little training or support. Translational research has begun addressing this gap by developing and testing interventions to reduce caregiver stress, improve caregiving skills, and prevent caregiver burnout (Gitlin et al., 2010).

These interventions might include training programs that teach caregivers how to safely assist with transfers and mobility, support groups that provide emotional support and practical advice, respite care services that give caregivers necessary breaks, and technologies that make caregiving tasks easier. The translational development challenge involves figuring out how to make these evidence-based interventions available to the millions of family caregivers who need them, many of whom face time constraints, financial limitations, and difficulty accessing services.

Rehabilitation Science: Restoring Function and Independence

Rehabilitation science exemplifies the integration of translational medicine and development principles. Modern rehabilitation combines insights from neuroscience, engineering, psychology, and other fields to develop interventions that help people regain function after injury or illness or adapt to permanent impairments. Robotic therapy for stroke recovery, virtual reality for pain management and physical therapy, and advanced prosthetics that respond to neural signals all emerged from translational research programs (Deutsch et al., 2011).

The translational development aspect of rehabilitation involves making these innovations accessible and practical. A sophisticated robotic rehabilitation system might be effective in research settings, but if it requires a PhD to operate, costs hundreds of thousands of dollars, and needs a dedicated room, its real-world impact will be limited. Translational development efforts focus on creating simplified versions suitable for clinical use, training therapists to use new technologies effectively, and developing payment models that make innovative therapies financially viable.

Addressing Health Disparities

Health disparities research has revealed that seniors and people with disabilities from racial and ethnic minority communities often face compounded disadvantages in accessing medical advances. These populations experience higher rates of certain diseases, lower rates of treatment, and worse health outcomes across numerous conditions (Minkler et al., 2012). Translational medicine and development must intentionally address these disparities rather than assuming that innovations will automatically benefit all groups equally.

This might involve recruiting diverse participants in clinical trials to ensure treatments are tested in the populations most affected by a condition, developing culturally appropriate education materials, training healthcare providers about implicit bias, and addressing structural barriers like transportation and language access. Some researchers now use community-based participatory research methods, where community members are active partners in all stages of research, from identifying priorities to interpreting findings and implementing solutions.

The Economics of Innovation and Access

The economics of translational medicine and development cannot be ignored, particularly when considering seniors and people with disabilities who often live on fixed incomes. Breakthrough treatments may cost hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars, raising profound questions about healthcare justice and resource allocation. Who decides which innovations are worth the investment? How do we balance the development of treatments for rare conditions against common diseases affecting millions? What obligations do pharmaceutical companies have to make their products affordable? (Cohen et al., 2007).

Value-based healthcare models attempt to address these questions by evaluating treatments based on the outcomes they achieve relative to their costs. For seniors, this might mean prioritizing interventions that maintain independence and quality of life, even if they don't extend lifespan. For people with disabilities, it requires recognizing that quality of life should be defined by the individuals themselves rather than by external observers who might undervalue life with a disability.

Digital Therapeutics: Software as Medicine

Digital therapeutics represent an emerging area where translational medicine meets modern technology. These are software-based interventions that can prevent, manage, or treat medical conditions. Smartphone apps that deliver cognitive behavioral therapy for depression, virtual reality programs for pain management, and digital platforms that help people manage chronic conditions like diabetes all fall into this category (Patel et al., 2020).

For seniors and people with disabilities, digital therapeutics offer potential advantages including convenience, lower cost compared to traditional interventions, and the ability to receive treatment at home. However, digital literacy, access to necessary technology, and the need for human interaction in some cases present challenges that translational development must address. Not every senior is comfortable using a smartphone app, and people with certain disabilities may need specialized interfaces or alternative formats.

Aging in Place: Supporting Independence at Home

The concept of "aging in place" - enabling older adults to remain in their own homes and communities as they age - has become a priority in public health and social policy. Translational research supports this goal by developing technologies and interventions that make aging in place safer and more feasible. Fall detection systems, medication management tools, home modifications that improve accessibility, and telehealth services that reduce the need for medical travel all contribute to this objective (Wiles et al., 2012).

Translational development research examines how to implement these solutions effectively. This includes understanding what motivates or prevents older adults from adopting new technologies, how to fund home modifications for those with limited resources, how to integrate informal caregiving with formal healthcare services, and how to create community programs that reduce social isolation. The research must account for the tremendous diversity among older adults - someone who is 65 and healthy has very different needs from someone who is 85 with multiple chronic conditions.

Mental Health: An Often-Overlooked Priority

Mental health represents a critical yet often overlooked area where translational approaches could benefit seniors and people with disabilities. Depression, anxiety, and other mental health conditions are common in these populations yet frequently go unrecognized and untreated. Translational medicine has contributed new understanding of the biological basis of mental health conditions and new treatment options including medications with fewer side effects and brain stimulation techniques (Insel, 2009).

Translational development addresses the barriers that prevent people from accessing mental health care. Stigma remains a significant issue, particularly among older adults who may have grown up in an era when mental health problems were rarely discussed. People with physical disabilities may find mental health services physically inaccessible or may encounter providers who lack understanding of how disability and mental health intersect. Solutions require not just better treatments but better systems for delivering those treatments in ways that are accessible, affordable, and culturally appropriate.

Artificial Intelligence: The Next Frontier

The future of translational medicine and development increasingly involves artificial intelligence and machine learning. These technologies can analyze complex datasets to identify patterns humans might miss, predict which patients are at risk for certain conditions, and even suggest personalized treatment plans. AI systems are being developed to read medical images, predict medication responses, and monitor patients for early signs of deterioration (Topol, 2019).

For seniors and people with disabilities, AI offers both promise and peril. Predictive algorithms might identify older adults at risk of falls, allowing preventive interventions, or flag concerning changes in someone's condition before they become emergencies. However, if the data used to train AI systems doesn't adequately represent these populations, the algorithms may perform poorly or even perpetuate biases. Ensuring that AI development follows translational principles - including diverse representation in training data and involvement of end users in design - will be crucial.

Navigating the Regulatory Landscape

The regulatory environment for medical innovations continues to evolve in response to the rapid pace of translational research. The FDA and other regulatory agencies face the challenge of ensuring safety and efficacy while not unnecessarily delaying access to potentially life-saving treatments. Accelerated approval pathways, breakthrough therapy designations, and adaptive trial designs all represent attempts to speed the translational process while maintaining appropriate safeguards (Sherman et al., 2013).

These regulatory considerations have particular implications for seniors and people with disabilities. Expedited approvals for serious conditions may allow access to promising treatments years earlier than traditional pathways would permit. However, this comes with increased uncertainty about long-term effects, and these populations may be particularly vulnerable to unexpected adverse effects. Patient advocacy groups play an important role in regulatory discussions, representing the voices of those who will ultimately use approved treatments.

Global Health Perspectives

Global health perspectives on translational medicine and development highlight that innovations must be appropriate for diverse settings with varying resources. A treatment that requires expensive equipment and highly specialized personnel may have limited applicability in low-resource settings, whether in developing countries or underserved areas of wealthy nations. Frugal innovation and reverse innovation - developing simple, affordable solutions that can be used anywhere - represent important translational development strategies (Bhatti et al., 2018).

This global perspective matters for seniors and people with disabilities in all settings. Solutions developed for resource-limited environments often emphasize simplicity, affordability, and ease of use - characteristics that can benefit anyone. A low-cost prosthetic leg designed for use in settings without advanced medical facilities might also serve someone in a wealthy country who cannot afford expensive alternatives. A telemedicine platform developed to reach rural populations in developing nations might help isolated seniors anywhere.

Training the Next Generation of Healthcare Providers

Education and training of healthcare providers represent critical components of translational development that are sometimes overlooked. Medical, nursing, and allied health professional education must evolve to keep pace with new knowledge and innovations. This includes not just teaching about new treatments but also fostering attitudes and skills that support patient-centered care, cultural competency, and effective communication with diverse populations (Lucey, 2013).

For care of seniors and people with disabilities, this educational imperative is particularly acute. Geriatrics and disability medicine receive limited attention in many training programs, despite the fact that healthcare providers will spend much of their careers caring for these populations. Translational efforts must therefore include developing and implementing curricula that prepare providers to deliver high-quality, evidence-based care to older adults and people with disabilities.

Patient Engagement and Empowerment

Patient engagement and empowerment have emerged as central themes in modern translational approaches. Rather than positioning patients as passive recipients of medical interventions, contemporary models emphasize their role as active participants in their own care and as partners in research. Patient-reported outcomes, shared decision-making, and patient advisory boards all reflect this shift (Carman et al., 2013).

This participatory approach resonates particularly strongly with disability rights principles and with older adults who often have substantial experience managing chronic conditions. When seniors and people with disabilities have genuine voice in translational research, the resulting innovations are more likely to address priorities that matter to them. This might mean focusing more on quality of life and function rather than just extending survival, or developing solutions that enhance autonomy and dignity rather than just managing symptoms.

Translational Approaches to Public Health

The intersection of translational medicine and public health offers opportunities to move beyond individual patient care to population-level impact. Prevention strategies informed by translational research can reduce the burden of disease before it occurs. Vaccination programs, fall prevention initiatives, diabetes prevention programs, and other public health interventions all benefit from translational approaches that move evidence into practice (Khoury et al., 2012).

For seniors, prevention remains crucial even at advanced ages. Programs that promote physical activity, social engagement, and cognitive stimulation can help maintain function and independence. For people with disabilities, prevention includes both preventing secondary conditions related to primary disabilities and ensuring access to routine preventive care like cancer screenings that are sometimes overlooked in this population.

References:

Abernethy, A. P., Etheredge, L. M., Ganz, P. A., Wallace, P., German, R. R., Neti, C., ... & Tunis, S. R. (2010). Rapid-learning system for cancer care. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 28(27), 4268-4274.

Balas, E. A., & Boren, S. A. (2000). Managing clinical knowledge for health care improvement. Yearbook of Medical Informatics, 9(01), 65-70.

Bhatti, Y., Ventresca, M., Thadaney, G., & Prime, M. (2018). Towards a framework for frugal innovation: Key concepts and priorities. SSRN Electronic Journal.

Blabe, C. H., Gilja, V., Chestek, C. A., Shenoy, K. V., Anderson, K. D., & Henderson, J. M. (2015). Assessment of brain-machine interfaces from the perspective of people with paralysis. Journal of Neural Engineering, 12(4), 043002.

Carman, K. L., Dardess, P., Maurer, M., Sofaer, S., Adams, K., Bechtel, C., & Sweeney, J. (2013). Patient and family engagement: A framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Affairs, 32(2), 223-231.

Charlton, J. I. (1998). Nothing About Us Without Us: Disability Oppression and Empowerment. University of California Press.

Cohen, J. P., Stolk, E., & Niezen, M. (2007). The increasingly complex fourth hurdle for pharmaceuticals. Pharmacoeconomics, 25(9), 727-734.

Cohen, S. Y., Mimoun, G., Oubraham, H., Zourdani, A., Malbrel, C., Queré, S., & Schneider, V. (2010). Changes in visual acuity in patients with wet age-related macular degeneration treated with intravitreal ranibizumab in daily clinical practice. Eye, 24(5), 872-876.

Deutsch, J. E., Lewis, J. A., & Burdea, G. (2011). Technical and patient performance using a virtual reality-integrated telerehabilitation system: Preliminary finding. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, 15(1), 30-35.

Eccles, M. P., & Mittman, B. S. (2006). Welcome to implementation science. Implementation Science, 1(1), 1-3.

Faden, R. R., Dawson, L., Bateman-House, A. S., Agnew, D. M., Bok, H., Brock, D. W., ... & Tunis, S. (2003). Public stem cell banks: Considerations of justice in stem cell research and therapy. Hastings Center Report, 33(6), 13-27.

Gitlin, L. N., Belle, S. H., Burgio, L. D., Czaja, S. J., Mahoney, D., Gallagher-Thompson, D., ... & Ory, M. G. (2010). Effect of multicomponent interventions on caregiver burden and depression. Psychology and Aging, 18(3), 361-374.

Graham, B. S. (2020). Rapid COVID-19 vaccine development. Science, 368(6494), 945-946.

Hamburg, M. A., & Collins, F. S. (2010). The path to personalized medicine. New England Journal of Medicine, 363(4), 301-304.

Hurria, A., Levit, L. A., Dale, W., Mohile, S. G., Muss, H. B., Fehrenbacher, L., ... & Cohen, H. J. (2016). Improving the evidence base for treating older adults with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology statement. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 33(32), 3826-3833.

Iezzoni, L. I., & O'Day, B. L. (2006). More Than Ramps: A Guide to Improving Health Care Quality and Access for People with Disabilities. Oxford University Press.

Insel, T. R. (2009). Translating scientific opportunity into public health impact. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66(2), 128-133.

Kaye, A. D., Baluch, A., & Scott, J. T. (2010). Pain management in the elderly population: A review. Ochsner Journal, 10(3), 179-187.

Khoury, M. J., Gwinn, M., Yoon, P. W., Dowling, N., Moore, C. A., & Bradley, L. (2007). The continuum of translation research in genomic medicine. Genetics in Medicine, 9(10), 665-674.

Khoury, M. J., Gwinn, M., & Ioannidis, J. P. (2012). The emergence of translational epidemiology: From scientific discovery to population health impact. American Journal of Epidemiology, 172(5), 517-524.

Landes, S. D., Turk, M. A., Formica, M. K., McDonald, K. E., & Stevens, J. D. (2021). COVID-19 outcomes among people with intellectual and developmental disability living in residential group homes in New York State. Disability and Health Journal, 14(1), 100969.

Lucey, C. R. (2013). Medical education: Part of the problem and part of the solution. JAMA Internal Medicine, 173(17), 1639-1643.

Mangoni, A. A., & Jackson, S. H. (2004). Age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: Basic principles and practical applications. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 57(1), 6-14.

Minkler, M., Fuller-Thomson, E., & Guralnik, J. M. (2012). Gradient of disability across the socioeconomic spectrum in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine, 355(7), 695-703.

Patel, N. A., Butte, A. J., et al. (2020). Digital therapeutics in chronic disease management. NPJ Digital Medicine, 3(1), 1-3.

Peek, S. T., Wouters, E. J., van Hoof, J., Luijkx, K. G., Boeije, H. R., & Vrijhoef, H. J. (2014). Factors influencing acceptance of technology for aging in place. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 83(4), 235-248.

Rubio, D. M., Schoenbaum, E. E., Lee, L. S., Schteingart, D. E., Marantz, P. R., Anderson, K. E., ... & Esposito, K. (2010). Defining translational research: Implications for training. Academic Medicine, 85(3), 470-475.

Sherman, R. E., Li, J., Shapley, S., Robb, M., & Woodcock, J. (2013). Expediting drug development - The FDA's new breakthrough therapy designation. New England Journal of Medicine, 369(20), 1877-1880.

Topol, E. J. (2019). High-performance medicine: The convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nature Medicine, 25(1), 44-56.

Trounson, A., & DeWitt, N. D. (2016). Pluripotent stem cells progressing to the clinic. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 17(3), 194-200.

Vayena, E., Blasimme, A., & Cohen, I. G. (2018). Machine learning in medicine: Addressing ethical challenges. PLoS Medicine, 15(11), e1002689.

Weise, M., Almassi, N. E., & Doyal, L. (2020). The inclusion of people with disabilities in medical research. Journal of Medical Ethics, 46(2), 130-133.

Wiles, J. L., Leibing, A., Guberman, N., Reeve, J., & Allen, R. E. (2012). The meaning of "aging in place" to older people. Gerontologist, 52(3), 357-366.

Witham, M. D., & George, J. (2014). Age-friendly clinical trials. Age and Ageing, 43(3), 297-298.

Woolf, S. H. (2008). The meaning of translational research and why it matters. JAMA, 299(2), 211-213.

Insights, Analysis, and Developments

Editorial Note: The promise of translational medicine and translational development extends far beyond the laboratory bench or the pages of medical journals. For seniors navigating the complexities of aging and for people with disabilities seeking greater independence and quality of life, these fields offer tangible hope grounded in rigorous science and practical wisdom. Yet realizing this promise requires more than brilliant researchers or innovative technologies - it demands a fundamental commitment to inclusion, equity, and partnership with the communities we aim to serve. As we move forward, the most successful translational efforts will be those that genuinely listen to the voices of older adults and people with disabilities, not as subjects to be studied but as essential collaborators whose lived experience guides us toward innovations that truly matter. The future of translational science is not just about moving faster from discovery to deployment; it's about ensuring that when we arrive, we've brought everyone along - Disabled World (DW). Author Credentials: Ian is the founder and Editor-in-Chief of Disabled World, a leading resource for news and information on disability issues. With a global perspective shaped by years of travel and lived experience, Ian is a committed proponent of the Social Model of Disability-a transformative framework developed by disabled activists in the 1970s that emphasizes dismantling societal barriers rather than focusing solely on individual impairments. His work reflects a deep commitment to disability rights, accessibility, and social inclusion. To learn more about Ian's background, expertise, and accomplishments, visit his full biography.

Author Credentials: Ian is the founder and Editor-in-Chief of Disabled World, a leading resource for news and information on disability issues. With a global perspective shaped by years of travel and lived experience, Ian is a committed proponent of the Social Model of Disability-a transformative framework developed by disabled activists in the 1970s that emphasizes dismantling societal barriers rather than focusing solely on individual impairments. His work reflects a deep commitment to disability rights, accessibility, and social inclusion. To learn more about Ian's background, expertise, and accomplishments, visit his full biography.