Quasi-Life: Understanding Biology's In-Between Entities

Author: Ian C. Langtree - Writer/Editor for Disabled World (DW)

Published: 2025/12/14 - Updated: 2025/12/15

Publication Type: Scholarly Paper

Category Topic: Journals - Papers - Related Publications

Page Content: Synopsis - Introduction - Main - Insights, Updates

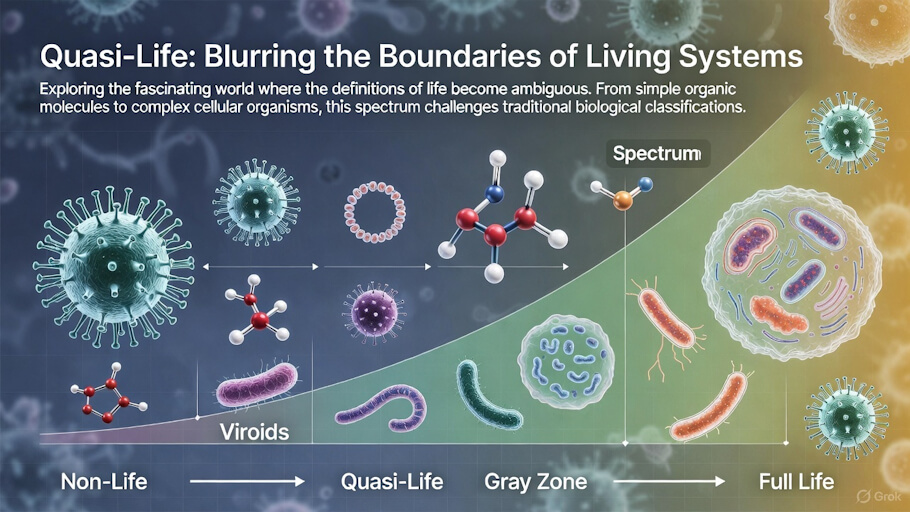

Synopsis: The boundary between life and non-life has long fascinated scientists, philosophers, and medical researchers alike. In this exploration of quasi-life - those enigmatic entities that occupy the gray zone between the living and the inanimate - we examine not only their remarkable biological properties but also their profound implications for human health. As our global population ages and more individuals live with disabilities, understanding these microscopic entities becomes increasingly critical. Viruses, viroids, and prions, the primary examples of quasi-life, disproportionately affect older adults and immunocompromised individuals, making this knowledge essential for developing better protective strategies and treatments. This paper explores what quasi-life means, how these entities function, and why they matter particularly for our most vulnerable populations - Disabled World (DW).

- Definition: Quasi-Life

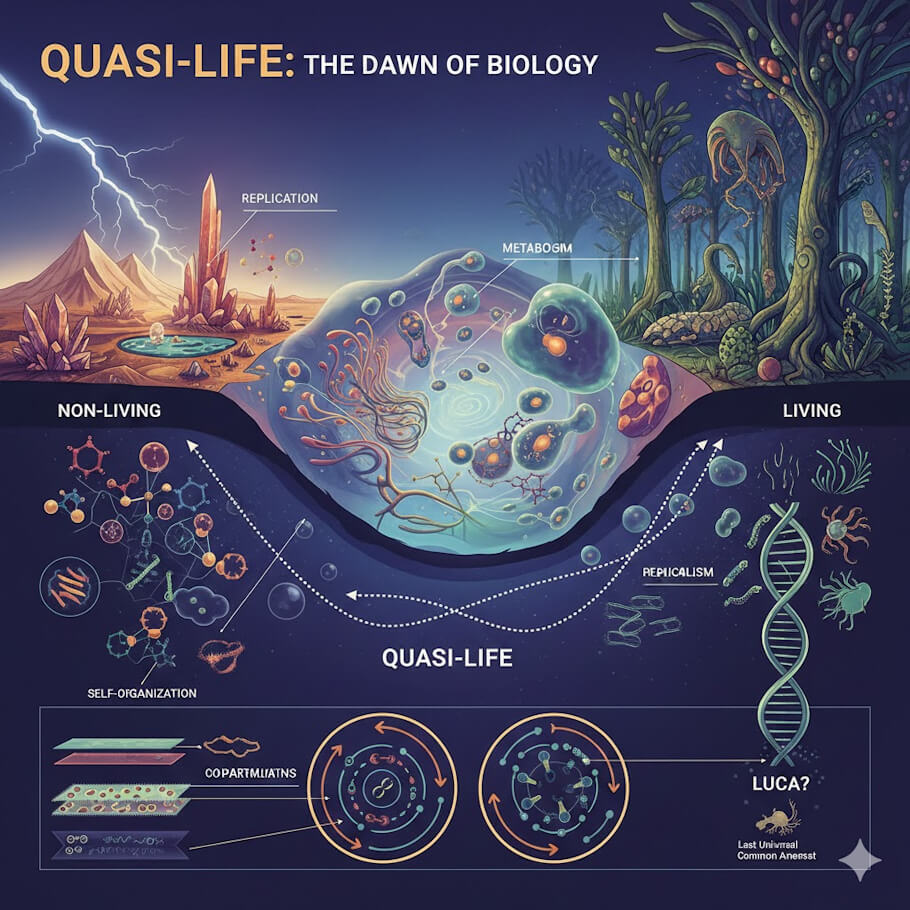

Quasi-life refers to biological entities that exist in the nebulous space between living organisms and inert matter - structures that possess genetic material or proteins capable of replication, yet lack the ability to reproduce independently. Unlike bacteria or other microorganisms that can grow and divide on their own, quasi-life forms such as viruses, viroids, and prions must hijack the cellular machinery of living hosts to propagate. They don't metabolize nutrients, they can't respond to environmental stimuli in the way living cells do, and they're technically classified as non-living. Yet these entities can evolve, adapt to new hosts, and cause devastating diseases that have shaped human history. What makes them particularly fascinating - and medically significant - is this paradox: they're chemically inert particles when isolated, essentially dormant specks of protein and nucleic acid, but once they encounter a suitable host cell, they spring into action with remarkable efficiency. This duality challenges our fundamental definitions of what constitutes life and forces us to recognize that biology doesn't always fit into neat categories. The line between animate and inanimate turns out to be far blurrier than we once imagined.

Introduction

Understanding Quasi-Life: Biological Entities at the Edge of Living and Their Impact on Vulnerable Populations

This paper examines how quasi-life entities (viruses, viroids, prions) exist at the boundary between living and non-living, explains their biological properties, and discusses their particular relevance to vulnerable populations including older adults and people with disabilities.

The natural world presents us with entities that challenge our fundamental understanding of what it means to be alive. While most organisms clearly fall into the category of "living" - capable of independent reproduction, metabolism, and response to environmental stimuli - there exists a fascinating category of biological entities that blur this distinction. These entities, collectively termed "quasi-life," possess some characteristics of living organisms while lacking others, creating a conceptual puzzle that has occupied scientists for decades (Prusiner, 1998).

The term "quasi-life" comes from the Latin prefix meaning "resembling" or "apparently but not actually." In biological contexts, quasi-life refers to structures containing genetic material (RNA or DNA) or proteins that exhibit life-like properties, particularly the ability to replicate, but cannot do so independently. These entities must hijack the cellular machinery of truly living organisms to reproduce, placing them in a unique biological category distinct from both living cells and inert matter.

Understanding quasi-life is not merely an academic exercise in biological classification. These entities include some of the most significant disease-causing agents known to medicine, from the influenza viruses that cause seasonal epidemics to the prions responsible for invariably fatal neurodegenerative diseases. The practical importance of this knowledge becomes especially acute when we consider vulnerable populations, including older adults and individuals with disabilities, who face heightened risks from infections caused by these quasi-life forms.

Main Content

Defining Quasi-Life: The Characteristics That Set These Entities Apart

Quasi-life entities share several defining characteristics that distinguish them from both fully living organisms and completely non-living matter. All forms of life as we know them are based on ribonucleic acid (RNA), that remarkable molecule capable of both replicating genetic material and acting as a catalyst for cellular chemical processes (Science for the Public, n.d.). Quasi-life forms contain fragments of this RNA, or the related molecule DNA, but these fragments are incomplete compared to living cells.

The crucial defining feature of quasi-life is obligate cellular parasitism - these entities absolutely require the machinery of living cells to reproduce. A virus particle sitting on a doorknob or countertop is essentially inert, causing no harm and carrying out no biological processes. Only when it encounters and invades a suitable host cell does it spring into action, co-opting that cell's protein-making machinery to produce copies of itself. Because they cannot survive or reproduce independently, quasi-life forms are technically classified as non-living structures despite their ability to evolve, adapt, and cause disease.

Unlike living organisms, quasi-life entities do not carry out metabolism - they don't transform energy or engage in the chemical processes that sustain life. They don't grow in the traditional sense, and they can only be seen with powerful electron microscopes. Yet they can cause devastating diseases, evolve to evade immune responses and medical treatments, and fundamentally alter the DNA of organisms they infect, even changing the course of evolutionary history.

The Major Categories of Quasi-Life

Viruses: The Most Familiar Quasi-Life Forms

Viruses represent the most familiar and medically significant category of quasi-life. These entities consist of genetic material - either DNA or RNA, but never both - surrounded by a minimal protein coat called a capsid. This simple structure belies their enormous impact on human health and history. Viruses have caused some of humanity's most devastating pandemics, from the 1918 Spanish flu that killed tens of millions to the recent COVID-19 pandemic that fundamentally altered global society.

The average virus contains approximately ten genes and a minimal protein shell, making it remarkably simple compared to even the simplest bacteria. However, some recently discovered "giant viruses" challenge our understanding of the virus-life boundary. Mimivirus and CroV, which infect single-celled organisms like amoebas, possess hundreds of genes and large, complex protein shells. More surprisingly, they can produce proteins - a capability traditionally thought impossible for viruses and typically reserved for living cells (Science for the Public, n.d.). These discoveries suggest that the distinction between quasi-life and true life may be less clear-cut than previously believed, potentially requiring new intermediate categories.

Viruses replicate by invading host cells and taking over their translation mechanisms - the cellular machinery that normally produces proteins needed by the cell itself. Once inside, the virus essentially reprograms the cell to become a virus factory, churning out new viral particles that can then infect additional cells. This process often damages or destroys the host cell, producing the symptoms we associate with viral infections.

The diversity of viruses is staggering. They infect nearly all forms of life, from bacteria and archaea to plants, animals, and fungi. Some viruses have positive-sense RNA genomes that can be directly translated by host cell ribosomes, while others have negative-sense RNA that must first be transcribed. DNA viruses may integrate their genetic material directly into the host's genome, sometimes remaining dormant for years before reactivating. This remarkable adaptability and diversity make viruses formidable opponents in medicine and public health.

Viroids: The Minimalist Replicators

Viroids represent an even more stripped-down form of quasi-life than viruses. Discovered in 1971 by pathologist Theodor Diener, viroids consist only of short strands of circular RNA - they lack even the protein coat that protects viral genetic material. Despite this extreme simplicity, viroids can cause devastating diseases, particularly in plants (Diener, 1971).

The first viroid discovered caused potato spindle tuber disease, which produces slower sprouting and various deformities in potato plants. Since then, numerous other viroids have been identified, affecting commercially important crops including tomatoes, cucumbers, chrysanthemums, avocados, and coconut palms. The Tomato planta macho viroid causes loss of chlorophyll, disfigured and brittle leaves, and very small tomatoes, resulting in significant agricultural losses.

Viroids are much smaller than viruses, containing only a shred of genetic information. Yet they share with viruses the ability to replicate by commandeering host cell machinery. The RNA in viroids coils around itself to become double-stranded, providing some structural stability. While viroids don't directly affect humans, they can cause crop failures resulting in substantial economic impact and food security concerns.

One viroid does affect humans: the hepatitis D viroid, which can only enter liver cells when enclosed in a capsid borrowed from the hepatitis B virus. This unusual arrangement makes hepatitis D a dependent pathogen that requires co-infection with hepatitis B to cause disease.

Prions: The Protein-Only Infectious Agents

Prions represent perhaps the most unusual and counterintuitive form of quasi-life. The term "prion," coined by Nobel laureate Stanley Prusiner in 1982, stands for "proteinaceous infectious particle." Unlike viruses and viroids, prions contain no nucleic acids whatsoever - no DNA or RNA. They consist entirely of misfolded proteins, yet they can cause infectious disease and replicate their misfolded state in other proteins.

This concept initially met with fierce resistance from the scientific community. For decades, the central dogma of biology held that all infectious agents must contain genetic material to replicate and cause disease. The idea of an infectious protein without any DNA or RNA seemed to violate fundamental biological principles. However, Prusiner's meticulous research eventually convinced most scientists that prions do indeed exist, earning him the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1997.

Prions cause a group of invariably fatal neurodegenerative diseases called transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs). In humans, these include Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD), kuru, Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker syndrome, and fatal familial insomnia. In animals, prion diseases include scrapie in sheep, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE or "mad cow disease") in cattle, and chronic wasting disease in deer and elk.

The mechanism by which prions cause disease is remarkably sinister. The normal prion protein, designated PrP^c^, pronounced "Pee-Are-Pee-Cee" (P-R-P-C), exists naturally in the body, particularly in brain tissue, though its exact function remains somewhat mysterious. When the abnormal form, PrP^sc^, pronounced "Pee-Are-Pee-Scrapie", enters the body - through contaminated food, medical instruments, or inherited genetic mutations - it acts as a template that converts normal PrP^c^ into the misfolded PrP^sc^ form. This creates a chain reaction, with each newly misfolded protein converting more normal proteins, leading to exponential accumulation of the abnormal form.

The misfolded prion proteins aggregate into clumps called amyloids, which accumulate in brain tissue. This accumulation causes progressive neurodegeneration, creating the characteristic "sponge-like" appearance of affected brains riddled with holes. Symptoms typically include rapidly progressive dementia, loss of motor control, unusual behaviors, and personality changes. The diseases progress relentlessly and are always fatal, usually within months to a few years of symptom onset.

What makes prions particularly challenging is their extreme resistance to standard sterilization methods. They resist chemical disinfection, heat, radiation, and other treatments that would easily destroy bacteria or viruses. This resilience complicates medical equipment sterilization and raises serious concerns about iatrogenic transmission - disease spread through medical procedures. Prions can be transmitted through contaminated surgical instruments, tissue grafts, and cadaveric-derived hormones.

Recent research has revealed even more concerning implications of prion-like mechanisms. Proteins similar to prions may play roles in other neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and Huntington's disease. While these conditions aren't infectious in the traditional sense, they involve similar processes of protein misfolding and aggregation spreading through neural tissue (Wikipedia, 2024). This discovery has opened new avenues for understanding and potentially treating these common age-related neurological disorders.

Study Reveals Characteristics of LUCA, the Last Universal Common Ancestor: The nature of the Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA) and its impact on the early Earth system.

Quasi-Life and Vulnerable Populations: The Intersection with Aging and Disability

The significance of understanding quasi-life extends far beyond academic interest in biological classification. These entities pose particular risks to vulnerable populations, especially older adults and individuals with disabilities. This heightened vulnerability stems from multiple interconnected factors related to immune function, physiological changes with aging, and the nature of disability itself.

Aging and Increased Susceptibility to Viral Infections

As people age, their immune systems undergo a process called immunosenescence - a gradual deterioration of immune function that makes older adults more susceptible to infections and less responsive to vaccinations. This age-related decline in immunity means that viral infections, which are forms of quasi-life, pose significantly greater risks to elderly populations.

The vulnerability of older adults to influenza viruses exemplifies this relationship. Seasonal flu causes high morbidity and mortality particularly in people over 65, those with chronic health conditions affecting the heart and lungs, and immunocompromised individuals. The recent COVID-19 pandemic starkly illustrated how viral infections disproportionately affect elderly populations. Multiple studies documented that older adults experienced higher rates of severe disease, hospitalization, and death from SARS-CoV-2 infection compared to younger individuals (CDC, 2024).

The mechanisms behind this increased vulnerability are multifaceted. The blood-brain barrier becomes more permeable with age, potentially allowing viruses easier access to the central nervous system. Cellular immune responses weaken, reducing the body's ability to detect and eliminate infected cells. Age-related increases in oxidative stress and impaired energy production render neurons more vulnerable to viral toxicity. Additionally, inflammatory processes become dysregulated with aging, leading to chronic low-grade inflammation that can actually worsen outcomes during acute infections.

Research on influenza demonstrates the protective role of normal prion proteins in fighting viral infections. Studies have shown that mice lacking the cellular prion protein (PrP^c^) were highly susceptible to influenza A viruses, with higher mortality rates than normal mice. The affected lungs showed severe injury, increased inflammation, and elevated levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS). This suggests that normal prion protein may serve a protective function against viral infections, and age-related changes in protein expression could contribute to increased vulnerability (Nakamura et al., 2018).

Prion Diseases and the Elderly

Prion diseases predominantly affect older adults, with most cases of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease striking people around age 60. This age association likely reflects both the long incubation periods of prion diseases (which can span decades) and age-related changes in protein homeostasis - the cellular mechanisms that maintain proper protein folding and remove misfolded proteins.

During normal aging, the efficiency of protein quality control systems declines. Cellular chaperone proteins that help maintain proper protein folding become less effective, and systems for clearing damaged proteins work less efficiently. This age-related decline in proteostasis (protein homeostasis) may explain why prion diseases and other protein misfolding disorders predominantly affect older individuals.

The connection between prions and aging extends beyond classical prion diseases. Recent research suggests that prion-like mechanisms - proteins that misfold and induce misfolding in neighboring proteins - may contribute to common age-related neurodegenerative diseases. Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and ALS all involve accumulation of misfolded proteins that spread through brain tissue in patterns reminiscent of prion diseases. While these conditions aren't infectious like true prion diseases, understanding their prion-like properties opens new therapeutic possibilities.

Multiple epidemiological studies have revealed troubling connections between SARS-CoV-2 infection (COVID-19) and subsequent neurological problems, including onset of neurodegenerative diseases. The SARS-CoV-2 spike protein contains prion-like domains that may promote protein aggregation. Elderly COVID-19 patients and those with pre-existing neurological conditions showed particular vulnerability to these neurological complications, suggesting complex interactions between viral infection, aging, prion-like mechanisms, and neurodegeneration (Lukiw et al., 2022).

Implications for Individuals with Disabilities

People with disabilities face increased vulnerability to quasi-life entities through several mechanisms. Many disabilities, particularly those affecting neurological function or involving immunodeficiency, directly impair the body's ability to fight infections. Individuals with mobility impairments may have increased exposure to healthcare settings where infectious disease transmission risks are higher. Those with intellectual or developmental disabilities may have difficulty implementing protective behaviors like proper hand hygiene or mask-wearing during outbreaks.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, people with disabilities experienced dramatically worse outcomes. They faced barriers to accessing testing and treatment, had higher rates of severe disease, and experienced hundreds of thousands of deaths. One study found that 82% of physicians believed people with significant disabilities have worse quality of life, and only 57% welcomed disabled patients into their practices (Campbell et al., 2021). This bias in the healthcare system compounds the biological vulnerabilities that make infectious diseases more dangerous for people with disabilities.

The intersection of disability and aging creates particular vulnerability. About one-third of people aged 65 and older - nearly 19 million seniors in the United States - have a disability. These individuals face overlapping challenges: age-related immune decline, functional limitations from their disabilities, potential biases from healthcare providers, and often multiple chronic health conditions that further compromise their resilience.

Central nervous system (CNS) infections from viruses and prions present especially high rates of morbidity and mortality in both children and the elderly. The CNS becomes particularly vulnerable to infectious agents during aging because immune surveillance decreases, some infectious agents can transfer directly from peripheral nerves into the CNS, and age-related metabolic changes render neurons more susceptible to damage from viral or prion proteins (Mattson & Magnus, 2006).

Healthcare System Preparedness and Accessibility

The healthcare system's readiness to serve vulnerable populations affected by quasi-life entities remains inadequate. Medical education traditionally emphasizes prolonging life rather than addressing quality of life or the specific needs of people with disabilities. Most physicians receive little training in caring for patients with disabilities, leading to gaps in understanding and potential bias in treatment decisions.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, crisis standards of care - protocols for rationing scarce medical resources - sometimes explicitly deprioritized older adults and people with disabilities, reflecting discriminatory assumptions about their worth and potential outcomes. This egregious approach to medical ethics sparked outrage from disability advocates and highlighted the need for systemic change.

Recent policy developments aim to address these gaps. In September 2023, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services proposed updated regulations that would, for the first time in 50 years, establish specific standards for accessible medical equipment, including examination tables, scales, and diagnostic devices. This rule recognizes that physical barriers in healthcare settings create disparities for people with disabilities of all ages. The National Institutes of Health also designated people with disabilities as a population with health disparities deserving focused research attention and funding (Barkoff, 2024).

The Biology of Quasi-Life: How These Entities Function

Understanding how quasi-life entities function at the molecular level illuminates both their remarkable efficiency and their vulnerabilities - knowledge essential for developing effective treatments and preventive strategies.

Viral Replication Cycles

Viruses follow a multi-step replication cycle that exploits host cellular machinery. The process begins with attachment, when viral surface proteins bind to specific receptors on target cell membranes. This specificity explains why viruses often show strict host ranges - a virus that infects plants typically cannot infect animals, and vice versa.

After attachment comes penetration, where the virus or its genetic material enters the cell. Some viruses are engulfed by the cell membrane through endocytosis; others inject their genetic material directly. Once inside, the virus must uncoat, releasing its genetic material from protective protein shells.

The viral genome then hijacks the cellular machinery. For RNA viruses with positive-sense genomes, the RNA can be directly translated by host ribosomes into viral proteins. Negative-sense RNA viruses must first transcribe their genetic material into positive-sense RNA. DNA viruses may enter the nucleus and integrate into the host genome or remain as separate genetic elements.

Viral proteins and genetic material are then assembled into new virus particles. Finally, these new virions are released, often destroying the host cell in the process (lysis) or budding off from the cell membrane. Each step in this cycle represents a potential target for antiviral drugs, though the virus's ability to mutate and evolve resistance complicates treatment development.

RNA viruses like HIV mutate at particularly high rates - approximately one mutation per genome per replication cycle. Within a single patient, HIV exists as a "quasi-species," a swarm of closely related variants. This rapid mutation rate enables viruses to evolve drug resistance quickly, necessitating combination therapies that target multiple steps in the viral lifecycle simultaneously.

Viroid Replication Mechanisms

Viroids replicate through a fascinating process called rolling circle replication. The circular RNA is copied by host enzymes to produce long concatenated copies - essentially one long strand containing multiple viroid sequences linked together. These long strands are then cleaved by the viroid's own catalytic RNA sequences (ribozymes) into individual circular RNA molecules.

The fact that viroid RNA acts as both genetic material and enzyme - carrying out catalytic reactions - makes them particularly interesting to scientists studying the origins of life. Early life on Earth may have relied on RNA molecules serving dual roles before the evolution of separate proteins for catalytic functions. Viroids essentially represent molecular fossils, preserving this ancient RNA-based system of information storage and catalysis.

Prion Propagation: A Unique Replication Mechanism

Prion replication differs fundamentally from all other infectious agents because it involves no genetic material whatsoever. The process is entirely based on protein-protein interactions and conformational changes.

The cellular prion protein (PrP^c^) normally exists in a particular three-dimensional shape characterized by alpha-helices - spiral structures in the protein backbone. The disease-causing form (PrP^sc^) has the same amino acid sequence but folds differently, with more beta-sheets - extended, pleated structures. When PrP^sc^ encounters PrP^c^, it induces the normal protein to refold into the abnormal beta-sheet-rich conformation.

This conformational conversion is essentially an autocatalytic process - the abnormal form catalyzes production of more abnormal forms. As PrP^sc^ accumulates, it aggregates into oligomers and eventually large fibrils. These aggregates resist cellular degradation mechanisms and accumulate in tissue, particularly in the brain, where they cause cellular dysfunction and death.

The extreme stability of prions creates major challenges for decontamination. Standard autoclaving (high-pressure steam sterilization) that would destroy any biological material doesn't fully eliminate prion infectivity. Extended autoclaving at high temperatures, treatment with strong sodium hydroxide solutions, or sodium hypochlorite (bleach) at high concentrations are required to inactivate prions on surfaces and instruments. This resistance to normal sterilization procedures raises serious concerns about iatrogenic transmission through medical and surgical instruments.

Current Research and Future Directions

Research into quasi-life continues to evolve rapidly, driven by urgent public health needs and fundamental questions about the nature of life itself. Several promising areas of investigation may lead to breakthroughs in prevention and treatment.

Antiviral Drug Development

The development of antiviral agents has accelerated dramatically, driven initially by the AIDS epidemic and more recently by pandemic threats. Modern antiviral drugs target virtually every step in the viral life cycle. Entry inhibitors prevent viruses from attaching to or entering cells. Reverse transcriptase inhibitors (for retroviruses like HIV) and viral polymerase inhibitors block viral genome replication. Protease inhibitors prevent proper processing of viral proteins. Assembly and release inhibitors interfere with virus particle formation and liberation from host cells.

RNA interference (RNAi) represents a newer approach to antiviral therapy. This technique uses small RNA molecules to specifically target and degrade viral genetic material or inhibit viral gene expression. Originally developed for treating viral infections in plants, RNAi is now being explored for human applications.

The fundamental challenge remains viral evolution. Because RNA viruses mutate rapidly, single-drug therapies often fail as resistant strains emerge. This problem necessitates combination therapies, similar to the highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) used for HIV. Using multiple drugs simultaneously that target different viral processes reduces the likelihood that resistant strains will emerge.

Prion Disease Research

Despite decades of research, no effective treatments exist for prion diseases. Many compounds show promise in test tubes or laboratory animals but fail in human patients. One treatment that prolonged incubation periods in mice failed in human trials with variant CJD patients. Another promising drug tested in six human patients showed no significant increase in lifespan, though autopsy results suggested it safely reached the brain in encouraging concentrations.

Current research focuses on several strategies: preventing PrP^c^ from converting to PrP^sc^, stabilizing the normal protein conformation, enhancing clearance of misfolded proteins, and blocking the neurotoxic effects of prion aggregates. Understanding prion-like mechanisms in more common neurodegenerative diseases may lead to treatments applicable across multiple conditions.

Some researchers explore whether boosting proteostasis - the cellular systems maintaining protein quality control - could prevent or slow protein misfolding diseases. Others investigate whether immune-based approaches, despite prions' notorious ability to evade immune detection, might offer therapeutic possibilities.

Quasi-Life Systems in Biotechnology

Beyond disease, quasi-life concepts find applications in biotechnology. Research on "quasi-life self-organizing systems" has examined modified proteins that create self-organizing ensembles with enhanced properties. Studies on succinylated derivatives of interferon-gamma demonstrated that these quasi-life ensembles could protect cells from viral infection more rapidly and effectively than native interferon, suggesting potential therapeutic applications (Muronetz et al., 2011).

Understanding how quasi-life entities co-opt cellular machinery also informs efforts to design synthetic biological systems. Engineers designing minimal self-replicating systems or artificial cells draw insights from viruses and viroids - nature's minimalist replicators that accomplish reproduction with remarkably compact genetic toolkits.

Improving Outcomes for Vulnerable Populations

Research specifically addressing the heightened vulnerability of older adults and people with disabilities to quasi-life infections remains limited but growing. Studies examining why aging increases susceptibility to viral infections may reveal targets for interventions that could boost age-related immunity. Understanding the role of normal prion protein in protecting against viral infections suggests that therapies enhancing this protective function could benefit elderly individuals.

Healthcare system improvements remain critical. Better training for medical professionals on caring for patients with disabilities, development of accessible medical equipment, and elimination of discriminatory crisis standards of care all represent necessary steps. Research quantifying disparities and identifying specific barriers to care for vulnerable populations provides the evidence base for policy changes.

Vaccination strategies must account for age-related decline in immune response. Higher-dose flu vaccines specifically designed for older adults reflect this understanding. Similar approaches may benefit other vaccines protecting against quasi-life entities.

Conclusion

Quasi-life entities - viruses, viroids, and prions - occupy a fascinating biological gray zone, possessing some characteristics of living organisms while lacking others. These entities cannot reproduce independently, relying instead on hijacking the cellular machinery of truly living hosts. Despite their structural simplicity, or perhaps because of it, quasi-life forms cause devastating diseases that have shaped human history and continue to threaten global health.

The impact of quasi-life on vulnerable populations, particularly older adults and individuals with disabilities, demands urgent attention from researchers, healthcare providers, and policymakers. Age-related immune decline makes elderly individuals more susceptible to viral infections and less responsive to vaccines. Prion diseases predominantly strike older adults, and prion-like mechanisms contribute to common age-related neurodegenerative disorders. People with disabilities face compounded vulnerabilities through immunological, physiological, and social factors.

Understanding quasi-life is not merely an academic pursuit but a practical necessity for protecting public health, especially for our most vulnerable community members. As our population ages and medical advances enable more people with disabilities to live longer, fuller lives, addressing the threats posed by quasi-life entities becomes increasingly critical. This requires continued research into the basic biology of these entities, development of better treatments and prevention strategies, and systemic healthcare improvements ensuring that all individuals, regardless of age or disability status, receive appropriate, respectful, and effective care.

The study of quasi-life reminds us that nature rarely respects the tidy categories we create. At the boundary between living and non-living, these entities challenge our definitions while teaching us profound lessons about biology, evolution, and the intricate relationships between hosts and parasites. As we continue unraveling their mysteries, we move closer to protecting human health and wellbeing across all stages of life and abilities.

References

Adachi, A. (2021). Frontiers in virology: An innovative platform for integrative virus research. Frontiers in Virology, 1, 665473.

Barkoff, A. (2024). Administration for Community Living initiatives on disability accessibility. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Campbell, E. G., et al. (2021). Physicians' attitudes toward patients with disabilities. Health Affairs.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). About prion diseases. Retrieved from CDC Prions Division.

Colson, P., Raoult, D., et al. (2023). From viral democratic genomes to viral wild bunch of quasispecies. Journal of Medical Virology, 95(1), e29209.

Dalakouras, A., Dadami, E., & Wassenegger, M. (2015). Engineering viroid resistance. Viruses, 7(2), 634-646.

Devi, N., & Sharma, V. (2025). An insight into the viroid-induced immune signaling pathways in plants. Discover Plants, 8(1), 191.

Diener, T. O. (1971). Potato spindle tuber "virus": IV. A replicating, low molecular weight RNA. Virology, 45(2), 411-428.

Domingo, E., & Perales, C. (2025). A general and biomedical perspective of viral quasispecies. PMC Articles, 11874995.

Flores, R., Hernández, C., Martínez de Alba, A. E., Daròs, J. A., & Di Serio, F. (2005). Viroids and viroid host interactions. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 43, 117-139.

Goodman, J. R. (2020). An evolving crisis. New Scientist, PMC7255208.

Hainfellner, J. A., et al. (2001). Aging, the brain and human prion disease. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development, 123(4), 293-298.

Hammann, C., & Steger, G. (2012). Viroid-specific small RNA in plant disease. RNA Biology, 9(6), 727-732.

Jaunmuktane, Z., Mead, S., Ellis, M., Wadsworth, J. D., Nicoll, A. J., Kenny, J., ... & Collinge, J. (2015). Evidence for human transmission of amyloid-β pathology and cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Nature, 525(7568), 247-250.

Jucker, M., & Walker, L. C. (2024). The prion principle and Alzheimer's disease. Science, 385(6713), 1278-1279.

Jaunmuktane, Z., & Collinge, J. (2020). Invited review: The role of prion-like mechanisms in neurodegenerative diseases. Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology, 46(6), 522-545.

Kovalskaya, N., & Hammond, R. W. (2014). Molecular biology of viroid-host interactions and disease control strategies. Plant Science, 228, 48-60.

Lukiw, W. J., et al. (2022). SARS-CoV-2, long COVID, prion disease and neurodegeneration. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 13, 982.

Matsushita, Y., & Kawaguchi, A. (2025). Viroids, the smallest plant pathogen, suppress bacterial plant disease via epigenetic changes and RNA silencing. Plant, Cell & Environment, 48(1), 70208.

Mattson, M. P., & Magnus, T. (2006). Infectious agents and age-related neurodegenerative disorders. Ageing Research Reviews, 5(1), 1-13.

Muronetz, V. I., et al. (2011). Quasi-life self-organizing systems: Based on ensembles of succinylated derivatives of interferon-gamma. Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, 12(2), 218-224.

Nakamura, Y., et al. (2018). Prion protein protects mice from lethal infection with influenza A viruses. PLOS Pathogens, 14(5), e1007049.

Nature Publishing Group. (2024). Quasispecies theory and emerging viruses: Challenges and applications. npj Viruses, 2(1), 66.

Prusiner, S. B. (1998). Prions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 95(23), 13363-13383.

Prusiner, S. B. (2001). Neurodegenerative diseases and prions. New England Journal of Medicine, 344(20), 1516-1526.

Prusiner, S. B., et al. (2019). Alzheimer's disease is a 'double-prion disorder,' study shows. Science Translational Medicine, 11(490), eaat8148.

Riesner, D., & Gross, H. J. (2018). Viroid research and its significance for RNA technology and basic biochemistry. RNA Biology, 15(9-10), 1265-1280.

Sano, T., & Matousek, J., & Singh, R. P. (2021). Role of RNA silencing in plant-viroid interactions and in viroid pathogenesis. Frontiers in Plant Science, 12, 640328.

Science for the Public. (n.d.). Life: Quasi-life. Retrieved from Science for the Public Educational Resources.

Senatore, A., Colleluori, R., Poggiolini, I., Matteoli, G., & Meli, G. (2014). Prion protein and aging. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 2, 44.

Singh, R. P., Dilworth, A. D., & Singh, M. (2021). Viroids and satellites and their vector interactions. PMC Articles, 11512221.

Tripathi, S., Yadav, V., Balaji, P. V., & Tuteja, N. (2021). An inside look into biological miniatures: Molecular mechanisms of viroids. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(6), 2795.

Walker, L. C., & Jucker, M. (2019). Prion-like mechanisms in Alzheimer disease. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 153, 303-319.

Wassenegger, M., & Dalakouras, A. (2022). RNAi tools for controlling viroid diseases. Plant Science, 316, 111156.

Wikipedia. (2024). Prion. Retrieved December 2024.

Wikipedia. (2025). Viroid. Retrieved December 2025.

Wu, Y., Wang, X., Zhao, C., Liu, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2025). Cellular prion protein and amyloid-β oligomers in Alzheimer's disease - Are there connections? International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(5), 2097.

Insights, Analysis, and Developments

Editorial Note: As we've explored the intricate world of quasi-life, one truth emerges with clarity: the boundaries we draw between living and non-living, between simple and complex, between scientific curiosity and human impact, are far more permeable than they first appear. Viruses, viroids, and prions - these minimalist entities that exist at the very edge of what we call life - wield enormous power to shape not only biological systems but human societies. Their disproportionate impact on older adults and people with disabilities reminds us that scientific understanding must always connect to human consequences. As researchers continue probing the molecular mechanisms of these remarkable entities, as clinicians work to develop better treatments, and as policymakers strive to protect vulnerable populations, we are reminded that every advance in our understanding of quasi-life represents not just knowledge for its own sake, but hope for longer, healthier, more equitable lives for all members of our community. The questions quasi-life poses about the nature of existence, replication, and infection remain as fascinating as they are urgent - a frontier where fundamental biology meets profound human need - Disabled World (DW). Author Credentials: Ian is the founder and Editor-in-Chief of Disabled World, a leading resource for news and information on disability issues. With a global perspective shaped by years of travel and lived experience, Ian is a committed proponent of the Social Model of Disability-a transformative framework developed by disabled activists in the 1970s that emphasizes dismantling societal barriers rather than focusing solely on individual impairments. His work reflects a deep commitment to disability rights, accessibility, and social inclusion. To learn more about Ian's background, expertise, and accomplishments, visit his full biography.

Author Credentials: Ian is the founder and Editor-in-Chief of Disabled World, a leading resource for news and information on disability issues. With a global perspective shaped by years of travel and lived experience, Ian is a committed proponent of the Social Model of Disability-a transformative framework developed by disabled activists in the 1970s that emphasizes dismantling societal barriers rather than focusing solely on individual impairments. His work reflects a deep commitment to disability rights, accessibility, and social inclusion. To learn more about Ian's background, expertise, and accomplishments, visit his full biography.